We know from decades of training and coaching that the best way to measure and regulate intensity, in order to stay under your Aerobic Threshold, is through a combination of monitoring your breathing and your heart rate. How do we apply that to training?

What Is Intensity?

Intensity is how hard you’re working and is a reflection of what metabolic pathways are fueling your movement. A dog walk is low intensity. An all-out sprint is high intensity. Almost all successful mountaineering is carried out at low to moderate intensity.

The Two Breathing Thresholds: Real-Life Examples

Steve has worked as a professional mountain guide since 1991. One way he knows he’s at a pace most clients can handle is that he can breathe with his mouth closed or carry on a conversation without losing his breath. This point is called the First Ventilatory Threshold 1 (VT1) or the Aerobic Threshold (AeT). You can read Part 3 of this series to learn more about what it means in terms of physiology.

As your climbing speed increases, however, at some point you’ll start to breathe heavily. The point at which you can no longer speak a full sentence in one breath is referred to as the Second Ventilatory Threshold (VT2) or the Anaerobic Threshold (AnT). If you’ve ever climbed with a good guide, they’ll often engage their clients in conversation while climbing. While conversation is important on many levels, in this case it also serves as an excellent way of accessing the climber’s exertion level. If that climber is gasping for breath, they’re on borrowed time and will need to stop within an hour. We’ve all been there and it is important to recognize the implications of the intensity to your day’s climb.

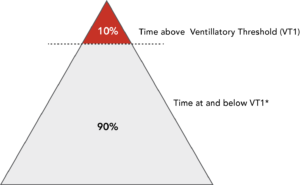

In reality our aerobic and anaerobic metabolic systems are always working in concert to produce the energy you need for climbing. The aerobic system is best trained by spending the vast majority of your training hours (80–90 percent) at and below VT1/AeT. The anaerobic system gets sufficient training for mountaineering by spending approximately 5 percent of your overall training volume between AeT and AnT, and another 5 percent above AnT. How fast you climb is determined, first and foremost, by the efficiency of the aerobic system.

The Aerobic and Anaerobic Systems

The aerobic system burns fat at low intensities. This process is, physiologically speaking, very efficient. As long as you stay at low intensity (<VT1/AeT), the length of time you can climb is limited only by fuel stores, which you can replace by eating.

The anaerobic system produces metabolic by-products, the accumulation of which actually slows the anaerobic energy pathway in a negative feedback loop. The aerobic system acts like a vacuum cleaner, sucking up and utilizing these anaerobic by-products. The stronger that vacuum cleaner (the larger the aerobic capacity), the more anaerobic work that can be done.

Therefore, the better trained the aerobic system is, the faster and longer you can move.

Conclusion

Let’s summarize:

- The intensity of your breathing is a direct, real-time measure of the intensity of exercise.

- Breathing depth and rate offer a personalized, instantaneous metric for each athlete to control training intensity.

- Heart rate monitoring should be done continuously and in conjunction with breath self-monitoring.

- A pace at or below your AeT should make up 90 percent of your endurance training volume. This is true for those starting a training program and for highly accomplished pro-level climbers. In Training for the New Alpinism, as well as in many other sports, we call this Base Training.

This is Part 2 in a series of three articles. Read Part 1 and Part 3 here: