Attention Uphill Athletes: Some of the nutrition information in this article is now outdated. While certain highly trained endurance athletes like Cory and Adrian may benefit from fasted training and other nutrition strategies, our coaches and dietitians no longer recommend these strategies for most athletes, especially female athletes. You can read more in our most recent nutrition and fat adaptation articles, written by Uphill Athlete’s registered dietician Rebecca Dent and reviewed by the Uphill Athlete team, that reflect the most up-to-date scientific findings on fat adaptation and fasted training.

If you need further advice, we encourage you to reach out for 1:1 coaching or 1:1 nutrition coaching.

Everest season is upon us. Two athletes that Steve House and I have coached—Cory Richards and Adrian Ballinger—are currently in Tibet at Everest Base Camp to attempt the world’s tallest peak without supplemental oxygen. We wanted to give a behind-the-scenes look at our approach to training these two. Below is my story about working with Adrian. In case you missed it, check out Steve’s story about working with Cory.

The first thing to understand about Adrian Ballinger is that he has a high capacity for work. His long list of accomplishments includes being the only American to have skied two different 8,000-meter peaks, including the first ski descent of Manaslu, and being the first person to summit three 8,000-meter peaks in a three-week period. In other words, he’s a pretty fit guy who’s certainly no stranger to big mountains.

It was a bit of a surprise to him when, last year, he had to turn around just shy of the summit on a no-supplemental-oxygen climb of Everest. He got too cold to continue. Not to say that making a climb of Everest sans oxygen tank is ever easy, far from it. But for a climber of Adrian’s prestige, fitness, experience, and skill set, there had to be something wrong—and I was pretty sure I knew what.

Adrian’s partner at the time, Cory Richards, was being coached by Steve, and sending us daily updates about his progress, so I was able to monitor Adrian throughout his climb. When Adrian had to turn around but Cory was able to continue, I really started to connect some of the dots.

A few months later, Adrian contacted me to get some help for another Everest attempt in 2017. By then I had a hypothesis that explained what had gone wrong, which I shared with him. To be positive, though, I wanted to verify what I suspected was causing his debilitating cold stress on a metabolic level by means of a lab test. He agreed, and sure enough, when the lab test results came back, my hypothesis was validated.

At the time of Adrian’s climb in 2016, he was heavily reliant on eating some kind of high-energy bar, gel, or similar product at once-an-hour intervals. What that immediately told me was that his metabolic preference was heavily shifted toward carbohydrate use. We often see this phenomenon with many long-distance athletes because they’ve been led to believe that if they aren’t fueling hourly during their workouts, something’s wrong. A huge industry exists to sell energy bars and gels, and there definitely is a time and a place for these sorts of fuels. What we see all too often is that an overreliance on such products can inadvertently shift the metabolic preference to carbohydrates. That’s precisely what Adrian had done, which the lab test confirmed.

At the time of Adrian’s climb in 2016, he was heavily reliant on eating some kind of high-energy bar, gel, or similar product at once-an-hour intervals. What that immediately told me was that his metabolic preference was heavily shifted toward carbohydrate use.

When Adrian’s test results came in, I walked him through the physiological processes that led to him getting so cold. Being highly reliant on carbs caused two exacerbating effects:

- Glycolytic metabolism, as compared to fat metabolism, is relatively stressful on the body. It produces a number of metabolic by-products that are hard for the body to deal with. Repeated high-energy activity that relies primarily on glycolytic metabolism, especially in combination with the reduced oxygen level present at higher altitude, tends to cause a stress to the body.

- Since we have very limited glycogen storage capacity and since consuming enough carbohydrate calories in the cold with a suppressed appetite is difficult, Adrian was very likely in a glycogen-depleted state.

The outcome of this combination created a stress reaction we have seen many times. In Adrian’s case, his body’s response was the shunting of blood from the extremities to the core in order to preserve the vital organs. This is very likely why Adrian’s hands and feet were becoming so cold, eventually forcing him to turn around before Everest’s summit.

I told Adrian he needed to do a 180-degree turn in his training and his dietary habits—which can be a hard thing for a widely recognized and respected athlete at the top of his field to hear. But because he had black-and-white test evidence he could see, and because I explained the physiology behind what happened on Everest, he bought in with 100 percent confidence and commitment.

His commitment made him great to work with. We were able to take his high working capacity and shift it into the type of training that we know is so effective. Soon he was training at a high volume, 20-plus hours per week, but in the right intensity zones. We also made some dietary shifts, which were suggested by the metabolic testing mentioned earlier, doing many of his aerobic workouts in a fasted state.

Initially, it was very hard for him to do his low-intensity workouts without eating before and during workouts because he was so accustomed to his previous eating patterns. But almost every week we were seeing gains in efficiency. Soon he was doing 4-to-5-hour workouts without eating anything, and feeling more and more energetic the whole duration of the workout. This was a good indication that his body was learning to utilize fat better.

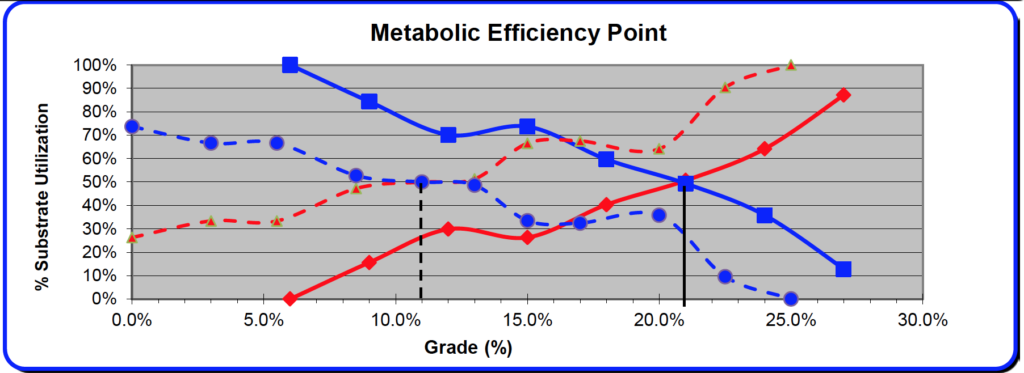

Adrian had heard the theory, seen the test results, and then experienced continual gains throughout our training. About a week ago he went back to the lab at UC Davis, conducted the exact same tests, and saw enormous improvements, as shown in the following graph.

Here you see Adrian’s two lab tests. The dashed lines are from December 2016, the solid lines from April 2017. Blue = Fat. Red = Carbs. The lines show the percent of total calories from fats and carbs at increasing intensity, with speed held constant and grade increased. The crossover point (50 percent fat:50 percent carb) is called the Aerobic Threshold (AeT), and is a measure of the basic work capacity of the aerobic system. His AeT moved from 11 percent to 21 percent grade, a near doubling in steepness for the same metabolic stress. This will directly translate to improved performance in the mountains.

Adrian is headed back to Everest as a different athlete this year. He’s fat-adapted and possesses greater knowledge of his body’s metabolism and stress responses. Ultimately, the success of a climb of Everest without supplemental oxygen has so much to do with external factors that nothing is a guarantee. But Steve and I, as well as Adrian, feel very confident about his chances this go-round, and all of us here at Uphill Athlete are rooting for him.

This article was originally published by Scott Johnston.

Update: Adrian successfully submitted Everest without supplemental oxygen. Listen to him and Scott Johnston discuss the trip on this podcast episode.