At the 2019 Audi Power of Four Ski Mountaineering Race, I learned that you can have a tough day and still come out on top. It’s all about arriving with consistent training, a solid strategy, and a specific goal. And it helps to have a teammate who complements your weaknesses. You can suffer through the race’s 26 miles and 10,000 feet of gain on just one of those elements, but the Power of Four is best approached with all four “powers” in your quiver.

This would be my fourth time competing in the race. My first go at the Power of Four, back in 2016, had me teaming up with mountaineer Vince Anderson. We finished in seven and a half hours. Over the next two years, with teammate Tim Faia, a compact athlete who’s a powerhouse on steep ascents, I cut a full hour off that first time. This year, as in past years, Tim and I hoped to match or improve upon our previous PR. Plus there was a new goal to chase: the race had been selected as the US Ski Mountaineering Association’s national championship for the team event. Tim and I wanted to crack top three in the masters division.

This was front of mind as I neared my peak in training. Uphill Athlete’s Scott Johnston has coached me through two skimo race seasons now, and I can feel the compounding effects of the consistent, focused training from year to year. I come from a cycling background, and the biggest shift I’ve seen in my skimo racing has come as a result of doing fewer bike miles and instead prioritizing hiking and running starting in midsummer. I’ve learned when to hang up the bike and instead work on building my base for winter. Scott has also introduced the concept of polarization into my training, where the bulk of my miles are easy—within Zone 1—and the hard efforts are short but done at a very high intensity—around threshold, Zone 4 and above. I’m no longer just dragging out a lot of time in Zone 2 or 3.

Three weeks before the Power of Four, I did a big-volume training camp (about 18 hours over four days), took a recovery day, then did a short local race. Everything went smoothly up to and through that peak. I was feeling really confident. Then right when I started to taper, at my most vulnerable stage, a common cold hit. For a good six days I couldn’t do much of anything. Eight days out from the race, when I was feeling better, I got in two solid workouts before going back into taper mode.

