You’re two weeks out from the main event—the race, the climb, the big adventure. You’ve been training for months, stressing your body consistently and strategically to prepare yourself for the demands of your objective. Now what? For most athletes, it’s time to gradually reduce the overall volume—and in some cases intensity—of training. This is called tapering, and it will allow your body to recover from and adapt to all the work you have put in. When done correctly, it should leave you feeling fresh for the miles and elevation gain to come. The key is to invest your taper period with the same focus and energy you bring to your hardest training blocks.

Like individualized training programs, the taper period doesn’t look the same for everyone. There are a number of core concepts to consider when planning it, but don’t let them dictate exactly what you should do. Experiment. Listen to your body. Take care of yourself. In the end, the most effective approach is the one that works best for you.

Tapering vs. Sharpening

Some coaches use the words tapering and sharpening interchangeably, but there is a commonly accepted distinction between the two. Tapering involves taking your total volume down so you’re doing less and less. Sharpening entails a similar reduction in volume but with a concurrent increase in intensity. The nature of your training changes to take advantage of less fatigue from longer, low-intensity days. This is most helpful for shorter-duration endurance events with a high anaerobic component, such as trail races (especially the vertical kilometer), Nordic ski races, and skimo races that are under 2 hours.

For these events, sharpening while maintaining a measured load of high intensity helps promote glycogen utilization in the working muscles. This physiological adaptation means the athlete will be more effective at sourcing and utilizing glycogen during their event. Sessions that elicit an anaerobic effort, such as intervals in the 2-to-4-minute range, will help train this glycolytic response, helping improve an athlete’s power in the final prep before race day.

Even athletes preparing for something longer like a 50K or 50-mile ultramarathon can program a short interval workout the day before their race. This can be as simple as five minutes of 30 seconds on, 30 seconds off. The brief burst of intensity keeps the legs sharp, the mental and emotional energy high.

What Happens When You Taper?

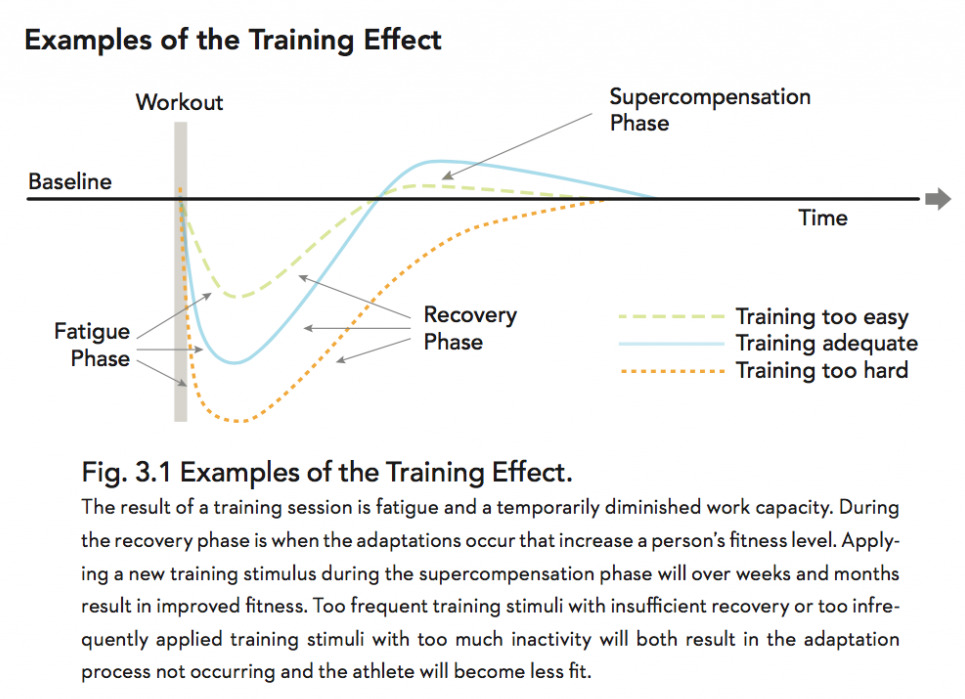

The above graph is pulled from Chapter Three of Training for the New Alpinism. A similar graph is found on page 103 of Training for the Uphill Athlete.

