It was January 2006. I was heading to Mendoza in Argentina, one of the largest wine regions on Earth. However, my goal was not to taste wine but to climb Mt. Aconcagua, the tallest peak on the American continent.

I started doing sport climbing when I was 14 and became quite good at it. However, after starting university, it was clear that I couldn’t continue on the same level as before. I began to focus on my academic career. This was when I switched from bouldering and sport climbing to alpine climbing, aiming to reach the summits of high mountains. First in the Alps, then came the Cordilleras in South America. It helped a lot when I moved to Munich in Germany for a few years, where the Alps were in my backyard.

The ever-higher regions of the mountains kept calling me. My first high-altitude mountaineering trip led me to Huyna Potosi in Bolivia. Although my overall condition was great, I knew nothing about acclimatization, high-altitude camps, etc. I had to learn it hard. As I reached the high-altitude camp, I had to turn back due to acute headache, nausea, disorientation, etc.

Although this first “expedition” could hardly be called successful, it didn’t stop me from wanting to do high mountaineering. I was back again in the Alps, climbing more and more 3000-4000m+ high peaks (Mont Blanc, Monte Rosa, etc.). Then in the summer of 2005, I visited the Chilean and Argentinian Patagonia to hike some epic places such as the Torres del Paine, the Glacier National Park, Calafate, and el Chalten. These are among the most beautiful and intense nature experiences I have ever experienced. After these hikes, I travelled to Mendoza to get my permit from the authorities. I purchased the necessary food, got my gear together, and took a public bus to Puente del Inka. My bag weighed 30+kg.

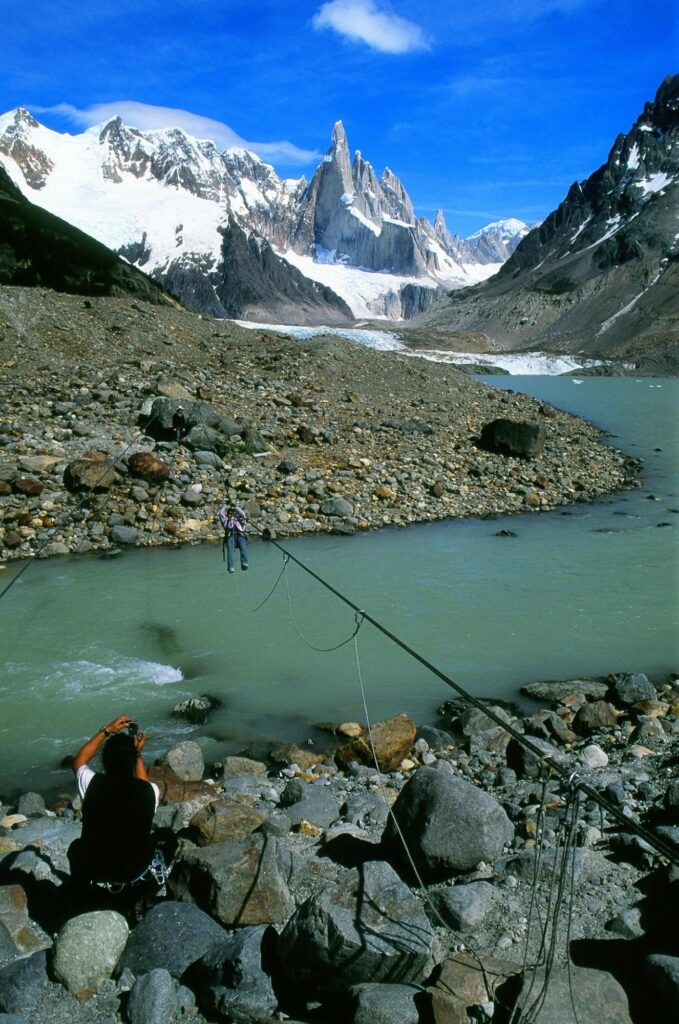

Iconic hike in Patagonia at Cerro Torre.

