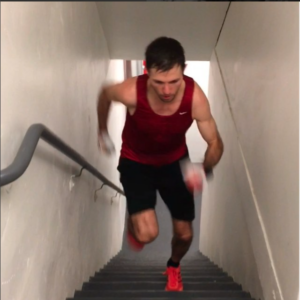

This is how David Roeske prepared to climb two 8,000-meter peaks without oxygen in a stairwell at sea level.

When I got back from Everest in 2013, I felt incredibly grateful and overwhelmed with my good fortune. The summit experience was powerful and transcendent for me, and I came back with a desire to share the inspiration I had found there. I also felt fortunate that my body had proven able to handle such a major leap in altitude from the levels I had previously climbed. In seizing the opportunity to go, I had accepted a substantial probability of having to turn around, and yet it had worked out. I couldn’t have asked for more.

Yet, there was a cloud of unfinished business lingering as I celebrated with the other summiters on the drive out of Tibet to Kathmandu. What I had really wanted to find out was if I could climb Everest by pure means, without supplemental oxygen. In the end, I took the more conservative and safer route, using O2 for the final 1,500 feet of elevation gain. I still had the most amazing summit experience in my life, but I had not succeeded in climbing the way I wanted.

I knew in the back of my head I wanted to go back. Being on a mountain like that—no matter what you accomplish—takes a lot out of you. I only had about 2 percent body fat going in, and I’m 6 feet tall and weigh about 150 pounds; so there were not a lot of reserves to run through. In just three weeks from Base Camp to summit I had lost 20 pounds. I came back famished, worn out, and eating everything in sight. While the weight bounced back in a few weeks, it took months to regain my prior fitness.

Even when I was feeling better again, making a return trip was not immediately on my agenda. One of the reasons I went for it in 2013 was that I thought the firm I was working for was likely to shut down, and that it was one of my last chances to take advantage of the goodwill I had built up over five years there. Indeed, that did happen. I found a new job in 2014, and I knew I couldn’t ask for more than a week or two off to do a big expedition any time in the immediate future. So returning to the Himalaya slipped into the background, temporarily.

I made a one-week attempt on Denali during this time, which went well through 16,000 feet, but my team got turned around by bad weather and we were not able to summit. Outside of that, for the next couple years I made my regular outdoor trips to Colorado, but no other major expeditions.

But all the while, the steady draw to return to the high mountains was building beneath the surface. As the saying goes, “the best alpinists are the ones with the worst memory.” The depletion and suffering fades, and you just remember the views, and the ineffable joy of being on top of the world.

In the fall and early winter of 2015 and 2016, that percolating desire had grown into a concrete plan to return. I had unfinished business with Everest, and myself. One of my favorite Instagram posts from Steve House is one he posted of a solo mission in the Karakoram. Part of his caption reads, “I really needed to know. Glad I do.” In the same vein, I needed to go back and find out if I could meet the challenge of Everest by fair means.

But I also knew that I didn’t want to just go back and see the same route on the same mountain all over again. Part of the draw was the personal test, but I also wanted to just be in those mountains, to climb new peaks and see new vistas. So I came up with the crazy idea to try linking multiple 8,000-meter peaks.

On the Tibetan side, Cho Oyu and Shishapangma are both within a day’s drive from Everest Base Camp. So I started talking to my climbing outfitter at SummitClimb, Dan Mazur, about whether he could arrange permits for multiple peaks for me. He found he could, so at the beginning of February, I nervously asked my boss for the time off.

In finance, taking anything more than a week off is excessive, so asking for six weeks seemed as though it could risk my employment. But I had to ask, and was blown away when my boss gave me the okay, and said the firm wanted to support me in the expedition. I am profoundly grateful and lucky for such support, and I gladly brought some company flags along to photograph from the top.

When I got the green light, I began thinking about how I would have to train differently this time. I was already in excellent running shape, but I knew that a goal as ambitious as mine would require better training than anything I had done in the past.

I had gone to Steve House’s unveiling party for his and Scott Johnston’s book, Training for the New Alpinism, at the Patagonia Meatpacking store in New York City in 2014, and his presentation stuck with me. As I thought about my goals in 2016, it was clear to me that Steve would be the best possible person to help me with my training needs.

So I emailed him in February 2016 and asked if he could guide me in Colorado for a day, to glean what I could from that experience and discuss my future plans. Steve was booked up and busy with a new baby, so he set up the initial call between me and Scott.

