Often when I mention strength training to female athletes, it conjures up images in their minds of big bulky men throwing around barbells stacked with weight plates. When it comes down to it, strength training is working to keep our bodies strong, protecting our ligaments, and building up the strength to help us maneuver our mountain goals. That doesn’t mean looking like a bodybuilder or doing CrossFit pull-ups on repeat. It means doing the little movements and techniques that help us balance, step and push off better and more effectively as we climb, run, and move.

In athletics, females have been guided to strength train in the same fashion as men. And although this isn’t necessarily detrimental, it isn’t considering our unique physiology. Females are different, physiologically speaking. That is just the truth, and we can train like our male counterparts or use our differences to make us even stronger and more resilient using the knowledge of our differences. That is what this article is aimed to do. Give you the knowledge of differences in the female body regarding strength and empower you to know why that is important and how we can train with that information.

KEY PHYSIOLOGICAL DIFFERENCES BETWEEN MALES AND FEMALES

It is important to remember that when we look at the differences between female physiology and male physiology, we aren’t comparing to say one is better or stronger than the other. We are showing HOW we are different so that when we come into a blanketed strength training program, we know that there are differences between the male and female body that will determine how we train.

When it comes to muscular differences, males have approximately 50% more strength in their upper bodies and 30% more strength in their lower bodies compared to females (6).

From a muscle fiber perspective, males have more type 2 fibers, which is the fast twitch fiber. Because of this, males have, generally speaking, more anaerobic power. This means short, quick, and powerful movements. Overall, their bodies are larger in mass compared to females and they carry less body fat.

Females tend to have the smaller lung capacity and lower VO2 max because of smaller body frames than males. The lower VO2max is partly because females have thinner left ventricle walls, leading to less cardiac output. Cardiac output is how much blood the heart pumps out in a given time. While we are on the topic of blood, female bodies carry 10-16% less hemoglobin than males. Hemoglobin is the protein that carries oxygen in our blood. However, because of our smaller frames, the composition of more type 1 fibers (slow twitch), and our ability to metabolize fuel, females are more resilient in endurance and more resistant to fatigue.

Hormones play a key role in male and female physiological differences as well, including the hormonal fluctuations that females experience from month to month and life stage to life stage, which we will go over in more detail later in the article.

One major difference between males and females hormonally as it relates to strength is males have around 15 times more testosterone than females.

Testosterone is the hormone that contributes to strength, hypertrophy, and power. With all that being said, females fatigue slower than men and at equal rates across our bodies. Whereas males fatigue quicker in their lumbar musculature. And when it comes to recovery, females recover faster than males.

What does all this mean in the overall scope of things? We, as females, are built differently. Our musculature and hormones are different, and how we train and recover should be different with that in mind. It doesn’t mean that females are inferior to males or vice versa. Simply put, we are different; our strength training will also differ from our male counterparts.

WHY IS STRENGTH TRAINING IMPORTANT

The question sometimes arises of WHY females need to strength train. Especially with my ultrarunning and mountaineering athletes, the volume of time it takes to run or climb leaves little time left for anything else, let alone strength training. But strength training is invaluable for so many reasons.

For one, from a health perspective. Strength training helps prevent diseases (9) and limits our chances of diabetes, obesity, heart disease, etc. It helps with hormonal control, mood enhancement, brain function, and energy levels. Strength training helps with bone density, preventing us from getting stress fractures and decreasing our chances of osteoporosis.

From a sports perspective, strength training prevents us from getting injured and improves sports performance. Our biomechanics for running and climbing is good, but remember that our joints, such as our knees and shoulders, are held together and moved based on strong muscles, ligaments, and tendons. By strengthening all these things, our biomechanics function better and respond better when something unexpected happens, such as a foot slip or a fall. Strong legs help us power up mountains, strong arms allow us to swing the ice axe, and a strong core helps in all these things.

But the main reason from a sports performance perspective is the reduction in sports injuries. Strength training promotes strong ligaments, joints, and bones, all of which help us stay healthy and active.

From an injury prevention perspective, some of the main reasons strength training is beneficial are increased proprioception, stability, and balance.

Strength training increases our ability to understand how our body is and moves about the world around us, otherwise known as proprioception. Our body can understand how and when to move, especially on technical mountain terrain, which is incredibly important. For balance and stability, it is no surprise that this is of utmost importance when performing in sports where this is a crucial aspect, such as all mountain sports. Whether climbing, running, skiing, or touring, balance, and stability are essential to ensure you do not fall and maintain a smooth cadence in your movement.

Strength training also trains our brains to perform movement patterns correctly. Repeated and loaded movement leads to muscle activation patterns that our body remembers when we are in our sport. All that work in the weight room translates to your brain sending chemical messages to your muscles on the correct and appropriate way to load as you perform on the mountain. Essentially, you are teaching your muscles how to fire together as a cohesive team and in the correct way.

And, of course, protecting our bones and ligaments is the number one reason for injury prevention with strength training. Among all these reasons, building a solid base to work off of to prevent muscle tears, ligament sprains, and bone fractures is essential. We always need a solid base to perform our best; a strong one also means a protected body. Especially as female athletes, how our body is built puts us at higher risk for certain injuries. Let’s dive into that to understand better how important strength training is for females.

SPECIAL INJURY CONSIDERATION FOR FEMALE ATHLETES

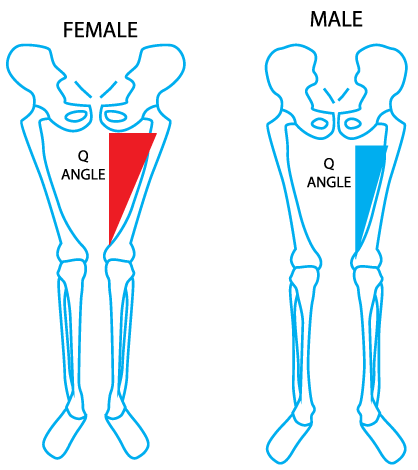

As we have discussed, female bodies are built differently; part of that is the structure of our lower body. Females have a wider Q-angle. And if that sounds like some odd geometry lesson you missed in high school, don’t worry; it isn’t that complicated. The Q-angle is the quadricep angle between the anterior iliac superior spine (near the outside of the hip bone) and the tibial tubercle (right below the knee joint). This inverted triangle is known as the Q-angle; females have a 17-degree angle on average, while males, on average, have 12 degrees.

This increased angle leads to lateral knee movement, less hip and knee flexion, increased hip internal rotation, and muscle imbalances. Muscle imbalances, in this case, can be seen in stronger quadriceps versus the muscles in the posterior chain (backside of the body), leading to muscle strains and tears. Due to the tracking of the knee and the difference in hip and knee mechanics, this can also put more stress and improper movement patterns in the knee joint.

Females are 3-5 times more likely to have ACL tears (4) due to the q-angle and other physiological differences than men.

When we think of ACL tears, we think of football players or soccer players slamming into each other, but in reality, 70% of ACL tears occur from non-contact injuries.

Knowing about the q-angle and the differences it provides for females is essential because we can use this knowledge to train appropriately with this in mind. That means focusing on posterior chain exercises, hip strengthening, and stability.

Key Exercises:

- Glute bridges

- Banded hip walks

- Single-leg deadlifts

Another injury considerations are bone injuries. As mentioned above, strength training helps promote strong bones, but females especially need to be aware of their bone fracture risks. The prevalence of bone fractures in females is higher than in males, which is due to the size of our frames and bones and our lower bone mineral density (1). The prevalence of osteoporosis in females is more than four times that of men, and the likelihood of bone fractures is twice as high (9).

RED-S (Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport) exacerbates this likelihood of fractures, which, although it affects both genders, is way more prevalent in females.

RED-S is when energy expenditure is higher than what the athlete is taking in, leading to several health issues, including bone fractures.

The good news is females tend to recover better from bone fractures, but that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t train to avoid them to the best of our ability. To do so, strength, strength, strength. Resistance training increases bone density by pushing and pulling on the bones to stimulate the bone cells to grow.

Check our our article on Nutrition for the Female Uphill Athlete of Menstruating Age.

Key Takeaways:

Incorporate strength training to improve your performance on the mountain and prevent disease and injuries. This can be done with gym weights or even bodyweight exercises like pushups and squats. Don’t know where to start? Check out our Chamonix Fit Program!

Chamonix Mountain Fit

FEMALE LIFE CYCLES AND STRENGTH TRAINING

When considering starting or continuing a strength training program, it is important to be armed with the most knowledge you can about your body. Female athletes are incredibly unique in that throughout our lives, our physiology and hormones change pretty dramatically depending on our life cycle. We can go through hormonal fluctuations each month, from growing human life to ending the menstruation phase of our life. All of these have dramatic changes in how we train and how we react to strength training.

MENSTRUAL CYCLE CONSIDERATIONS

When female athletes start menstruating, there are dramatic shifts in estrogen and progesterone in our bodies each month. To go into more depth on this information, check out our female physiology article. It is important to know that each female responds differently to their menstrual cycle, like everything in life, but there are some key things to keep in mind throughout the menstrual cycle that can help you plan and prepare for training. Let’s get into a very simple way to consider strength training as it relates to your cycle.

The first phase of your menstrual cycle is called the follicular phase. This is when your period begins and lasts until ovulation. During this time, your estrogen begins at its lowest and slowly increases. Progesterone at this time is low. This is the ideal time for strength training as estrogen helps promote strength gains.

After ovulation is the luteal phase, this phase estrogen drops dramatically and slowly increases, and progesterone increases. Your body needs extra fuel during this time, and you might feel more fatigued. This phase is to go easier, fuel, and hydrate well.

Key Takeaways:

During the first half of your menstrual cycle, hit the weights! Take advantage of the hormone fluctuation and its benefit on muscle gains. In the last half of your cycle, listen to your body and fuel up!

CONSIDERATIONS DURING PREGNANCY

During pregnancy, we have a lot going on with our bodies. From hormones to our bodies shifting to carrying weight in different ways, this is a critical time to listen to your body and your doctor. If you have a healthy pregnancy and have been cleared for exercise, there are several things to keep in mind. For one, the shift in hormones and the introduction of a very important hormone that will affect your training, and that is Relaxin. Relaxin helps your body expand and make room for the baby by creating laxity in your ligaments. This is great for letting your body expand, but keep in mind that laxity in ligaments can also lead to sprains and strains, so be careful and aware.

Along the same lines, your body is growing in different directions, which means your balance and stability will be off during this time. Now is a great time to work on stability exercises with support. Also, be careful not to do exercises that may put you out of balance. There is a better time to try to stand on a physioball while doing shoulder presses!

Next up are our glutes and core. When pregnant, our mechanics work differently. That means that we are engaging muscles differently. One of the muscles that get more neglected during this time due to the change in movement mechanics is our glutes. Our glutes tend to take a back seat when walking, running, etc, during pregnancy. Our abdomen is also expanding at this time. This often leads to the linea alba, which is the tissue between the two abdomen walls expanding or tearing and creating a gap between the abdominal walls to make room for the expanding belly. This separation in the walls is called Diastasis Recti, and although it sounds painful, you most likely will not even know you have it. Though, as we touch on in the postpartum section, this is a very important thing to learn about after giving birth. Finally, knowing where you are in your pregnancy journey is important, as that will dictate what you can and cannot do safely. After 20 weeks, you do not want to do any exercises that have laying supine (face up) as the weight of the growing belly can press on the large blood vessels in your body and significantly decrease your blood pressure. This is dangerous because it can cause dizziness, lightheadedness, and fainting. For the fetus, it can lead to restricted blood flow, thus inducing reduced oxygen and a decrease in heart rate. So, when doing exercises that would normally have you lying down (chest press, etc.) ensure you are in an elevated position. And, for any pregnancy, consult a physician to ensure you and your baby are healthy and can progress with exercise safely.

Our Favorite Strength Exercises During Pregnancy:

- Goblet squats

- Bird dogs

- Glute bridges

- Side planks

POSTPARTUM CONSIDERATIONS

Ok, you just had a baby. Congrats! Don’t go jumping into exercise the next day! Your body just went through an amazing process and needs healing. Your doctor will usually clear you in 4-8 weeks based on your birth. Once cleared, it is important not to jump into pre-pregnancy levels immediately. We have many things to consider now, and we can set ourselves back pretty quickly by going too fast too soon. A lot of things happen when we have a baby, but we are going to go over just a few of the main ones to consider when it comes to strength training.

For one, build slowly and carefully. Your body has changed, and things will move and react differently. Depending on whether you are breastfeeding or not, relaxin is still in your body during breastfeeding, meaning your ligaments are still loose, and juking and changing positions quickly are not ideal in this phase. Also, if you are a trail runner, be aware of your steps and mindful that ankle sprains are more likely during this time.