* * *

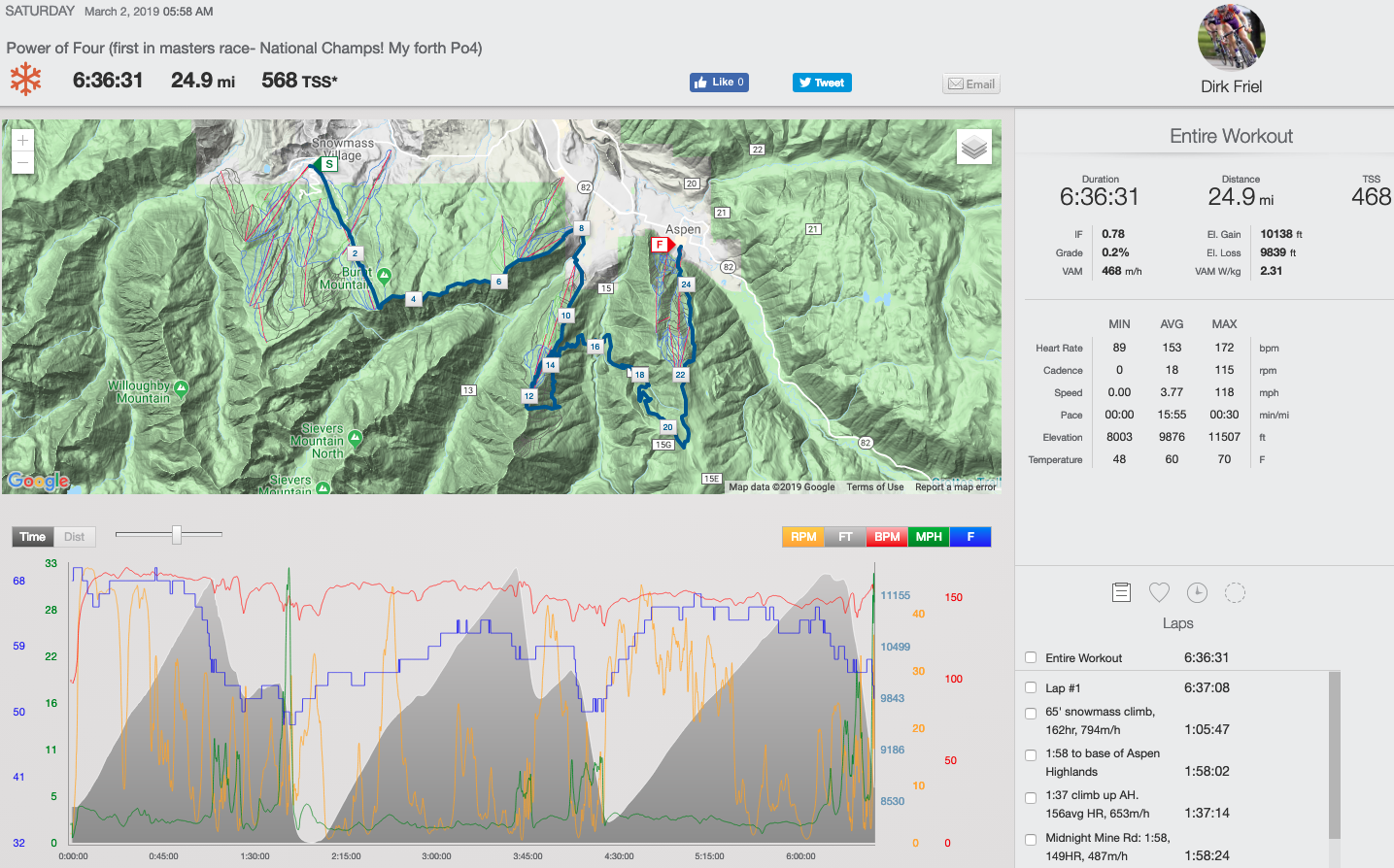

According to TrainingPeaks on the day of the race, my fitness—CTL (Chronic Training Load)—was 91. My TSB (Training Stress Balance), or how fresh I was, was +15. I knew I had a really good foundation, but sensed I probably wasn’t at the level I could have been. That weighed on my mind as we lined up for the start in Snowmass, surrounded by more teams than in previous years. The national championship designation had attracted some serious competition, but as with most skimo races, the vibe at the base was fun and friendly.

Tim and I had enjoyed a relatively relaxed morning. Unlike in past years, we’d opted to stay at a hotel in Snowmass, rather than in Aspen near the finish. The night before, as we’d sorted and debated gear in our room, we got the news that the course would change. It was snowing heavily, and avalanche danger had become a concern for the ridgetop boot-pack to the top of Aspen Highlands Bowl, as well as the drop into the bowl above tree line. While I was sad to miss out on the race’s most iconic segment, I knew the event would be easier overall without it. And not as cold. Staying below tree line all day, Tim and I wouldn’t have to deal with the winds or adding extra clothing.

But as we headed up our first climb of the day, it became clear that the Power of Four was still going to push me to my limit. Because of the aftereffects of my sickness, I was suffering. My heart rate was higher than I wanted it to be, and I just did not feel good. I was relieved we’d chosen to abandon our two-liter water bladders in favor of a few small, collapsible flasks we could refill at the aid stations. Shaving those three pounds off each of our race kits made the uphills slightly less tiring.

The course throws three big climbs at you: the first climb out of Snowmass, the middle one up Aspen Highlands, and a final big ascent before the last push down into Aspen. With the avalanche danger cutting the Aspen Highlands climb short, race organizers made up for some of the lost distance by lengthening the final ascent. The first climb took us about an hour, just 2 minutes slower than in the previous year. Aspen Highlands was about a 90-minute affair, and then the final climb took us 2 hours. Having never been on the new section that had been tacked on to this last big uphill, Tim and I didn’t know what we were in for. Every bend we turned, we kept thinking we were near the top. Then we’d see the next bend—and another and another. It felt really drawn out, like it would never end. Mentally, that was the hardest part of the race.

With Tim being stronger than me on steeper terrain, I was on tow for the middle and final climbs. Having a line between us helps me—not because Tim is always actually pulling, but knowing the line is there pushes me to sustain his pace. He has a higher cadence than I do, which is great. A lot of being fast is in your cadence, so it’s a constant reminder when he’s right in front of me to keep the cadence up. Tim and I didn’t talk a whole lot during the race. We’re usually pretty serious, saying only what needs to be said, checking in with each other periodically.

Our skin strategy this year ended up being a big time-saver. First, I brought along a wider pair for the Aspen Highlands climb, where the steeper grade normally has me slipping a lot. By using a pair of wide skins that had more grip to them, I was able to conserve energy. It didn’t matter that they didn’t glide as well. Then, thanks to a prerace tip from Max Taam, one half of the men’s winning team, Tim and I each saved a fresh pair of waxed skins for the final climb. This prevented “glopping”—snow freezing and caking onto the skins, making it impossible to glide. As that issue forced several teams around us to stop and clear or change their skins, we made it almost to the top of the climb without having to pause.

I was hurting on the final descent. You pass through a backcountry access gate, so you’re not on groomers. My legs were burning. By that point there was no doubt we would get to the finish line, that it would be over shortly, but that knowledge didn’t make the last downhill any easier. The conditions this year underscored that I need to become a better skier on race gear. Pushing through all the snow from the night before—about 10 inches of heavy, spring-type powder that only got heavier as the day warmed up—was an absolute eye-opener. Tim and I crashed, a lot. At least the landings were soft. It was a battle all the way to the end.

Our final time of 6:35:58.54 earned us first place in the masters division. The win sweetened what was otherwise a pretty painful day. The 2019 Power of Four could have gone better, but that’s what keeps us going as athletes: the pursuit of the perfect day. I do know that I felt more prepared than in previous years. My training was solid and specific, my teammate was as strong as ever, our new skin and water strategies paid off, and we chased down our goal. Even though I’m an older athlete, I’m still getting faster. There is still room for improvement—for getting closer to that perfect race.

-by Dirk Friel, TrainingPeaks co-founder