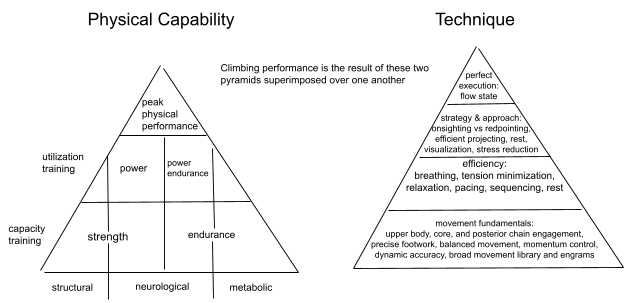

The secret to improvement as a climber is to understand how to best balance improving your movement skills while training strength, power, and endurance.

Training for rock climbing can often feel complex and challenging. Endurance, strength, and flexibility are all vital components in order to conquer the physically demanding and technique-intensive nature of this sport. From scaling steep cliffs to navigating precarious holds, rock climbing requires a unique combination of mental focus and physical prowess. With each ascent, climbers constantly refine their skills and push their limits, unlocking new levels of accomplishment and personal growth.

Training for rock climbing comes down to familiar concepts: consistent and gradual base work develops and trains your body to the specific demands of rock climbing. Invoking gradualness and modulation is especially important for athletes over 30 who are at greater risk of overuse injury. On top of healthy connective tissue and whole-body strength, we re-orient training towards muscular endurance that, while feeling tough, these powerful contractions of your muscles and focused loads on your connective tissues will lead to rapid gains in performance. It is important to continue to train endurance at a lower frequency to maintain the bodies’ capacity to manage the metabolic demands of climbing. The last period will be power or your more sport/route specific period. This is the period during which you start projecting. Teaching your body slowly how to do what you want it to do.

Sounds complicated, but for the student of Uphill Athlete it will all be familiar. Coupled with principles of consistency and adequate rest, recovery, and nutrition you cantrain sustainably and achieve high-level performances while staying injury-free. This model holds up whether the angle of the rock climb is a low-angle slab or goes well beyond vertical. Our approach will help you build the specific climbing skills, along with the strength and endurance you need for those creative, fun, and technically challenging rock climbing movements that bring us so much joy in our sport. Note that due to the dominance of technical skills and strength of climbing on rock, the heart rate zones that are so useful in endurance sports simply don’t apply for rock climbing training. More on that later.

We’re going to start by helping you form a mental model for how effective training for rock climbing works. To do this, we need to oversimplify reality.

There are several overarching training principles that must be incorporated into the optimal mixture of skills training, endurance training, and strength training which support efficient, safe, lifelong joy in climbing.

FUNDAMENTAL PRINCIPLES OF TRAINING FOR ROCK CLIMBING

We will break these principles into:

- Climbing Skills

- Endurance Capacity

- Maximum Strength/Power Capacity

- Mental Training

CLIMBING SKILLS

ENDURANCE CAPACITY

MUSCULAR ENDURANCE

MAXIMUM STRENGTH

Climbers often use the equally-correct term: Power

MENTAL TRAINING

This is where it is all tied together and is the final stage of training, but truthfully, this capacity is developed throughout one’s life, not only on the rock. A climber who has mastered this stage has the mental resilience to climb many pitches while occasionally climbing near-limit crux moves while in a flow state.

SKILL ACQUISITION/HABIT FORMATION IN ROCK CLIMBING

The first foundational concept of training for rock climbing is the accumulation of a high volume of climbing-specific movement skills. Especially for climbers early in their climbing journey, this skills training for rock climbing will also result in broad increases in your vocabulary of movement, endurance, and strength.

Skill acquisition sessions in rock climbing must be done when you are well-rested.

This is true whether these are done as stand-alone sessions or combined with other training. Do this training early in the workout before you get fatigued. This is because the first physical quality to deteriorate with fatigue is fine motor skills. Climbing combines coarse (a simple movement like pull-ups) and fine motor skills (like holding and moving through a tenuous position on the rock where no single joint can move more than a few degrees). Watch the climbers in your gym and see if you observe how fine motor skills combined with high strength separate the best from the rest.

Consistent improvement and refinement of climbing movements require an awareness of how robustly a specific skill holds up under duress. Whether it be a max strength movement such as a one-arm pull-up or the precise core stability required to dance up a sustained, foot-intensive face climb. Considering how reliable and durable a personal skill is on this spectrum provides a framework for identifying climbing-specific functional movement patterns that can be isolated and trained to robustness. Again this is because….The first physical quality to deteriorate with fatigue is fine motor control.

For a skill to be robust, it must become instinctual to the body because achieving flow in your climbing has its roots in a your ability to perform from instincts, not thought.

Instinctive response takes place in the motor cortex without conscious thought. Think about the simple skill of walking. You don’t need to expend any conscious thought to walk and talk at the same time and is a much quicker and more reliable tool than the slower deliberation of the conscious mind which takes place in the frontal cortex. Think of mental long division. Chances are you would need a great deal of conscious thought for this task.

Ever notice how people stop talking when they get to the crux of a climb? However, acquiring robust skills requires a kernel-conscious awareness where you objectively observe how your own internal state aids or hinders performance. Cultivating this observer state is the foundation for identifying personal strengths, weaknesses, and refinement of movement patterns.

FOUR STAGES OF CONSCIOUS HABIT FORMATION IN ROCK CLIMBING

This process is exemplified in the four stages of conscious habit formation. These four stages are:

1) Unconsciously unskilled

You have low skill in some areas and low awareness of this lack of skill.

2) Consciously unskilled

You have low skills but are aware of the fact and consciously working to acquire good skills.

3) Consciously skilled

You have high(er) skills and are working consciously to improve them.

4) Unconsciously skilled

You have high skills and do not need to think about them any longer because they are ingrained. This is the stage of mastery.

The progression through these stages seldom aligns with a particular period in the training cycle. Instead, it serves as a framework for self-reflection and assessment of the quality and effectiveness of your training and skill acquisition over many seasons and years.

TRAINING REGIMES FOR SKILL ACQUISITION IN ROCK CLIMBING

Identifying new skills and developing efficient movement patterns and habits is crucial for progress in climbing. The good news is that we can use our training for power, endurance and durability to reinforce efficient movement patterns.

With this in mind, we now see that base training is used to both increase general climbing readiness and add durability to encounters with limit movements and sections of climbs. Keep in mind that for base work to be most effective, it must be shaped and informed by practicing limit movements.

A limit movement is our term for a climbing move that can consistently be climbed when fresh but feels right at our limit and can’t be done when we’re tired or distracted. We’ll use this term later on in your self-assessment.

Simply going to the gym and climbing mindlessly for an hour as if running on the treadmill will not lead to long-term improvements in climbing. Since limit movements magnify both good and faulty movement patterns, they serve as an essential means of study to identify the skills, strengths, and capacities that are then targeted and trained to robustness.

If you practice a move repeatedly wrong, you will simply get better at doing it wrong. This is because the instinctive mind doesn’t distinguish between ‘right’ and ‘wrong’. So we must observe and replace preconditioned, inefficient movement patterns with more efficient ones. Thus, it is necessary to strive for perfection in movement in all circumstances.

All adaptations, whether metabolic, structural, or otherwise, are slow to occur. Without going too deep into neurophysiology, basically, myelination produces faster and stronger nerve impulses of movement-specific neural pathways and their associated mental states. Succinctly, ‘nerves that fire together, wire together.’ So take heed that perfect practice makes perfect, and there is no way around this fundamental feature of human physiology.

WORK CAPACITY/ENDURANCE IN ROCK CLIMBING

The essential point is that by training you’re trying to take limit movements and make them into base movements over the weeks, seasons, and years. Keep in mind that endurance is not limited to long-duration efforts. If one month ago you could only do 1 repetition of a particular movement, and now you can reliably do 5 reps, your endurance has increased massively for the movement.

A general level of fitness and readiness for training form the backdrop from which all subsequent gains occur. Without this, the opportunity to exist in the proper physiological state that would allow such gains will not be present, and progress will be slow. As such, a baseline of aerobic fitness and metabolic efficiency must be present while other climbing-specific adaptations are encouraged.

