The first video in the Alpine Principles video series is titled “Perfect Preparation.” That this title is first about making judgments in alpine climbing, mountaineering, ski mountaineering, and mountain running is neither an accident nor a coincidence. In fact, a major subprinciple of this concept, which Uphill Athlete is dedicated to, is physical preparation. Since we have that pretty well covered I will dive into ideas of motivation, partners, patience, covering your bases, and knowing what you don’t know.

Understand Your Motivations

Understand why you’re there, why you want to go there. This is the first step and one of the most nebulous, and therefore most difficult. Difficult because it’s often hard to have clarity on any given day, and more complicated because it can change on a near-daily basis. I mention this to set the stage for the complexity—and importance—of this step.

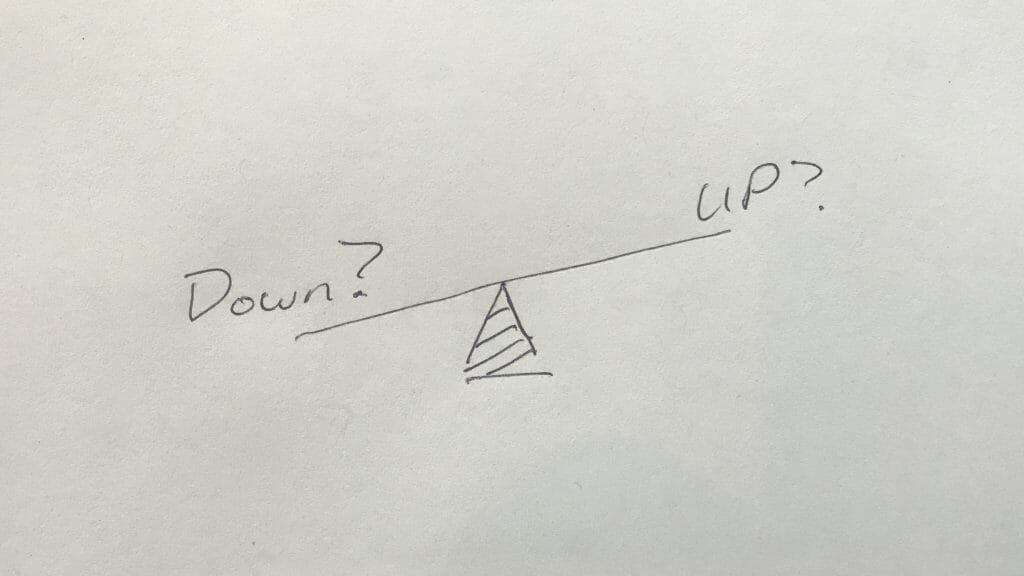

Motivations are important because our emotional state has so much to do with our ability to understand and evaluate risk. When I feel angry or frustrated, I am likely to take on more risk, largely by spending less time evaluating it. Pissed off, I barrel ahead. When I’m more at peace, I’m more willing to contemplate and have a rational “out-loud” discussion about the risk of a given situation. Out-loud meaning I can tell my partner, and frequently do, what I think about the current risk/reward balance and why I think we should go up, or go down. Remember that this decision seems black and white: up vs. down. But it’s rarely like that. It’s a teeter-totter.

The Three-Way Teeter-Totter

In most situations, the reasons for continuing up may weigh more than the reasons for going down. But at some point something may happen to upset that balance: the wind might shift, loading snow onto our descent route, which we already worry might be prone to avalanche. The temperature might start to warm more than expected, sending rocks falling down past us. However, the fact is that most of the time the reasons for up outweigh the reasons for down.

The second most common scenario is when down clearly outweighs up. This can be a million things, from a bad feeling in your gut to the onset of a storm that wasn’t forecast to arrive until evening. These are easy because they’re black and white.

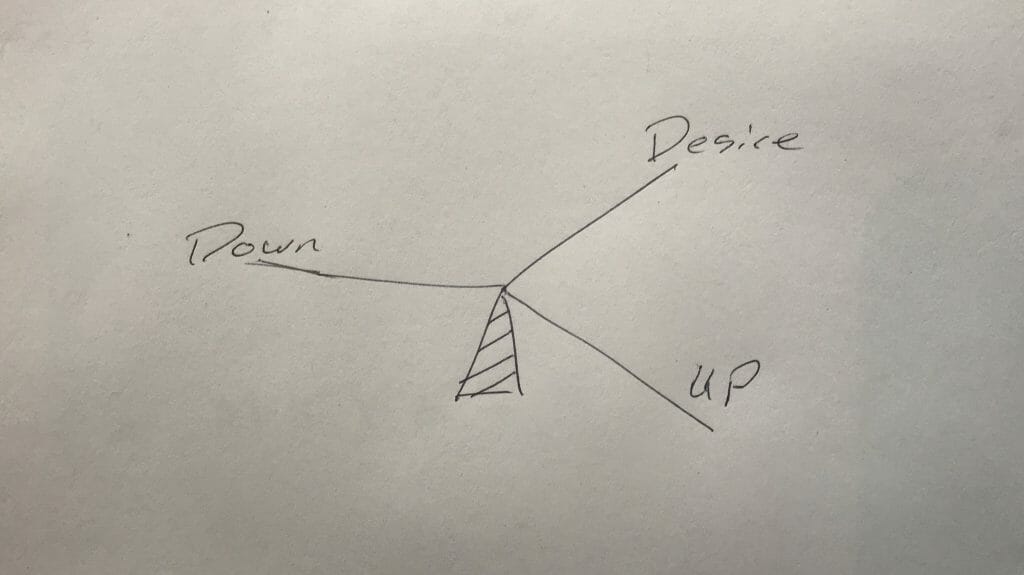

The hard decisions, the tough calls, the most stressful days are when the two nearly balance. One could justify up, and one could justify down. When this happens, the teeter-totter model breaks down. Because it’s not just up vs. down. It’s really been a three-way teeter-totter all along: up, down, and desire.

The ability to neutralize desire depends on your ability to follow Socrates’s advice to Know Thyself. Desire, of course, is tied to emotions. So knowing if you’re angry (and perhaps less risk-averse) or content (more open and contemplative and more risk-averse) will help you know how to take away the bias introduced by the desire side of this three-way teeter-totter.

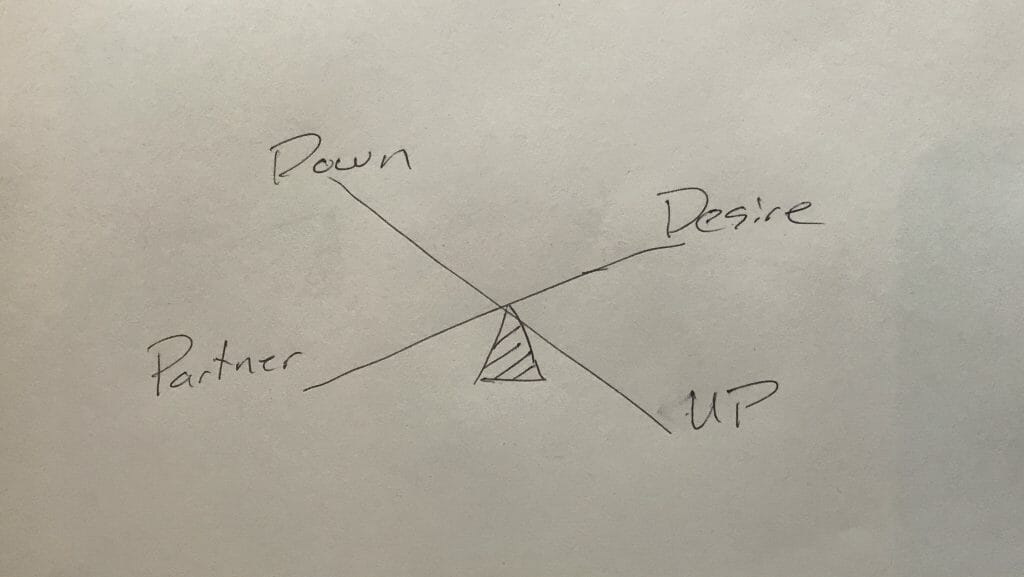

Understand Your Partner: The Four-Way Teeter-Totter

But wait, there’s a fourth arm to this life-or-death decision-making up vs. down teeter-totter analogy, and it’s one you cannot neutralize. It’s your partner (or partners). They have their own internal processes going on, their own contentedness or angst to deal with. Knowing them will help you be more accepting when they argue to go up when you want to go down, or vice versa.

Your partners will have different strengths and weaknesses than you do. In a perfect world, you complement one another. If a team of two feels too frail, especially psychologically, consider adding a third and climbing as a team of three. This may be more complicated logistically, but it’s often just what you need to have the collective confidence, and the collective bag of climbing (running/skiing) tricks, to have an honest shot at success.

Partnerships take time, years, a lifetime. My climbing partnerships have been some of the most important relationships in my life: My Uphill Athlete co-founder Scott Johnston was a climbing/skiing partner before he began to coach me in 2000/2001. Vince Anderson, with whom I climbed a lot in Canada and the Himalaya and with whom I still climb and ski in Colorado, shares the ups and downs of parenting young boys. And we co-own/operate a guide service. Keep an open dialogue and don’t expect to know a partner after a single climb, a single week, or even a single year.