MY FIRST ATTEMPT AT MT. ACONCAGUA IN 2006

I started from Puente del Inka to the entrance of the National Park, where I checked in and took the well-marked path to Confluencia (3400m). Here, I spent three days acclimatizing. I walked through Horcones valley to Plaza de Mulas (4300m). This was my first real experience of a base camp (BC). In 2006, it included just a few dozen tents and domes, a bunch of guides, staff, and mountaineers. Around the camp, the landscape was breathtaking, with penitentes (a particular formation of ice and snow that look like swords standing out of the ground) as high as a human body. I started walking on snow from the BC, facing Plaza Canadá (C1) and Nido de Condores (C2). These glaciers seemed to be at arm’s length. However, my knowledge of acclimatization was not enough yet to climb higher than Nido (5580m). I felt fragile, unmotivated, and insecure. After one week, I decided to pack my stuff and leave behind this gorgeous mountain. This was 17 years ago. Back then, Mt. Aconcagua and climbing the regular route differed greatly from today. The camps were significantly smaller, with less infrastructure and much fewer people.

AS TIME PASSED BY

Then more than half a decade passed, during which I accomplished a few more 4000+ peaks, glacier travels, and ice climbs. I climbed Mount Elbrus from the North and enrolled in an ice climbing course in Chamonix. I climbed Contamine-Negri (350m AD+, 70) and other shorter routes.

After the ice climbing course, I spent some days in Chamonix. For some time, I wondered why nobody was writing a book about training theory and practice for mountaineering with a scientific approach. Back in the years, we read a lot about sport climbing from Wolfgang Güllich, who unfortunately passed away too early in a car accident. We also watched every VHS cassette about Tony Yaniero, John Long, and others, smuggled behind the Iron Curtain to Eastern Europe. Now I was looking for some proper literature on training for mountaineering.

A book that explains the basics but also opens up new doors for me to boost my knowledge and allows me to aim for more. Then I went to a bookstore in Chamonix and found just that in Training for the New Alpinism.

The Training for the New Alpinism book was a game changer for me. I started to restructure my training. It allowed me to climb new 4000+ mountains in the Alps with such lightness that I had never experienced before. The altitude didn’t make me feel weak, I didn’t get a headache, and my aerobic capacity increased. I also started to follow Uphill Athlete’s website. I regularly checked the news and videos, and I enjoyed the content. Then I saw that there is a possibility of having individualized training with UA. However, it was out of my budget before the pandemic. First, I started with self-created training plans and then with UA, the customized ones. They helped me a lot to improve my physical capacity and training adaptation.

Puente del Inca, close to the trailhead.

MT. ACONCAGUA IS TAKING ROOT IN MY MIND AGAIN IN 2021

After such a rewarding experience, my old dream of climbing Mt. Aconcagua crept back into my mind. I considered everything in the summer of 2021 and signed up for individualized training with UA. I was fortunate to be trained by one of the first European coaches of UA, Thomas Summer. It was a great experience not only on a physical level but also, if not more so, mentally and emotionally. It was the first time in my life that I had a personal coach. It was amazing to have all those great conversations and continuous feedback. My development was breathtaking, or at least I felt it so.

I booked my flight to Mendoza. What could happen, I asked myself. I was enjoying the new me. As you get closer to 50, it is incredible to experience how you can exceed the boundaries of your physical performance. Then nine weeks before my expedition started, the shit hit the fan. I was doing my last section of a hill sprint, and on the way back, I thought to run downhill in that technically very challenging section. It was a big mistake. I injured the outer tendons of my left ankle: the front was gone entirely (grade 3 tear), the middle one was almost completely gone (grade 2 tear), and the third was also affected. It was a direct result of my private life – stress. During the descent, I was not concentrating well enough on the track.

The doctor told me to cancel my expedition, and there was no chance I could do it. My physio told me, “No problem, we will fix your ankle, but how will you accomplish the necessary aerobic training?” My coach, Thomas Summer, assured me: “Step by step, weekly, we will see how your training progresses, and you can decide later how you feel.” Thomas immediately redesigned my training plan. Thanks to that, my aerobic capacity grew again after five weeks of the accident. I did not cancel my trip. Lesson learned: when you train, personal life matters are as important as your physical condition.

Leading a pitch at Contamine-Negri by the Mont Blanc du Tacul.

JANUARY 2022: ANOTHER MT. ACONCAGUA SUMMIT ATTEMPT

At the beginning of January 2022, I was again at the foot of Mt. Aconcagua. I was heading again to Confluencia solo. This time mules carried my main gear to Confluencia and the BC, Plaza de Mulas. What a change in almost a decade and a half. The colors faded, the mountain faces looked dry, and the rivers had significantly less water. I was shocked. Was this the result of climate change? I wondered.