Let’s borrow some general training concepts. For an athlete with a short aerobic training history, this can take the form of aerobic base training through increasing metabolic efficiency by working on general fitness through running, hiking, and other longer-duration efforts. For beginner and intermediate climbers this general fitness can drastically improve body composition. However, running and hiking in itself will not make you better at rock climbing. So structuring climbing-specific training that addresses deficits in the specific skills, strength, and endurance of climbing while simultaneously adding new and updated skills continuously onto a reliable base produces the structural and metabolic robustness that sets the stage for for consistent improvement.

A consistent base of climbing movement volume must be tailored to the climber’s level and their goals, and this level must be increased throughout the seasons and years. This is because what would be considered an advanced movement for a climber just breaking into 5.9 would be considered a very basic movement for someone who climbs 5.12. This pattern holds over the entire spectrum of climbing grades—someone who climbs 5.15 will consider 5.12 terrain very basic. Climb long enough and I guarantee that someone will come along and use your project as their warm up to prove this point for me.

At the other end of the hierarchy of skills are those at the edge of a climber’s ability. There are countless skills and abilities that can be lumped into this group. And regardless of the level of the climber, there are specific skills and capacities that must be identified and then trained to the level of instinct for each climber to progress. For each individual, identifying these ‘edge abilities’ provide the backdrop for which the climber’s current level is compared against their goal routes.

At this point, we need to integrate two concepts that have been artificially segregated.

Part of our philosophy is developing movement skills and enhancing the climber's metabolism to support endurance by training these together.

By simultaneously increasing endurance capacity and refining specific skills, climbers become more resilient, versatile, and proficient in achieving their climbing goals.

We will give two examples to illustrate the spectrum that an individual climber may be present with and then highlight a path forward for each.

Example 1: The climber has a long history of rock climbing on many different types of rock. They have climbed at a relatively consistent grade for many years but have plateaued and are looking to increase their ability.

In example 1, the path forward is to identify the key limiters that are contributing to the plateau and training more efficient solutions when confronting ‘edge abilities’ while also dialing the specific patterns that support these edge abilities during easier, higher volume climbing.

Example 2: The climber is relatively new to climbing but has enjoyed some highlights and successes that have made him or her want to understand what it will take to increase their level of climbing consistently.

In example 2, being relatively new to climbing, it is important to establish habits of movement that will be essential for higher grades. This is done by increasing strength and work capacity in functional movements and emphasizing skill acquisition during all climbing activities. Perfect practice makes perfect execution.

The main difference between these two examples is while the challenge for the climber in example 2 is to learn and apply new skills, the climber in example 1, must unlearn and replace old skills with more effective ways of moving on rock, which is actually harder than learning new skills for the first time. Whether you are closer to the example of climber 1, or climber 2, the path forward becomes clear when you identify skills that you can train to robustness by the process of conscious habit formation outlined above.

New skills must be trained both in isolation and in concert with more robust and well-developed skills. Base movements and skills run the spectrum from one-repetition maximum strength, such as max dead-hangs to long-duration climbing intervals where a specific skill is trained during the act of climbing.

These two ends of the spectrum and the regimes that fall in between are outlined below. These various training regimes can be tailored to the specific situation of each climber.

ROCK CLIMBING WORKOUT TYPES

AEROBIC BASE

As we have said many times before, a well-functioning aerobic system allows the body to work efficiently and recover both during training and between training days. For the activity of rock climbing, you can do Z1 and Z2 runs, hikes, and climbs.

Continuous Climbing Intervals (AKA, “ARCing”)

Long-duration and high-volume climbing provide a number of beneficial structural and metabolic adaptations. ARCing was the term coined by the Anderson Brothers in their excellent, albeit older, book Training for Rock Climbing. Whether in local muscles such as the forearms or systemically in terms of whole body work capacity, long-duration intervals are a fantastic time to gain general endurance and drill robust skills and movement patterns. Over climbing times lasting several minutes to a half-hour or more, long-duration climbing must be at an intensity level specific to each individual climber for the proper training effect to occur. A good rule of thumb for this level is 30-40% of the climber’s maximum intensity.

