Back when I was doing a lot of shorter trips to Patagonia, really fast down and back, having success, I coined the term “Daddy style.” It’s alpine style but for a family man with two kids, like myself: show up super fit, crush something, and then head home. Make the most of your pre-trip training so that you can make the most of your climbing. It’s a tactic I’ve always deployed for alpine climbing, and in the past two years I’ve applied it to harder rock climbs—to mastering the 5.13 grade.

-by Whit Magro

I’ve been climbing since I was 16: alpine rock climbing, ice climbing, going on expeditions. But when you do a lot of expeditions and focus on long routes in Yosemite and desert crack climbing, you can only take your hard rock climbing so far. As I progressed through the grades, I plateaued around 5.12.

Then I met Josh Wharton in 2008, when we went on an expedition to Pakistan to try to climb Latok I. Almost immediately, I noticed his commitment to training. I did a couple sessions with him at base camp, using a hangboard we rigged on a boulder. I saw what this focused training could do, and I took what I learned home and incorporated it into my own routine. I broke into the 5.13 range on alpine routes, big walls, and harder trad and sport climbs.

Two years ago, I fully committed to Josh’s training regimen, and I’ve really seen the gains from it. Before the winter of 2015/2016, I’d probably done 30 routes of 5.13 or harder. Then last year alone—in 2017, after training all winter—I did 30 routes harder than 5.13. I was putting them down all over the place that season. Not just in the backyard, but all over the country and in Canada.

When it comes to the program, Josh has done his homework. He’s a full-time climber, so he researches what’s out there, puts what he learns into practice in his own climbing, and hones it through trial and error. Then he shares what works in the form of an organized, effective progression that spans multiple months. He makes it easy for me. Plus, it helps that he has a vested interest in keeping me trained up for climbing trips we go on together. He wants me ready to send. And I want to be ready to send, too.

The program kicks off with a series of eight fingerboard sessions, then six to eight sessions of campus boarding. Leading up to the trip you do power-endurance workouts, like 4x4s in the bouldering cave at the gym, then you do a final series of max hangs, which is the recruitment phase. That brings the whole three-month program to a peak so that you come into the trip feeling fit and strong.

If you do it like he lays it out, you can keep track of your progress. That’s the most valuable thing you can do in the training, and that’s what Josh stresses in his program—keeping track of your personal records and how you’re performing. Your goal is to beat what you did in the previous session, which means you may have to make sacrifices, like giving up a day of climbing because you don’t want to be tired for the training and fail to improve. Instead of doing the same after-work rock session you’ve done a hundred times, you go and do something that’s harder. Maybe it’s not as fun, but it’s more challenging, and you can get a lot out of 2 hours—sometimes more than you would going climbing for a whole day.

If you keep track of everything—your times, your weights from your hangs, the holds you hit on the campus board—you can see the improvement, down to the second or down to whether you touched a hold or latched it. Sometimes it’s only half a move that you gain, but if you notice that, you’re psyched. “I got better! I did half a move more!” The progress is super motivating, and I enjoy nerding out with the data. If you don’t write it all down, you don’t know what you need to work on. You’re shooting into the dark.

Overall, the training has really improved my finger strength and power-endurance—my ability to hold on to the little holds and hold on to more of them in a row. But it has also given me a mental advantage: now I know what I need for rest and recovery and how to bring myself to beat my personal best. I’m practicing preparation every time I go into a training session, because I’m always trying to do better. This mindset transfers over to working on a rock climbing project, where you’re always thinking about how to gain one more slight advantage to make the climb a little easier.

