What is HRV?

Heart Rate Variability (HRV) is technology that claims to score our HRV and predict how long we need to recover from a given workout and when we’re ready to train again. Whether it’s an app or a program built into a watch, it is wonderful to think that one metric is all we need. But inaccurate recommendations, especially false positives, mean that this technology must be treated with deep skepticism.

For more on the purpose of monitoring HRV, and how to measure it accurately, in our comprehensive article.

We also have an updated article to share how our coaches use HRV to gain insights into our athletes’ training.

Our experience as coaches and as athletes

In this article Uphill Athlete coaching team relates their independent experiences with this technology and give you some warnings for using them to monitor your training. In short—the apps return too many false positives to be relied upon. Furthermore, there remain a number of questions that the app makers themselves seem unable to answer. For example: How do the various apps weigh the HRV signals and assign a heart rate variability normal range for a given athlete? How does heart rate variability change with age? And is one 50 year old weighted the same as another? What about female athletes? As we frequently state, training must be individualized to be effective.

This article generated some criticism from the maker of the ithlete HRV app, who asked to offer his views on our original article. In the interest of making our website a source of reliable and useful information for mountain athletes, we accepted his request. His response is printed following this article, followed up with our concluding comments.

Scott Semple's Experience

Scott Semple was one of the first coaches employed at Uphill Athlete and is a former Canadian National Champion in Master’s Ski Mountaineering Racing.

The idea of an app that could tell me when to train was exciting. I liked the convenience of one train-or-don’t-train metric. It would take away the second-guessing and keep me healthy as well. Right?

Unfortunately, it didn’t work out that way.

The HRV Apps

I started with Elite HRV (because it’s free) and then moved on to ithlete (because it’s nicer to look at). Elite HRV distinguished between sympathetic and parasympathetic biases in the central nervous system. ithlete’s Pro account gave more nuanced prescriptions with its Z-scoring.

But for what I needed—reliable daily training advice—neither was foolproof. Elite HRV recommendations didn’t seem to vary that much. ithlete often told me to train when I felt tired.

The Test

Late last year, I did a daily comparison between Elite HRV, ithlete, and an orthostatic heart rate test. The HRV apps are quick and simple, but an orthostatic heart rate test is far less convenient. It takes longer and it requires ongoing interpretation, but I’d had good results with it in the past. After variable results with the apps, I was willing to try something more cumbersome, as long as it was effective.

In particular, I wanted to look for false positives in any of the three methods. While a false negative—telling me to rest when I could train—could lead to undertraining, a false positive would be far worse. False positives—telling me to train when I should rest—would lead to overtraining. That would mean lost training time due to excessive fatigue or illness or both.

The test method I used was:

- After waking, I put my on heart rate monitor, lay down, and let my heart rate stabilize; then

- I did the 2.5-minute Elite HRV test; then

- the 55-second ithlete test; then

- the ~4-minute orthostatic test.

The orthostatic heart rate test consisted of:

- Recording my average heart rate over the first 2 minutes; then

- Standing up and recording my peak heart rate; and finally

- Recording my heart rate 1 minute after the peak.

The Results

Each day I recorded the recommendations of each test method. I added up the “votes” from the tests to come up with a total for the day. As the weeks passed, it became clear what the character of each method was:

- The orthostatic heart rate test (OSHR) was the most conservative. It regularly gave me “red lights,” indicating that I should rest. “Yellow lights” were even more common, suggesting easy recovery days.

- Elite HRV had a more mixed response, not as pessimistic as the OSHR and not as optimistic as ithlete. I like that Elite HRV distinguishes between sympathetic and parasympathetic biases in each reading.

- ithlete was the most aggressive and, therefore, the most concerning. A training readiness test should adopt a do-no-harm policy. ithlete appeared to prefer a train-as-much-as-possible policy.

Two instances in particular confirmed my suspicions about the HRV apps, one with ithlete and one with Elite HRV. In each instance, I was particularly fatigued and it was obvious that I needed to rest. In contrast, the apps recommended that I train.

ithlete

Of the two HRV apps, ithlete was definitely the more aggressive in its recommendations. It rarely gave me the red light, while the other two methods were more varied.