Your core is different now. 60% of women experience Diastasis Recti (DR) postpartum (3). The last section shows a tearing in the linea alba that creates a separation in the abdominal walls. From my experience in coaching postpartum women for over a decade, most women do not know that they have diastasis recti, and their doctors tell most that they do not have it when they do. Here is an easy way to check yourself for abdominal separation (insert video). With this in mind, if you have DR (and even if you don’t), it is important to strengthen your core correctly and safely. That means avoiding exercises that have your head and feet off the ground simultaneously (boat pose), sit-ups, and twisting motions (Russian twists). DR left uncared for will lead to incontinence, low back pain, abdominal hernias, and more.

Your glutes and pelvic floor will likely also need some attention. Ever tried jumping or sneezing after having kids? The fear. Well, you don’t need to live in fear; work on strengthening your pelvic floor to help prevent those moments of panic.

Our Favorite Postpartum Exercises:

- Glute bridge with abduction and adduction

- Side plank hip dips

- Bear hold

- Squats

PERIMENOPAUSE AND MENOPAUSE CONSIDERATIONS

During perimenopause and menopause, again, our bodies undergo many changes. Our estrogen is dropping, and our muscle mass and bone density are decreasing. On top of this, joints are stiffer. Staying on top of strength training during this time is more important than ever. Balance is another important factor at this time. Due to the lower bone density and challenges in balancing, now is not the time to take on intense high-impact sports such as building jumping and skydiving.

During menopause, females lose approximately half a pound of muscle annually (5). This, coupled with a decreased metabolic rate, causes female body composition likely to change with inactivity. Strength training can help combat this loss of muscle mass so we can maintain or even gain muscle during this time in our lives. If that weren’t enough good news, with the lowering of bone density during menopause, we know that strength training can help maintain bone mineral density. And the dreaded hot flashes? Strength training helps minimize that as well. All in all, females in perimenopause and menopause should be staying on top of strength training.

Our Favorite Menopause Strength Exercises:

- Shoulder presses

- Back flies

- Plank

- Reverse lunges

SUMMARY

Female athletes are incredibly strong and adaptable human beings. Our bodies take on a lot and adapt to intense changes in our hormones and our body structure. All while doing this, we keep being amazing and inspiring athletes. The main thing to remember is that knowledge is power. Yes, our physiology is different from males but we are not inferior by any stretch. Knowing our differences can help us train appropriately for OUR bodies in a world that has been dominated by a male-centric definition of fitness and training. We are not small men, and it is important to treat our training in a way that represents that. Find strength in our incredible female physiology and use that to your advantage in training and life.

References

- Cawthon, P. M. (2011). Gender differences in osteoporosis and fractures. Clinical Orthopedics and Related Research, 469(7), 1900-1905.

- Haizlip, K. M., Harrison, B. C., & Leinwand, L. A. (2015). Sex-based differences in skeletal muscle kinetics and fiber-type composition. Physiology 30(1), 30-39.

- Keeler, J., Albrecht, M., Eberhardt, L., Horn, L., Donnelly, C., & Lowe, D. (2012). Diastasis Recti Abdominis: A survey of women’s health specialists for current physical therapy clinical practice for postpartum women. Journal of Women’s Health Physical Therapy, 36(3), p 131-142.

- Mattu, A., Ghali, B., Linton, V., Zheng, A., & Pike, I. (2022). Prevention of non-contact anterior cruciate ligament injuries among young female athletes: An umbrella review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(4648).

- Mishra, N., Mishra, V. N., & Devanshi. (2011). Exercise beyond menopause: Dos and Don’ts. Journal of Mid-Life Health, 2(2), 51–56.

- Nindl, B. C., Jones, B. H., Van Arsdale, S. J., Kelly, K., & Kraemer, W. J. (2016). Operational physical performance and fitness in military women: Physiological, musculoskeletal injury, and optimized physical training considerations for successfully integrating women into combat-centric military occupations. Military Medicine, 181(1), 50-62.

- Nuzzo, J. (2023). Narrative review of sex differences in muscle strength, endurance, activation, size, fiber type, and strength training participation rates, preferences, motivations, injuries, and neuromuscular adaptations. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 37 (2), 494-536.

- Varnes, J. R., Stellefson, M. L., Janelle, C. M., Dorman, S. M., Dodd, V., & Miller, M. D. (2013). A systematic review of studies comparing body image concerns among female college athletes and non-athletes, 1997-2012. Body Image, 10(4). 421-432.

- Westcott, W. L. (2012). Resistance training is medicine: effects of strength training on health. Current Sports Medicine Reports, 11(4), 209–216.

Strength Training for the Female Uphill Athlete

Table of Contents