TRAINING REGIMES INTENSITY LEVEL GUIDELINES (WITH EXAMPLES)

Here are some guidelines for finding the proper intensity level for this activity – the ability to maintain a low-level but continuous pump in the forearms; the ability to stop and self-correct faulty movement patterns; the ability to stop and rest on the climbing surface to properly manage pump and fatigue to fulfill the predetermined duration of climbing time.

Work Capacity: Medium duration intervals of climbing times between three to upwards of seven minutes are best tailored to the difficulty of the non-crux sections of the climber’s goal routes, but these times are only a rough guideline. For instance, if your goal route is a multi-pitch 5.13 with a V6 boulder crux interspersed with 5.11+/12- sections, the climber would benefit greatly from the ability to climb the non-crux sections and pitches in a steady state.

Therefore, the climber should focus on the ability to make 5.11+/12- a steady state of intensity they are confident they can navigate in a moderately fatigued state. Here, work rest intervals that start at 1:3 climbing to rest ratio, and then over the weeks and months, decreasing this ratio to 1:<1 moves the climber to a higher steady state. Keep in mind here that when the climber can climb for a longer duration than they find the necessity to rest, this level of climbing (in this case, 5.11+/12-) can be incorporated into their long-duration intervals as outlined in the previous section.

Power Endurance: Climbing intensities at levels encountered at the cruxes of specific projects form the basis for the climber’s power endurance training. In the case of the example above, the ability to climb V6 reliably would be a useful target. Several different regimes can be implemented to support the climber’s ability to climb reliably and efficiently in crux terrain.

However, the common thread is that the climber is amassing an increasing quantity of boulder problems of a similar style, and level to the crux difficulty of their goal climb. Outlined below are several regimes that target power endurance.

Bouldering Circuits: Doing a circuit of boulder problems that includes attempts and/or completion of three or four different climbs that are at or slightly above crux difficulty, along with twice as many easier climbs.

4x4s: Pick four boulder problems that are around your flash level, and involve 5 to 15 moves. Preferably pick problems you have done in the past, emphasizing physical moves and no inconsistent beta. Err on the easy side in workout #1 if you’re unsure of how hard the problems should be. Complete each problem in rapid succession without stopping. Rest for two minutes. This is one set. Repeat four sets.

Medium Duration Climbing Intervals: Pick a climb, a grade or so below your flash level. Climb the route and note how long it took you to complete it. Rest for an equal amount of time to climbing time. Repeat this four to seven times. End the workout when technique suffers.

A more advanced version of this work-to-rest regime is best applied to simulate the work/rest requirements of project routes. For instance, if you know that a project requires you to be climbing continuously for three minutes between rest positions, and you can recover at the rest for a maximum of two minutes. Then, simulating this work/rest time while training will prove advantageous for conditioning your body’s readiness for your project.

Strength and Power: A large variety of specific strength and power exercises lead to gains in climbing ability. However, it must be noted here that just because these are easy to measure and see progress, gains in these areas are only part of a well-rounded training program for rock climbing. Before we give example exercises, it must be emphasized that climbing volume gained through the various methods outlined above will improve climbing ability consistently over time.

To optimize strength and power training, adopting a "less is more" approach that focuses on specific weaknesses and deficits enables climbers to quickly apply—and see—the gains from this training to their climbing movements.

Rather than outline specific training regimes in detail, we will highlight the training benefits of each so that they can be implemented at the right time in the training cycle and only give a brief example routine.

And remember: Endurance and power don’t mix.

Endurance and Power Don’t Mix (in the Same Workout)

Limit bouldering: Proper limit bouldering training involves climbing sequences of moves at max or near-max difficulty. Sequences can be as little as one or two moves but must be right on the edge of a climber’s ability. Limit moves are tried many times during a session with ample rest time and personal reflection on improving the movement quality for the next attempt.

A proper limit boulder problem can require many sessions to complete. Because of the difficult nature of the individual moves, it is important to discontinue the session when movement quality degrades. To continue to unsuccessfully attempt limit moves to the point of exhaustion causes the body to learn the movements improperly and will actually make success less likely in subsequent sessions on the same problem. There is no upper limit on rest times between attempts, but a minimum of two minutes is usually sufficient.

Pick six boulder problems at, or above your current limit. Choose problems of varying angles that target your weaknesses. Aim for a 30% to 70% success rate in problem completion. Attempt problem one for six minutes, which should be roughly three tries. Focus on max effort, and quality attempts. Rest for 6 minutes, and repeat for all six problems. If you complete a problem on the first try, remove that problem from your next session, and add a new problem.

Campusing: Campusing, by definition, is climbing without the use of the feet and legs. It is a useful exercise for improvement in dynamic, powerful movements. The rapid and strenuous nature of campusing places high loads on the body and causes the nervous system to be maximally recruited. This can be beneficial for training the body to generate speedy movements efficiently. A proper campus training session is structured similarly to a limit bouldering session, where attempts at maximal efforts are separated by ample rest times, and quality is emphasized over quantity.

Here is an example of campus board routine: On two-minute rests, work up to max ladder attempts on the largest rungs, switching lead hand with each rep. Focus on quality attempts and giving maximum effort. Stop at the end of 30 minutes or approximately 14 reps.

Example:

Lead Left (LL) 1-3-5

Lead Right (LR) 1-3-5

LL 1-3.5-6

LR 1-3.5-6

LL 1-4-6

LR 1-4-6

LL 1-4-6.5

LR 1-4-6.6

LL 1-4-7 (fail to stick 7)

LR 1-4-7 (fail to stick 7)

LL 1-4-7 (success! PR!)

LR 1-4-7 (success! PR!)

LL 1-5-7.5 (fail, goal for next workout)

LR 1-5-7.5 (fail, goal for next workout)

Workout Progression: As you begin to plateau (i.e., get the same PR in two consecutive workouts, for instance), drop down to the medium-sized rungs. Do two workouts at this rung size, aiming to equal your PR on the larger rungs. After the two workouts on the medium rungs, return to the large rungs, aiming to beat your previous PR.

Hang Boarding: In short, hang boarding improves finger, hand, and forearm strength and, when done properly, is excellent for injury prevention. Keep in mind that strengthening of the structures of the hand is very slow. Because of this, consistent loading over weeks, months, years, and decades accumulate to make the hand capable of sustaining very high loads.

There are a million and one hang board routines out there, but most fall into three basic categories:

- Maximum hangs

- Repeaters

- Long-duration hangs.

Maximum hangs: This regime usually involves hanging from the smallest or poorest hold that a climber is capable of for periods of ten seconds or less. Often weight is added to the body to stay within this time period. As a guideline, once a climber can hang a particular hold with 50 pounds added to their body weight, they should use a smaller hold.

Here is an example of a max hang routine: Complete a pyramid of 6, 6-second hangs separated by 2.5-minute rests. The first hang should feel easy, and you should barely complete, or fail, on the final hang while maintaining proper form. If you successfully complete all 6 hangs, add 5 lbs per rep in the next workout.

Hang board repeaters: There are a variety of repeater protocols that target various metabolic pathways of the forearm muscles to a greater or lesser degree depending on the hang-to-rest period used.

As a guideline remember that a shorter duration of rest trains endurance, whereas a longer rest duration trains strength.

There is no ‘perfect’ hang-to-rest ratio, so choosing the best one for you involves experimentation and reflection on the kinds of hanging durations that are found on your goal climbs.

Here is an example hang board repeater protocol of seven seconds hang time, three seconds rest: Choose five holds on your fingerboard. If your goal route or climbing trip involves mostly pockets, crimps, or pinches, you should give special emphasis to that grip type.

Keep track of the date, workout number, your weight, room temperature, the amount of weight you add or subtract from your body weight, and the length of each hang. This is critical, not just for this training cycle, but also for future cycles, as you seek to create baselines for finger strength and create a clear path to improvement.

This training log is an excellent form for this exact purpose – Hang for 7 seconds, release for 3 seconds, and repeat 7 times on the first grip. Rest for 3 minutes. Move onto the next grip and repeat 7 seconds on, 3 seconds off, times 7. Rest for 3 minutes, and continue on through all grip positions in the same way. This is one set.