Training grinds you down; recovery builds you up. If you subscribe to a format of load-and-recovery—periodization—in your training, that means you break up your heavier blocks with several days to a week of reduced load in order to restore your energy and repair muscle tissue. In simplest terms, your body responds to this reduction by supercompensating for the previous stimuli. Your muscles recover and your metabolism becomes more efficient, making you better able to handle the next progressive build. It is only through recovery that you see improvements in fitness.

The taper period is a macro example of supercompensation. Where a rest day or light week between bouts of hard training allows your body to absorb the previous load, the taper is the big chunk of time where you adapt to the entirety of your training. By reducing the overall stress on your body and the inflammation in your working muscles, tapering primes you for your ultimate performance.

The taper period varies from person to person, but the goal is the same: to take all of the work you have put in and make it show up in the best possible way for your event.

Planning a Taper Period

There are a number of factors to take into account in mapping out a taper: the overall volume of your training, the duration or distance of your objective, the relative importance of the goal race or climb, and certain key metrics in TrainingPeaks.

Weigh your training load and goal and match your taper to it.

The length of your taper depends on both the size of your training base and the magnitude of your objective. As an example, take an ultrarunner who is preparing for a 100-mile trail race. She has been loading up with back-to-back volume weeks of 60-plus miles apiece. She’ll need to give her body 10–14 days of much-reduced volume in order to first absorb that ongoing training load and then build her energy back up to feel restored for the main event. Her higher-volume diet has paid into a longer performance effect.

The taper may not have to be as long for a shorter race. However, if your volume of training is just as high, consider reflecting that in your taper.

Maximize your taper for “A” races or climbs, not “B” or “C” training waypoints.

As you can imagine, tapering several times throughout a year can be disruptive for consistent training. When you have multiple events on the calendar, try ranking them in order of priority.

Take that same example of an ultrarunner training for a 100-miler. Let’s say the A race is in September. As waypoints for her training, she has also signed up for a 50K in May and a 50-miler in mid-July. Ideally, she will not taper too much for the 50K and 50-miler because the goal is to use them as B- or C-level training events. It’s OK if they don’t go well. With her expectations measured and anxiety at a minimum, she can roll into these races relaxed and with good mental energy. Then as the A-level 100-miler approaches, she can put more eggs in the tapering basket.

On the other end of the spectrum, if you signed up for a race and didn’t get the training in that you were planning, or had to take a hiatus partway through, you may feel more confident continuing to ramp up toward your goal race. If you don’t have anything to taper from, a taper will be minimally beneficial.

Use TrainingPeaks scores as a guide.

One of the many reasons we use TrainingPeaks to inform our coaching is for the useful metrics it provides in relation to an athlete’s training load and recovery. If you regularly monitor your workouts and apply TSS (Training Stress Score) numbers to them using a consistent scoring system, you will have representative Fatigue and Fitness scores—ATL (Acute Training Load) and CTL (Chronic Training Load). TrainingPeaks uses ATL and CTL to derive TSB (Training Stress Balance), also known as Form. Based on TSB, you can gauge at which point you’ll be optimally poised for a good performance. That alone can help you plan out your taper. (For more information on TrainingPeaks and the metrics discussed, visit the links above for other articles on the subject.)

5 Keys to Tapering

No matter the length or flavor of your taper period, take the following guidelines to heart. If you’re going to taper, make the most of it.

1. Relax and recover—with purpose.

Tapering is not the absence of training. It is an active pursuit—a shift in focus. Be as deliberate in tapering as you are in training: eat well; sleep well; hydrate; dedicate time to stretching, massage, and myofascial release; visualize success. Instead of just posting up on the couch with your favorite Netflix show, continue to pay attention to your body, your preparation, and your goal. (There will be time for Netflix, too.)

These days of light workouts or rest and self-care are just as important as four-hour long days. Channel any restless energy into productive recovery.