The hikes and the acclimatization felt easy. I was never so prepared for a climb in my life. The weather forecast was perfect. I made a side trip to Plaza Francia (4200m), at the foot of the South Face (Cara Sur), a 3500m high wall with mixed climbs. It usually takes 3-4 days to the summit of Mt. Aconcagua from here, but only for those looking for epic challenges.

The next day, I hiked to Plaza de Mulas. Again, I was shocked. What I saw from the base camp vastly differed from the view 16 years ago. Almost no snow, and the most significant landmarks, the penitentes, were completely gone. No sign of them. It was a challenge to cross them earlier, and now there were just dry rocks. At the check-in of the BC, the ranger lent me a 5-liter plastic water bottle. He said there was no snow in Plaza Canadá (5080m) and Nido de Cóndores (5580m), so I must carry water from the BC. It was the tenth winter without sufficient snowfall, I learned.

After a rest day, I continued my acclimatization tours to Plaza Canadá (C1) and Nido de Condores (C2). They were also quite demanding because of the extra 8 liters of water I had to carry. Fortunately, there was a small lagoon at Nido where I could refill my bottles. I planned to spend a day at Nido and then return to BC for a rest day. However, at Nido, I learned that there was a significant change in the weather. The window of opportunity for summiting was closing. I had two days less to start for the summit, but I wasn’t there yet with my acclimatization. I had to replan.

I returned to BC as I only carried the essentials for the acclimatization tours. After a short rest, I repacked my bag and returned to Nido. I reached Nido in 5 hours at a comfortable pace. I felt satisfied with my speed. I had enough time to prepare everything for the next day – my summit push. I calculated that I even had time for 5-6 hours of sleep. Everything was set, and I went to sleep.

Arriving at Plaza de Mulas, the BC to climb Mt. Aconcagua.

After one-and-a-half hours of good sleep, I woke up. I realized that I could only breathe through my mouth. My nose was completely blocked. The air at Mt. Aconcagua is arid, and your mucous membrane is continuously irritated, so breathing can become very challenging. From this point, I couldn’t get any sleep until my alarm went off at 1:00 AM. I routinely dressed up, boiled water, got my food and fluids, packed my gear, and left my tent. It took me about 1.5 hours to prepare all this. I heard that several groups had already left for the summit.

I was exhausted from the sleepless night, but I was also motivated to reach the summit. However, my legs felt heavy and sore. My pace was slow. I should have been faster. It took me 2:45 hours to get to Berlín and altogether 3:20 hours to reach Cólera (500 m altitude difference to Nido). I continued, but my pace got even slower and slower. The sun rose, and I doubted it might be my summit day. However, I didn’t want to give up. I thought a lot about the time and resources I invested in this trip. And also my family and all the friends who supported me. I pushed ahead. With every step I took, my skepticism grew. Finally, short before Independencia at 6200m, I stopped. I looked around and was taken aback by the stunning view. I felt the rising sun’s warmth, took a muesli bar out of my pocket, and enjoyed the taste of it. After 6.5 hours of climbing, I turned back.

Why did I do it? I could give you a bunch of reasoning. However, I think mountaineering is way beyond the rational world. If you want to develop your skills, mental training is as critical as the physical one. After climbing almost 2000m within 20 hours at that altitude, I got exhausted. I was alone and needed to think about getting back safe and healthy. I calculated the time I needed to reach the summit and return solo, meaning that once you are back in your tent, you must prepare water, food, etc. However, looking back at it from a year of distance, I think the main reason for turning back in 2022 was the lack of mental strength and focus. During my preparation, I focused on my physical training. I chose to do that as I deliberately wanted to take my attention away from several problems in other fields of my life. Although my coach tried to teach me methods to clear my mind and be more focused, I didn’t take his advice seriously enough. Technically, we are pretty advanced in measuring our bodies’ preparedness, but it’s quite different with our souls. That is way harder.

ON MT. ACONCAGUA IN JANUARY 2023 - WILL I SUCCEED THIS TIME?

Off to the high camps.

On January 6, 2023, I took off from Budapest airport. This time I had a good amount of training with an excellent Mountaineering Training Group of UA, invigorating talks with UA coaches Pedro Carvalho and Thomas Summer, lots of discussions with dietitians, several hours with the physio, several weeks of sleep in a hypoxia tent, and also the unbelievable support of my daughter and my partner.

I was again in the base camp of Mt. Aconcagua at Plaza de Mulas. I saw some faces I already knew from last year.