This brings us to:

Take Your Time

Mountain pursuits—alpinism especially—are more practice than sport. The exceedingly complex and dangerous mountain environment demands that we divorce desire from decision-making. It is essential that you keep the up/down/desire/partner arms of the teeter-totter in balance, and that you view success in the long-term as survival.

Process means more than that: it means daily practice. We get up every day and try to polish our climb-gem, our run-gem, our life-gem just a little bit. Days of polishing, years of polishing, a lifetime of polishing, and you reveal something truly unique, truly beautiful, truly yours. Of course it was always there, but without the polishing it couldn’t be seen.

Don’t rush the process, whether it be improving as an athlete or knowing yourself and your partners. Take your time. You won’t succeed at rushing it, even if you try, so let it come at its natural pace. This advice is easy or hard to hear and understand depending on which season of life you’re in. The young and the old don’t like to hear this. The middle-aged tend to see it clearly.

Perfect Preparation for Alpinism: Cover All Your Bases

When it comes to alpine climbing, there is a long list of things you can do to prepare perfectly. We could easily come up with a similar list for skiing or mountain running.

Study the face.

Do the approach and look at the face, take photos to study later, and bring a pair of binoculars. The operative verb here: study.

Alpinists, remember one simple rule: ice is gray, snow is white.

Too many people convince themselves that the “white streaks” are climbable. They’re not. Gray ice can be really hard to see when the rock is also gray, which it usually is.

Get up close.

Touch the face, touch the rock, touch the ice. Find the first pitch so you’ll recognize it in the dark. Time how long it takes you to get to the base.

Climb something similar.

Climb easier and lower-commitment routes that are of similar aspect and elevation (and therefore have similar conditions) before launching big. This can be done in marginal weather if you’re waiting for a bigger window.

Scout the descent.

Identify the hazards that exist on the descent. Can you avoid rockfall hazard by planning to descend at night, or after a planned bivy early in the morning? Think long term, and think survival. Bivy gear is heavy, but losing your life is heavier.

Make a navigation plan.

I always carry way more navigation equipment than anyone expects me to and it’s saved my life numerous times. I always carry: a paper map, a simple/light compass, a barometric altimeter, a GPS, and extra batteries. When it comes to navigation, your contingencies need contingencies. Things go wrong, and navigating in bad weather and at night is really hard—and the consequences of walking off a cornice, rapping down the wrong gully, etc. are really bad.

Know the weather, past and present.

The last 21 days (or so) of weather determine the current climbing or skiing conditions. Do you know what that weather was? Make an effort to follow the weather for three weeks before you travel to a new zone to climb or ski. I always spend time trying to understand the past weather before worrying about the next three to five days of forecasted weather. A good way to understand conditions is to talk to an active local.

Be Cognizant of the Unknown

What you don’t know will kill you.

The mountain environment is simply too complex for you to know everything about it. It’s too dynamic. But the things you don’t know are also the things that are most likely to kill you. So name them, call them out. Cornices: don’t know how big they are but know they’re there. Snowfield halfway up: don’t know how stable that snow slope is, but better allow time to do a check and evaluate its stability. Anchors: don’t know where to set up the belays, so budget time to find the best spot. And maybe bringing those extra two pitons is worth the weight given the unknowns. The list goes on.

To claim knowledge of what you think you know, you must be able to explain why. Why do you think the slope is safe? Explain it to your partner. Why do you think the ice is well-bonded to the rock on that crux section? Explain it to your partner. If you can’t do this, that’s a signal to take a more exploratory approach. Meaning dip your toe in, don’t jump straight in. Place extra gear and carefully tap on the ice very gently, with the side of the tool, to hear it, feel it. Don’t run up to it, runout, and swing in carelessly. Be mindful of the risk of your individual actions.

Have this discussion with you partner constantly. It usually is quite quick, but say it out loud. You’ll be safer for it.

Rescue and Communications

Tell someone where you’re going and when you’ll be back. Furthermore, I believe it is now our responsibility to carry a rescue communications device. These days, no matter how remote you go, if you disappear, someone will come looking for you. Don’t needlessly put search and rescue personnel at risk by being invisible. Make their jobs as easy as possible. Yes, it costs money and adds grams to your kit. The Garmin inReach Mini weights 100 grams (3.5 ounces) and costs around $350 plus a subscription. But you’d feel horrible if someone searching for you was injured or killed because they couldn’t easily find you.

Perfect preparation for alpine climbing is hard. It usually takes more time than the actual objective. But it’s worth the effort once you understand that it is a cornerstone of your safety and success in the mountains.

-by Steve House

If you find “Perfect Preparation” and the rest of the Alpine Principles video series helpful, please share with the hashtag #alpineprinciples.

Note for the video: The intro ends at 30 seconds.