I did a lactate test on November 12 where my heart rate reached over 95 percent of maximum. (My max heart rate is over 200, and I reached 199 during that test.) Three days later, I was still tired, and it felt obvious that I needed a rest day. Both the orthostatic test and Elite HRV agreed.

Not only did ithlete recommend a training day on November 15, it did even worse. It suggested that my training should be high intensity.

ithlete doesn’t distinguish between biases in the central nervous system. That may explain the bad recommendation. ithlete seems to interpret sharp spikes in variability as enhanced adaptation rather than too much variability. I observed this on several occasions. It then recommends high-intensity training, the worst advice possible.

Elite HRV

Unlike ithlete, Elite HRV distinguishes between sympathetic and parasympathetic activity. Each recommendation includes a sign of sympathetic or parasympathetic bias. If Elite HRV sees a sharp spike in HRV, then parasympathetic activity is elevated, and it says it’s time to go easy.

At first, I thought that Elite HRV did a good job of avoiding false positives, but it finally gave one in December.

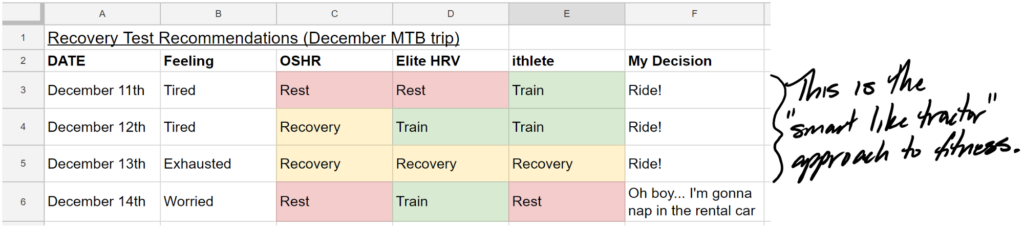

From December 11 to 13, I was on a mountain bike trip. Even before the trip started, I knew I hadn’t planned very well. I was too tired. It was a four-day trip, and we would be riding hard twice a day.

When I woke up on the fourth day, I knew that I had overdone it. I felt horrible, and I worried about getting sick. The orthostatic test and ithlete pointed to a rest day, but Elite HRV recommended training.

This is the “strong like bull, smart like tractor” approach to training: Even when you should rest, keep pushing! I went into this trip tired, and I knew it. The only readiness test that was faithful to how I felt was the orthostatic heart rate test. The other two were far too optimistic and, combined with my dumb attitude, dangerous.

In May 2019 Eric Carter, a member of the US National Skimo Team and a PhD candidate in physiology, sent us a study on HRV. Over five years, the study used 57 national-level Nordic skiers and compared their training loads with HRV readings. Their conclusion? "[We saw] no causal relationship between training load/intensity and HRV fatigue patterns."

The Orthostatic Test

Why have I assumed that the orthostatic test didn’t produce any false positives? Because whenever I felt like junk, the orthostatic test always raised red flags. It never indicated training when I was excessively fatigued. With “do no harm” as the priority, the orthostatic test was the only test that was faithful to that paradigm.

However, the orthostatic test does have a couple of disadvantages. First, the orthostatic method can take over 5 minutes while the apps are much shorter.

Second, readings are often uncertain “yellow lights,” even when I think I feel fine. That requires some careful interpretation to make the healthiest choice.

But I don’t see the longer test or the judgment calls as a disadvantage. I’d much prefer to be healthy and undertrained than fall over the edge into extreme fatigue and illness.

“It is remarkable how much long-term advantage [we]have gotten by trying to be consistently not stupid, instead of trying to be very intelligent.” -Charlie Munger, Vice Chairman of Berkshire Hathaway

Scott Johnston’s Experience

I started using HRV testing back in 2009. At that time, Polar included Own Optimizer, an HRV recovery tool, in some of their products. Own Optimizer worked moderately well, but it was eventually removed. I heard that this was because customers complained that it took too long.