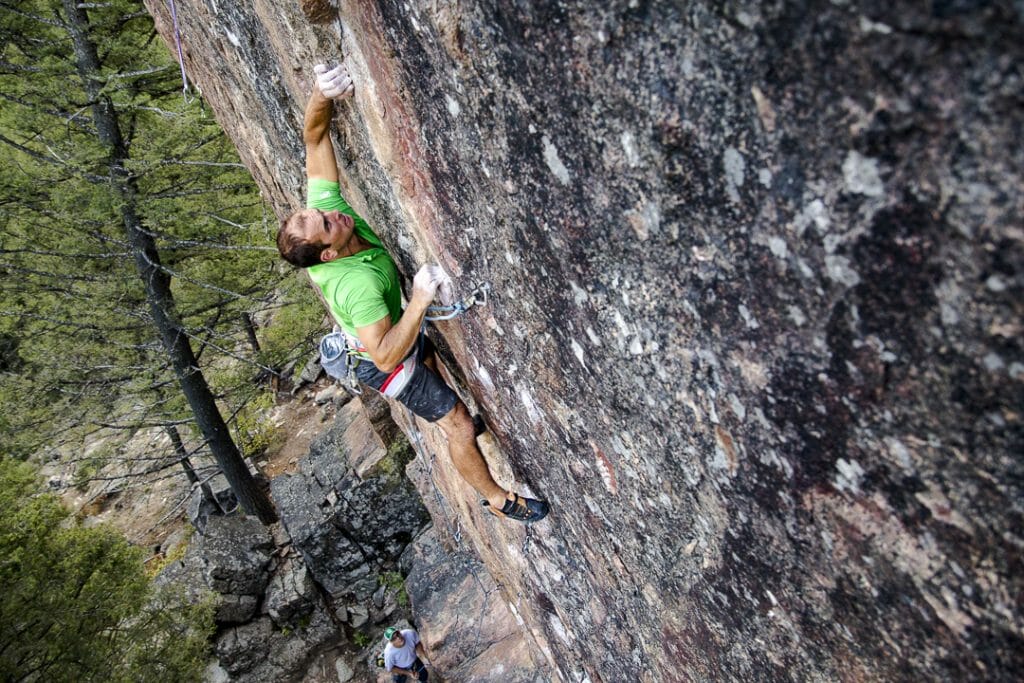

One of my goals going into 2017 was to put together a new route I’d established on a thousand-foot wall in the Clarks Fork of the Yellowstone in Wyoming. I started this thing in the spring of 2016 and worked on it all through 2016 and 2017, alongside Greg Collins, Brady Johnston, and many other helpers over the months. It’s a mixed climb, with gear and bolts, so it took a lot just to clean the route and install the hardware for the first ascent.

The Clarks Fork area has an alpine feel, almost like a mini Black Canyon. I’ve been climbing there for 20 years, putting up new routes. We just never talk about it. It’s our Montana mantra. But I’m making an exception with this route, which is so mega and took so much time and effort that I want people to do it.

I knew the climbing would be really hard for me, so I trained for it all winter. Then last November I finally sent the entire route. Yellow Wolf might be Wyoming’s most difficult multipitch climb, with a pitch of 5.14-/13+ and an additional four pitches of 5.13, plus five pitches of 5.11 and below; it’s stacked. The crux pitch—this thin, technical 45-meter granite slab, sustained, but with a few shakes; think “traddy”—is definitely one of the harder pitches I’ve ever sent. I’ve done a few pitches at 5.13+ now, maybe six or so, and it’s on the harder side of those. I think it could be 5.14-, but I want confirmation before calling it that.

Just two days after Yellow Wolf went down, I sent a 5.13+ sport climbing project—my 25th pitch above 5.13a in 2017. That whole week was a culmination of all the training, all the preparation. It’s worth the little sacrifices. You have to love climbing to want to get better at it.

You May Also Be Interested In:

- Josh Wharton’s 4-Week Beginner to Intermediate Rock Climbing Training Plan

- Josh Wharton’s 8-Week Intermediate to Advanced Rock Climbing Training Plan

- Free Climbing El Cap from the Ground Up

- Rock Climbing Drills

- Rock Climbing Training: ARCing