A hundred years ago my great-grandfather walked out on my great-grandmother, leaving her with two young children to raise, Jack and Twila. Seventy-five years ago, Jack’s young wife died of cancer, leaving him alone with a 6-month-old son, Don. Don is my father. I was raised by two loving parents and I never thought about loss. Until recently.

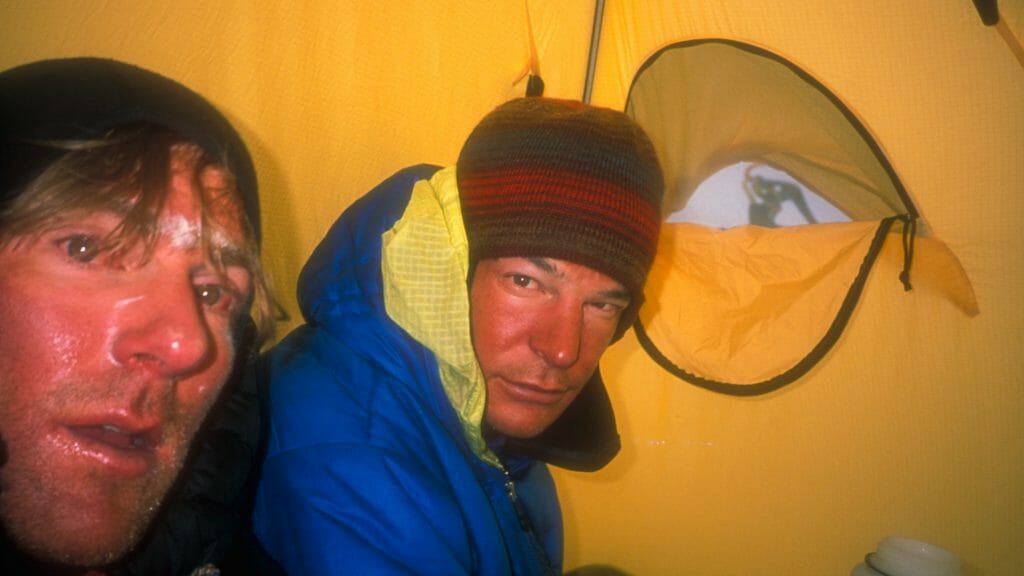

Loss, both tragic and routine, is something I left largely unexamined until a massive climbing fall in 2010. The resulting life-threatening injuries plunged me into a cold bath of self-examination and upheaval. Changes came rapidly: I stepped back from extreme alpinism, began writing about training for climbing, and started a family. Today, as I turn the calendar to 2020, the year of my 50th birthday, I realize how extensively loss and death, facts of every family’s history, have shaped me. Additionally, death is sadly routine within the extended family of alpinists, making loss ever-present in the sport I have dedicated most of my life to.

I see clearly now that my call-and-response relationship with loss has always been at the root of my climbing—the how, the what, and most importantly the why. It is the wellspring of my motivation.

Loss needs movement.

Looking back at my life as an athlete, I am impressed by how much of my impulse to climb, ski, run, and train was reflexive. I would not—could not—survive in a suit (or a suite). My physical need to move, to feel my body moving, is so overwhelming that I cannot keep still. And that need to move is tied to my family’s lineage of loss, a subconscious, unintended passing down of trauma.

The way I imagine it, loss creates scars around love. Both love for others, and for ourselves. Loss, on a generational scale, probably stunted my original ability to bond with other people. To love them, and to love myself. My upbringing taught me to protect myself by not engaging too deeply with the people around me.

Movement loosens the scarring, makes it pliable. Allows it to fade.

Loss causes pain that creates a Pavlovian fear of further loss. Action is the antidote to fear. Movement is the most effective balm for pain.

This connection is so strong that to not move for a few weeks leads me into depression. People who think that working out causes suffering have it backwards.

In her poem “The Uses of Sorrow,” Mary Oliver writes, “Someone I loved once gave me / a box full of darkness. / It took me years to understand / that this, too, was a gift.”

Moving needs measurement.

In an immediate sense this pain provoked in me a need to do something measurable, as if to quantify my worth. I was never a gifted athlete by any stretch. I was a 17:22 5K XC runner on my best day (a very average time that barely bought me a varsity letter in a midsize high school). I used to sit in class burning with impatience to get out in the world and DO something. Something notable. I stayed in the chair because I did not yet know what that would be.

Then I discovered climbing.

Measurement needs achievement.

One of life’s great surprises to me was—and still is—that what I could do in the mountains could be seen as notable. When I learned that the barriers to success in climbing are so high that most don’t get to the route, let alone climb the crux, I began pouring all my energy into climbing. My secret bar for success was garnering a paragraph or two in the Climbs and Expeditions section of the American Alpine Journal. And this became a measure of my worth each year. To not achieve a climb that was journal-worthy was a failure. The whole year.

Loss, or more specifically the misunderstanding of how to deal with loss, or even more precisely how to work with the emotional scars that loss created (and thereby not experience further depression), led me to this arbitrary measure of self-worth. Loss stirred in me a need to achieve something. I built on the first something where I found success.

Achievement needs progress, and progress needs process.

This need to achieve bold new climbs led organically to a quest for progress, which pushed me towards a process. That process, from the ages of 18 to 30, meant climbing and skiing. That’s it. I never trained. Instead, I exercised. Mostly I did random and ridiculous numbers of pull-ups.

Process needs method.

“Process” became training only as a response to the eventual realization that I was not as good as the best in the world. And I wanted—needed—to be as good as the best in the world so that I could continue to achieve. Training was the obvious method to improvement, and my first productive experience with training was with Scott Johnston as my coach, in 2001.

Scott was the method to my madness. And Uphill Athlete, this movement we later created together, is our tool for sharing proven training knowledge. We make no attempt whatsoever to motivate you. In fact, one of our slogans is “You can’t coach desire.”

We avoid the topic of motivation because motivation must come from within you. Motivation imposed from the outside is hollow; false.

Method needs knowledge.

Training requires training knowledge. But in a very real sense, the most important work happens in the space that loss carves out, and the way we fill it up. The pain of loss invites self-awareness and self-examination, which make us better the more we indulge those impulses.

Every day I experience the direct link between loss in my past, present, and future and my need to move. My family feels it too. My sons are both energetic to the extreme and predisposed to simply push harder when confronted by fatigue. Instinctually they process the trauma of their births in the same way their mother and father process their own losses.

Seeing this, I no longer wonder why we endure loss, both within the sport I love and in the larger constellation of life. I now know that loss and pain and fear all motivate me to action. And in a healthy way when you consider the options. During the nine years since my climbing accident I have thought long and hard about eschewing all climbing and skiing, as I dislike the risks to myself and my family. Yet I don’t like cycling very much. Motorcycles are just as dangerous. Alcohol is a poor choice. Business school seems uninspiring. Activism feels futile. So I keep climbing and skiing, and do them conservatively. Safely.

Loss—or whatever your own unique trauma has been—drives us in ways we don’t often discuss. We bury our pain out of necessity, to raise ourselves up to meet the next dawn. But I think that it is worth excavating this pain. Especially with the tools of running shoes and ice axes. Tools that have shown me that love and loss are the weft and warp of the fabric of our human existence.

This is why I’m here. How about you?

New Year’s Post 2019: The Keys to Consistency: Process and Dopamine

New Year’s Post 2018: Know Thyself

New Year’s Post 2017: Dreams are Not Goals