Since then, I’ve tried several of the HRV apps, like ithlete, that Scott Semple discussed above. I’ve also used the recent versions of the recovery tools embedded in Garmin and Suunto watches. I’ve tried them on myself and on athletes I coach.

It was exciting to think that we could reduce the subjective judgment in coaching. Gauging recovery status is often a tough call for both athletes and coaches. Being able to use hard numbers, rather than feelings, would be a relief.

Between my own and my athletes’, I’ve looked at thousands of workouts over the past eight years. Using that data set, I’ve been able to form some general observations of HRV technology.

Observations

My conclusion aligns with Scott’s. The predictive ability of these devices is far from reliable. Roughly 30 percent of the training recommendations I’ve seen were in error. Of those, 50 percent were grossly at odds with the perception of the athlete.

My experience with ithlete was much worse than Scott’s. Using it on myself, it only once told me to rest, on a day that I was utterly spent. On every other day over a four-month period, it told me I was ready to take on the world. That just does not happen.

One young cross-country skier I coach used ithlete for a year while training at and near her limit. During that time, it warned her only twice that she might need to rest. Needless to say, those readings didn’t compare well with our observations.

One interesting anecdote that sheds some light on our skepticism came from private communications with the coach of a World Cup cross-country skier. This coach was tracking the skier’s HRV using the top-of-the-line First Beat HRV software. The data was collected at night while the skier slept and only the coach could view the data. This prevented the athlete’s anxiety from affecting the test results or performance. Overnight tests should provide the most reliability about recovery status. During one particular arduous race week, the software warned that this skier was way into the red zone of fatigue and should rest. That same day she won a World Cup race.

Uphill Athlete does some work with the US Navy SEALs. Their human performance team have tried several HRV apps on the team members. Some were too complex and cumbersome to be practical, others were simple but just not accurate enough to provide good feedback. Like us, they’ve tried and failed in their attempts to make HRV measurement an integral part of training and planning.

Read: Tapering for a Race or Event: What to do and what not to do

Why Does HRV Technology Fall Short?

The record of this technology among coaches and athletes is depressing. We all want to believe that technology holds the answer and will make the complex simple. A huge amount of peer-reviewed science supports HRV as it relates to stress. The nervous system should be the first system in the body to react to stress. So why can’t this technology live up to the promises made for it?

I have no proof of my pet theory other than 40-plus years of being an athlete and coach combined with thousands of hours watching how I and others adapt to training. Here is my take on it:

We are incredibly complex organisms. Our many systems interact in ways we don’t fully comprehend. I have no doubt that these HRV measurements are accurate. But we can’t rely upon a single metric to describe the state of the whole organism. We are too complex for such a simple model to offer reliable predictive abilities.

We are incredibly complex organisms. Our many systems interact in ways we don’t fully comprehend.

Conclusion

HRV technology seems pretty good at backcasting—looking at a past outcome and showing why it occurred. But pretty good is not good enough for what serious athletes need—reliable, daily advice on if and how hard to train in the immediate future. When it comes to that, the technology falls short.

We don’t see any benefit to using current HRV apps. In fact, telling athletes to train when they should rest is potentially harmful. We hope to get better results in the future.

References

Can your HRV number be too high?

A comparison of two methods of heart rate variability assessment at high altitude

The Accuracy of Acquiring Heart Rate Variability from Portable Devices

ithlete’s Response to Our Article

As a researcher, biomedical engineer, and creator of the first HRV app (ithlete), I’m grateful to Uphill Athlete for giving me the opportunity to reply to the recent post on cautions when using heart rate variability (HRV) as ‘the single source of truth on recovery in mountain sports.

For decades, HRV was a metric only available to medics and elite sports trainers since it required a full ECG and expert analysis. This restricted its use, but it was proven to be effective in predicting who would survive the first 24hrs following a heart attack, identifying fetal distress and even used to monitor astronauts from Yuri Gagarin to Felix Baumgartner in his jump from space.

What these situations all have in common isacutestress i.e. stress that significantly disturbs the body’s equilibrium for a short time. When faced with acute stress the body’s autonomic nervous system (ANS) is programmed to switch from parasympathetic (rest and digest) to sympathetic (fight or flight) for a short time, and then back again.