I didn’t feel the confidence I felt the year before. My preparation was quite good, although I felt less strong than last year, and my acclimatization didn’t feel as good as in 2022 either. But the numbers showed differently. I was 20-25% faster in every section than last year. However, I faced other challenges. As I started my acclimatization tours to C1 and C2, my cooker died in C1. I had to turn back to BC and get help to repair it. I lost one day.

The news from the summit was not promising. Since January 5, there has been no summit attempt as the snow was knee-high, sometimes even hip-high. It was frigid, and with windchill, it was below minus 30. The weather window looked very short. The only possible day to reach the summit for me seemed to be January 18. I had two choices, either to ascend from Nido (5580m) as I did last year and failed, or to do it from Cólera (5970m), which is closer to the summit, but I didn’t have the necessary acclimatization for it and the nights were also much colder there. “What to do, what not to do? Let’s be rational”, I thought to myself. Mt. Aconcagua is a “big mountain.” From Nido, you must climb 1400m vertically with many kilometers to and fro in one day. Yes, but I did my bit in muscular endurance (ME) and aerobic training, and even if I didn’t feel that strong, my data showed otherwise.

The change between 2006 and 2022 is inevitable. Image by András Reith.

I decided to start from Nido. Again the alarm was off at midnight, I got myself together, and I was off. After two hours, I was in Berlín. I watched the people around me in the light of my head torch and recognized friends I knew from BC who were getting out of their tents. I was happy to see familiar faces. For him, this was the 17th Aconcagua climb. For her, it was the first time. We decided to continue together but without any obligation. It felt just right. Sometimes they were ahead of me; other times, it was me. It gave me great motivation.

As I was climbing, I recalled one of the most important pieces of advice I heard in one of the UA group sessions: “You have to trick your brain sometimes and break big objectives into reasonable pieces.”

This was precisely what I needed to do with this mountain. “Aconcagua is a big mountain,” one of the great US climbers told me last year in BC. I thought, “if you try to eat it in one piece, you will choke on it; however, if you take it in small pieces, you will even enjoy its taste.”

So, after Independencia (6300m), from the big traverse, I started to break my “big mountain” into small pieces, into 10-step pieces. One, two, three…. ten. Stop. Breathe. One, two, three… ten. Stop. Breathe. One, two, three…ten. Breathe. La Cueva – The cave. Finally sunshine. After 9:30 hours of climbing, I finally got to a place protected from the wind and almost felt warm. It is only the La Canaleta ahead of me now before the summit. One, two, three. Stop. Breathe… an additional 2 hours to go.

Looking down at the BC from Plaza Canadá (C1).

ON MT. ACONCAGUA SUMMIT

At 13:30, I was on the summit of Mt. Aconcagua (6910m a.s.l). It took me 17 years to arrive here.

After a little less than 16 hours of climbing, I reached back at Nido. I experienced precious and unique moments I had never felt elsewhere in such an environment. One of the friends who stayed there offered me water. This was the kindest thing I could think of then. He was waiting for my return with this gift. We sat down, crying. I told my story about my previous attempts, about my daughter, my partner, my family, and friends, and he shared the story of his almost 70 years. He summited four times already. This time, he came to say farewell to this “big mountain”.

You might be surprised to hear what the most moving moment during my trip was. Of course, it was an overwhelming moment to get to the highest point of the American continent and overlook all the peaks below me.

However, the most valuable experience for me was what happened after summiting when I was sitting on the big stone beside my tent, still in crampons, still wearing my goggles, drinking the water I received from this "old" Argentinian friend and listening to his last stories about the mountain that made me feel connected to all what surrounds us.

It also made me reflect on what we humans do to nature. Compared to my first trip 17 years ago, now the glaciers on the mountain are several hundred meters shorter, and the penitentes are gone, along with the stable climate and weather.

You can climb to the top without snow in one year and wear T-shirts at almost 7000m. In another year, you cannot leave Colera due to the high snow, while the hospital in Mendoza is full of frostbite patients. “You have winter conditions in summer,” one of the local guides told me. This worries me. I would like my daughter also to see all the wonders of nature.

So, for a start, as I am not sure I can trust the airline company’s website that they will offset my 4.3 metric tonne CO2 for €5-50, I have decided to calculate my trip’s carbon footprint and plant over 200 trees in Hungary.

All images belong to András Reith.

The point where I turned back in 2022 at 6200m, close to Independencia.

The summit of Mt. Aconcagua, with the drawing I got from my daughter.