2. Make both ends of the taper gentle.

Similar to how you gradually ratchet down your volume and intensity at the beginning of the taper, reintroduce some speed the day before your objective. As mentioned above, this can take the form of a short interval workout with enough intensity to kick your legs back into gear. Even if you feel pretty flat, not exactly sharp and peppy, it should have the effect of revving your engine for the following morning.

3. Don’t fall prey to FOMO or how good you feel.

If you start your taper correctly and you’ve done the training as programmed, you will begin to feel really good. The mistake now would be to go out and do something too taxing or that too closely mimics your race effort. Do not leave your best race in training—and do not PR in any workout during the taper. When a buddy invites you on a sweet adventure five days out from the big day, just say no. Continue to save your available performance chips for the actual event.

4. Don’t replace training stress with another stress.

For the average athlete who juggles training, work, and family obligations, stress comes in many forms: physical, mental, and emotional. It is impossible to escape. But minimizing it is crucial during your taper period.

This may sound familiar: You’ve spent months channeling all this energy into training. You’ve found a way to integrate it into the rest of your busy life. It has become a form of stress relief. Then you reduce your training load and suddenly find yourself going stir-crazy with hours of newfound free time. Instead of taking this opportunity to prioritize recovery, you tack on more work. You throw yourself at home-improvement or landscaping projects and chores. Don’t blow your taper by taxing yourself physically with tasks that don’t technically fall under the umbrella of training. Recognize the impacts these other activities will have. Again, commit to the taper.

5. Stay healthy.

If you have to travel to reach your race or climbing/mountaineering objective, consider starting your taper more than two weeks out. This has as much to do with health protection as it does performance. As we all know—cough, cough—airplanes and airports are replete with disease vectors. By pulling back your training load a little early, you’ll reduce your physical stress and hopefully avoid catching something on the way to your destination. (Also think about packing in some additional immunity support.)

Especially for climbers heading to a big peak, skipping a few final training sessions won’t be a big deal if you arrive healthy. You’ll bring yourself back to form over the course of the expedition or climb.

The Taper Tantrums

When you taper, your autonomic nervous system transitions from a state of high arousal dominated by the sympathetic nervous system—fight-or-flight mode—to a state where the parasympathetic and sympathetic systems are more in balance. For some athletes, flipping the switch to rest-and-digest mode confers an emotional and mental boost that is essential for success on game day. These individuals are happy to rest on the work they did and take a week or 10 days really mellow.

More common, though, are athletes who get antsy and nervous.

That stir-crazy feeling that pushes you to do household chores rather than rest is one facet of what many dub the “taper tantrums.” You’re operating at this knife’s edge during active training. When you pull back, your body goes into damage-control mode. You miss your daily dose of endorphins, which makes you anxious and irritable. Your body feels sore, heavy, bloated, or otherwise funky. If you’ve experienced this, you know that it is easy to lose confidence in your fitness.

It’s OK to feel shitty. If you know it’s coming, you can acknowledge, accept, and even plan for it. Consider engaging in activities that you don’t have time to do during heavy training periods, as long as they won’t put you at risk for injury. The process of tapering is uncomfortable, but the ultimate outcome is the refined and performance-ready you.

To Taper or Not to Taper

A traditional taper isn’t for everyone. If the taper tantrums hit you especially hard, it may be more productive to engage in moderate training up to your event. That could take the form of an hour-long run every other day with some strides thrown in to make you feel fast. The same applies to athletes with busy lives and careers who have made a point of carving out training time in their schedules. By continuing to train, even if it’s super light and low impact, they can maintain their life balance—and sanity.

Almost every well-known coach has a story of a high-level athlete who defied physiology by doing an intense workout “too close” to race day and then performing incredibly well. The good coaches are the ones who acknowledge the physiological theory behind tapering but appreciate the individual athlete. Nothing should supplant that more intuitive understanding.

So, to taper or not to taper? The short answer: It depends. Experiment to figure out what works best for you. No matter your approach, dedicate yourself to it. That’s the only way to get the most out of your taper period, and all the training that came before it.

1 Comment

Pingback: Ultramarathon and Trail Running Daily News | Ultrarunnerpodcast.com