Provided that HRV is used with adequate care (i.e. same time of day, good sensor, paced breathing), it works pretty well and has been shown in hundreds of studies to be reliable for detecting acute stress from multiple sources, whether these are physical (training), mental or chemical (inc nutrition).

Problems in using HRV derive from two sources:

1. HRV readings need to be taken 5-7x per week, at the same time of day in order for the baseline statistics to be able to show when a daily change is significant.

They also need to use a good sensor (validated chest strap in good condition or a pulse sensor validated for HRV) because we are trying to measure millisecond differences i.e. 1/1000thof the pulse length. At ithlete, we also strongly disagree with taking more than one reading, because knowledge of the first reading is highly likely to affect your mental state and therefore the accuracy of any subsequent readings. We note that in the example above from Uphill Athlete ithletewas the second test performed, which is highly likely to affect the accuracy of the readings.

Finally, in fit people, HRV measures need to be done standing to eliminate an effect called parasympathetic saturation. This occurs because when lying down, the parasympathetic ‘brake’ input to the heart can be fully on, greatly reducing the ability to detect changes from day to day. When standing, the brakes come off a little, giving back the variation we are looking for.

2. Chronic stress. Acute stress is easy to detect because we have an accurate baseline from which to detect deviations. Chronic stress builds up over weeks and modifies the HRV baseline itself, making it much harder to detect. This is where there is some grey area and a risk of false positives. Additionally, different people’s bodies respond in different ways to chronic stress – with some, HRV remains low, which is easy to detect again because we can look at changes in the baseline and what’s called the coefficient of variation. With some people, HRV goes higher than normal, and can be difficult to distinguish from a well-rested state. This is when false positives are most likely to occur. The reasons for this are not very well understood, but may be related to the body producing less adrenaline, and/or becoming less sensitive to the adrenaline it does produce.

The examples given in the post mostly fit (2) above, though we quite often see problems with methodology too. When we started ithlete, there was widespread concern about whether a very short (1 min) measure taken using a phone could be accurate, but it has been validated several times, most recently in a comprehensive assessment referred to in the references below.

At ithlete, the approach we have taken is to try to identify parasympathetic dominance of chronic stress using a combination of HRV and HR in the ithlete Pro Training Guide. Whilst this is an improvement for detecting chronic fatigue, it’s not the whole answer. We are now applying artificial intelligence to combine HRV, resting heart rate, and proven subjective measures of fatigue and mood into the training guidance. We are also using what’s called the Acute:Chronic training load ratio for data imported from Garmin devices to identify when training loads are increasing rapidly and therefore the chances of illness and injury are increased. We believe bringing all of these metrics together provides a more comprehensive picture of recovery.

As a final comment on the utility of HRV, theithleteapp has recently been shown to be effective in addition to the Lake Louise score in an Armed Forces expedition to the Himalayas for detecting Acute Mountain Sickness (AMS). It has also been used by world class cyclists to detect adaptation to altitude during training camps.

Simon Wegerif Feb 7, 2019

Uphill Athlete Conclusion

We stand by our original article’s skepticism of HRV apps in the current state of the technology. Separating chronic from acute stress seems to be a major cause of the noted errors. But all athletes in training are living with chronic training stress. We acknowledge that the methodology Scott Semple employed of testing the ithlete app second may have prejudiced the reading. However, in none of our other real-world uses (many hundreds of tests) were multiple HRV readings taken—precisely because we noted that the anxiety of the athlete concerning the outcome of the HRV test had a huge effect on the test result.

The chronic vs. acute stress confusion, along with the powerful effect that the mental state of the athlete has on the test outcome, makes this a tool beyond practical application for all but a very small number of users. We continue to hope for a next generation of HRV apps that can overcome the current shortcomings. We wish Simon and his team the best of luck in dumbing this technology down for the rest of us.

2 Comments

Pingback: Making the best recovery test even better | Redline Alpine

Pingback: Making the best recovery test even better | Scott Semple