Scott and I discussed in great detail my prior training, fitness level, and what had and hadn’t worked on Everest in 2013. The conversation was enlightening. Scott is an incredibly data-driven guy who has gone through all the research on physiology and the specific training modalities needed for high-altitude mountaineering.

Before we spoke, I had been planning on purchasing their basic training plan. But after speaking with Scott I realized how valuable his constant feedback and calibration of the training plan would be, and I decided that the Master Coach service was absolutely worth it. I believe the training one does for an expedition like this is the biggest factor, aside from weather, in determining whether you succeed—and for the amount of money an expedition costs, the extra cost of premium coaching is de minimis compared with the effect on success it can have.

I was super excited to have full access to Scott and to be working with him for the next few months. And I was psyched for the hard work I knew he would throw at me. We started with a battery of diagnostic tests to ascertain my metabolic levels, and work out a proper training plan.

Again, like my previous trip to Everest, I only had a few months available to train specifically for the mountain. Thankfully I was already at a very high level of fitness, but I would highly recommend other people start working far sooner than two and a half months before a Himalayan expedition. But that was the time we had, and we did the best we could with it.

In the beginning, it involved tons of time on the treadmill. I would set it on the steepest incline the machine would go, and spend up to 3 hours at a time hiking at a fast clip with a pack on, wearing mountaineering boots. This was more difficult mentally than physically. It was boring. I was working full-time, and had a girlfriend as well—so taking 3 hours out of my night to walk on a treadmill was not exactly an exciting way to spend my free time.

But it steadily got harder. As the training progressed, the exercises moved from the treadmill to the stairwell. The building I live in has 40 floors, and my assignment was to hike laps of the building with a weighted pack, riding the elevator down, at a specific exertion level for hours at a time. I would tackle the longest assignments on the weekends, since that was when I had more free time, and even then I would usually put it off until Sunday.

I remember countless times getting up slowly on Sunday morning, having coffee with my girlfriend, trying to put off the inevitable as long as possible, and then finally, sucking it up and heading for the lonely stairwell. If you’ve never done this before, it’s difficult to describe how psychologically challenging this workout is. Time moves much slower than it does in the mountains. Meanwhile, it’s no cakewalk, physically, either. I would consistently crank out 7,000–8,000 feet of vertical gain with a heavy pack. The only thing that kept me sane was listening to audiobooks.

In fact, I remember listening to The Martian, which is a story (as you probably know) about a guy being incredibly resourceful because he’s stuck on Mars. His determination was something I could relate to. Hiking upstairs over and over all alone in the big city was surreal, and felt a bit like being on a deserted planet myself.

It was amazing to watch my development during the training. At first, Scott had me doing my workouts with just 5–10 pounds in the pack. By the end, I was carrying 30 pounds for over 4 hours at a time on the weekend and 2 hours at a time during the week. Scott was trying to build my basic fat-burning aerobic capacity, which allows you to perform during long days in the mountains. I would track my lap times up the building, and found that as the hours would go by my laps were naturally going faster and faster. Scott explained that this was evidence that my body was turning on the fat-burning engines, and getting more efficient at it during those sessions.

By the time we finished I had put in some really big days. My body felt strong, and my legs had definitely put on muscle mass. I totally changed my fitness abilities from being able to go very fast for short- and medium-distance road races, to very hard for hours and hours on end up hills. This perfectly simulated the type of work you do on a major mountaineering objective like an 8,000-meter peak, and I felt the difference when I got to Tibet.

I knew when I left on April 20 that I was not only in the best shape of my life, but also in much better shape for mountaineering in particular than I had been in 2013. But with something like Everest without oxygen, when the odds are so against you, there are still plenty of doubts. Physical fitness aside, there are always serious risks associated with simply climbing the standard route on Everest. Nothing is a given, and nothing should be taken for granted. To say I felt butterflies about my objectives would be an understatement. But I knew I had put myself in the best position I could, thanks to incredibly precise coaching and my own hard work. Now it was up to me to execute as well as I could, and leave the rest up to the mountains.

-by David Roeske

You May Also Be Interested In:

- A Himalayan Odyssey, the story of David’s success on Cho Oyu and Everest

- Seize the Day: David Roeske’s Road to Everest in 2013