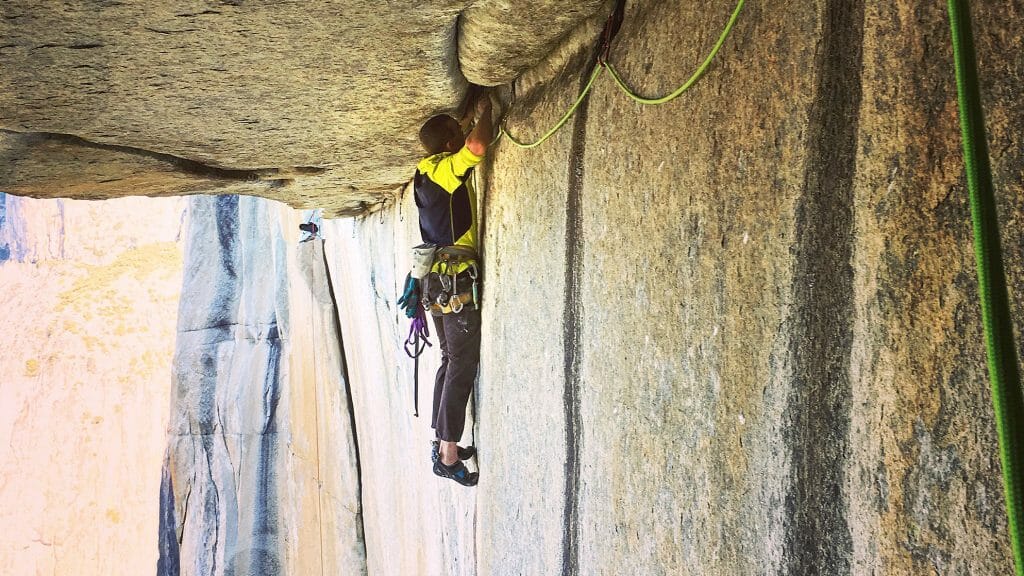

It was the end of our fourth day on the wall, and the final 5.13a pitch was giving me fits. Not because the climbing was all that hard, but because I was so tired. Fresh, well fed, and hydrated, I could have flashed the short traverse. But it was a different story now that I was exhausted and under the gun.

-by Josh Wharton

Matt Spohn and I had started up Muir Blast to El Corazon on May 15 with the goal of free climbing El Cap ground up—a goal I’d been working toward over the last few years. Everything had finally come together: weather, a partner, conditions, and thinner crowds. We would tackle 31 pitches up the wall, including eight pitches of 5.12 and six of 5.13.

It’s uncommon for El Cap to be free climbed from the ground up. Getting around to the top via the East Ledges is relatively easy, so rapping in to rehearse pitches on toprope and stash gear and water is very much the norm. It’s a big wall with tricky—read hot!—conditions for free climbing, and hauling all your food and water from the base adds an extra element of blue-collar labor. Understandably, most people prefer to take a top-down approach.

But I thought it would make for a nice challenge, plus it would be a good building block toward my ultimate goal of flashing Freerider.

Training for this effort has been a slow and steady progression over a period of years—to the point where climbing 5.13 consistently over multiple days, while tired, is possible. I’ve always built continuous climbing, or ARC training, into my workout cycles, and when I write myself training plans, I generally prioritize indoor training over outdoor climbing. This means that when I do get to the crag, I’m generally fatigued and not performing at 100 percent. I do this intentionally: being able to climb well while tired is essential to big wall free climbing.

Long, difficult routes like the Hallucinogen Wall in the Black Canyon of the Gunnison, Dreefee in Red Rocks, and The Honeymoon Is Over on the Diamond helped me along the way. But the key to success on El Cap was improving my onsight ability and flash level. I needed to be able to execute pitches quickly while on the wall, and to that end I brought a “first try” approach to each session at the crag. It develops a level of fight, and beta-reading, that’s very useful on sustained routes like El Corazon.

Climbing a big wall ground up and all-free introduces a level of uncertainty that’s both exciting and stressful. It can be difficult to grasp how much of a difference this nuance in style makes until you’ve tried to free climb a route on El Cap. Early in our climb, for example, the Z-cord in our hauling ratchet broke. Matt and I had to haul using a 1:1 system, which added a ton of work and fatigue.

There were moments on days four and five where I was uncertain I could actually pull it off. The physical crux of the route was a 5.13b roof traverse on pitch 25 that involved pumpy underclinging on slopers with minimal feet. On a tight timeline it was hard to find an ideal sequence quickly, so getting through the pitch felt desperate. The mental crux—that final 5.13a—came just two pitches later.

I failed several times at the end of it on day four, and it was clear that I was just really tired. Even though his free attempt hadn’t panned out, Matt generously agreed to spend an extra night on the wall so that I could rest up and hopefully finish off the pitch the next morning. The gesture was perfectly in line with his positive, supportive attitude, and I hope to reciprocate it someday.

Still, I was stressed out. If I failed on this 40-foot traverse the next morning, all the hard work—plus Matt’s willingness to do overtime on our portaledge—would be for nothing.

After a restless night, I did the pitch first try in the morning without much trouble. Nerves calmed, stress stripped away, I clipped in to the anchor genuinely happy. Success is sweet, but success following hard work is sweeter still.

The route was an amazing learning experience in many respects. I’d already integrated numerous technical tricks into my big wall quiver, like having the follower use a Petzl Micro Traxion instead of getting belayed, but it’s clear I still need to improve my hauling system if I want to save energy on future routes of this caliber.

The climb also underlined the value of long-term training. Committing to training on the order of months can be great for achieving short-term goals, but approaching your training with a multiyear outlook will help you achieve dream climbs that might seem impossible at your current level. Several years ago, before I started training consistently, I never would have been able to climb 5.13 on my fifth day on El Cap, with all the fatigue I’d accrued from hauling. Now I can.

It’s also critical to drill skills specific to your goal. If you’re someone with limited time, and you want to improve your climbing technique in a quantifiable way, focus on what you need to work on to succeed. In my case, it was increasing my onsight level.

Big wall free climbing may be a somewhat contrived game, but it’s also hugely rewarding—completely worth the training and effort. And that unplanned extra night on the portaledge.

El Corazon via Muir Blast: VI 5.13b, with obligatory 5.12 R; 31 pitches

Dates of ascent: May 15–19, 2018