On the second set, add 10 pounds, and do 6 reps of 7 seconds on, 3 seconds off, followed by 3’ rest.

On the third set, add another 10 pounds, and do 5 reps of 7 seconds on, 3 seconds off, followed by 3 minutes rest.

These workouts are also available in video format in our training plans for rock climbing.

It will take a workout or two to get the weights right. On some holds, you will likely need to take weight off using a harness and pulley system. On some holds, you will likely need to add weight by clipping weight onto your harness. With the correct weight, the first set should feel relatively easy, and the last set should feel like a battle with failure on the 3rd or 4th rep.

When you complete 3 sets successively on a particular grip, add 5 pounds to that grip on each set during the next workout.

Long-duration repeaters: As compared to the max hangs outlined earlier, long-duration repeaters are at the other end of the strength-endurance spectrum and are basically endurance exercises. They are best used if you do not have access to rock climbing or a gym. Keep in mind that actual climbing is a much more effective endurance exercise.

Here is an example protocol: Choose a large edge alternate between half crimp (no thumb lock) and open-hand.

Starting at Level 1, hang for 30 secs, then rest for 30 secs. Do 4 hangs per set and up to 5 sets per level. Rest 1 min between sets.

Aim for 5 sets per level. Use body weight or a pulley system to reduce weight.

Advance a level when you can complete 5 sets of a current level.

.

Level…Hang/Rest (Sec)

1 … 30/30

2 … 30/15

3 … 60/30

4 … 60/15

PULLING EXERCISES

As rock climbing requires pulling the body up the wall, a climber can benefit from various pulling exercises. Pull-ups are the most obvious example of exercises that translate well to rock climbing. But simply doing 100s of pull-ups a day will do little to increase climbing ability, and can lead to overuse injuries in the elbows and shoulders.

A better method is to do weighted pull-ups or one-arm pull-ups in low rep ranges. Usually, doing this once or twice a week, along with other climbing-specific training, is sufficient to increase strength and keep the climber’s elbows and shoulders healthy.

Here is an example of a weighted pull-up routine which can be found in Training for the New Alpinism:

SPECIAL STRENGTH PROGRAM USED FOR PULL-UPS

Pull-ups are the king of the upper body exercises. While climbers can debate the applicability of pull-ups to hard climbing, there is no doubt that they’re great for general strength training. They involve almost all of the body’s muscle groups from the waist up.

The program to follow for making gains in pull-ups is simple and well-tested. It has been used by many people who were either weak in pull-up strength or had reached a plateau in strength or endurance. All of them made dramatic improvements after following this plan for eight weeks. And they all did this without increasing their body weight. It can be adapted to movements other than pull-ups with some creativity. To break through a strength plateau in a specific climbing move, replicate the moves, use resistance training, and stick to the same schedule.

It works, and it is always fun to see fast progress. This routine has turned fourteen-year-old girls with noodles for arms into pull-up machines.

Do this workout twice a week.

Take at least three minutes rest between sets.

Lower slowly for five seconds on the last rep of each set.

Before starting, do a ten-minute warm-up for your pulling muscles; use an assisted pull-up or rowing machine.

Do this religiously for eight weeks!

This seems so simple—how can it work? The catch is that you must constantly adjust the load by adding weight (usually wearing a weight belt) to the point that you can only do the required reps. If the workout calls for three sets of two reps, you need to hang enough weight off yourself to only do two reps.

By doing this workout in a semi-circuit fashion, you can move from one exercise to the next after a short break of thirty seconds to a minute. Alternating muscle groups like this should allow you three to five minutes before repeating the same exercise while also compressing the time needed to complete the workout. The correct amount of recovery time between exercises is important for getting the full benefits of Max Strength.

Take as much rest as you feel you need to give your best effort on each set. With too little rest between sets of the same exercise, you risk insufficient recovery and hence the loss of the maximal muscle fiber recruitment aspect that is necessary to this type of training. While our example exercises are simple, they work the major climbing muscles and will effectively prepare you for the conversion to the Muscular Endurance phase, which comes next.

CORE TRAINING FOR ROCK CLIMBING

For our purposes, we define ‘the core’ as everything that is not arms, legs, and head. A solid and durable core is the foundation of all strength, endurance, and athletic ability. Training the core for the demands placed on it by rock climbing involves general core stability while the climber rotates, extends, contracts, or resists rotation. Challenging core stability in various positions and orientations should be the goal of all core work. Simply doing crunches may give you a six-pack, but does little to address the specific demands put on the core during climbing, or any other athletic activity for that matter. Check out our at-home strength endurance and core training program.

TAPERING

The nature of rock climbing activity is such that at specific periods of time, it is necessary to reduce the volume and/or the intensity of the climbing to facilitate a peak in performance. But unlike a distance runner, for instance, who has their race on a set date at some period in the future, climbers must often be ready to perform and do their best in a short time window because of weather and other uncontrollable variables.

As such, there are various ways to taper depending on the situation. Proper tapering can involve a drop in volume of up to 50% in a couple of weeks leading up to a climbing trip, for instance, or a deliberate reduction in training volume two or three days before attempting a goal route or project. Determining how much and how long to taper depends on the situation on the horizon. As a guideline, though, a proper taper should leave the athlete with an abundance of energy above and beyond what they regularly experience, and overflowing motivation to participate in their event when the time comes.

DIET AND NUTRITION

Proper diet and nutrition are the basis for good performance in all physical endeavors. Being adequately fueled for rock climbing varies greatly depending on the demands of the climbing day. An intense big wall free climb, for instance, usually requires much more energy than a day out bouldering. For the former, refueling between pitches with bars and gels can deliver the energy necessary to working muscles. There is a significantly reduced energy demand for the latter, so food choice and timing are less critical.

In general, a climber will want to choose easily digestible foods while out climbing and refuel adequately when the day is done.

In summary, have sufficient fuel on board for the demands of the day, and refuel adequately when the climbing is over.

MENTAL TRAINING

A comprehensive analysis of the mental training that aids high performance goes far beyond what can be explained here. However, there are several different practices and methods of analysis that, if used regularly, can be instrumental in aiding climbing performance.

The basis for all these practices and methods harkens back to the four stages of conscious habit formation, outlined at the beginning of this article. In that, it is only by bringing your mental and emotional states into conscious awareness that they can be either supported or replaced with more effective states of being.

Here are a few mental exercises that you can practice and apply to rock climbing performance.

Visualization of success: The human mind is an interpenetrating web of conditioned states arising from life experience, evolutionary heritage, and other less widely understood factors. Our web of conditioned states can work for or against us in climbing and in our daily pursuits. For our purposes, it is important to note here that to facilitate the outcome you want over the outcome you do not, you can increase the likelihood by visualizing yourself attaining the desired outcome.

The key here is to visualize success as vividly as possible, as many times as necessary, and to update your visualization with new, better information whenever possible.

For example, picture the crux section of your goal climb, and visualize yourself climbing it successfully. Pay attention to how the visualization affects your emotions. Do you feel: Excited? Nervous? Calm? Fearful? Cautious? Confident? Then visualize again with the most optimal emotional state possible facilitating the desired outcome. Do this many times until you feel that you know as many of the factors as possible that affect the outcome, and you successfully navigate them coolly and confidently. Whether you have a fear of falling, failure, or other, all can be reconciled by visualizing the outcome you want and avoiding focusing on the one you do not.

training summary

CONCLUSION

Climbing in all of its different flavors is a rich tapestry of successes and failures, triumphs and setbacks, that provide the opportunity for us to better know and understand ourselves and others in ways that no other activity can. Climbing is a microcosm of our daily lives—a magnifying glass under which our struggles, vulnerabilities, and weaknesses are brought into the light of day to be experienced in their true beauty, and ugliness. And it is through our witnessing and navigating the beauty and the ugliness in the act of climbing that we have the opportunity to truly know ourselves.

Train smart. Climb well.

By Steve House

I would like to acknowledge former Uphill Athlete coach Dave Thompson and Uphill Athlete rock climbing training plan author Josh Wharton for their valuable contributions to this article.

Training for Rock Climbing

Table of Contents