Using heat exposure to prepare for high altitude may sound illogical, but I used it to take advantage of a process called cross-adaptation. By exposing my body to the stress of the heat, I would theoretically improve my tolerance to another stressor: hypoxia. In May I summited Mount Everest in two weeks door to door—from my home at sea level. My keys to success: hard work and strategic pre-acclimation methods. For five months leading up to the climb, I engaged in consistent, structured training under the guidance of coaches Scott Johnston and Seth Keena-Levin. For three of those months, I spent over half of each day at simulated altitude. I also relaxed in any sauna, steam room, and hot tub I had access to.

Recent studies have investigated the degree to which heat training—and cold exposure—can influence an athlete’s later response to hypoxia. While there is a lot of room for further research, scientists have uncovered a few interesting links between training in a hot environment and performance at altitude.

What Is Cross-Adaptation?

Cross-adaptation refers to the process of exposing your body to one type of environmental stress, such as heat, to promote beneficial adaptations that carry over to other environmental stressors, such as altitude. It’s the idea that a non-specific stress response can facilitate adaptation to multiple stressors.

Hypoxia is one such stressor. Going to altitude shocks your system into adapting to decreased oxygen availability. Your heart races, your breathing becomes more rapid, and over time you produce extra red blood cells in order to deliver more life-giving oxygen to your tissues.

The Cardiovascular Benefits of Heat Training

Heat training can prepare your body for more than just sweltering conditions. Through improved cardiovascular function, it has been shown to enhance blood-flow dynamics and oxygen delivery, which equates to better performance in the heat as well as in hypoxia.

Repeated heat exposure increases your blood plasma volume. Plasma volume expansion improves your heart’s ability to pump oxygenated blood to working muscles. Better cardiovascular delivery of oxygen means your muscles will be able to use more oxygen and thus do more work. Improved efficiency for the win.

Efficiency matters when you’re climbing high: For every 1,000 meters you ascend (above ~2,500 m), your maximal oxygen uptake (VO2max) drops by 5–10 percent.

At the cellular level, heat exposure increases heat shock protein (HSP) expression, a protective mechanism. These HSPs also influence the activity of hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF). Among other roles, HIF triggers angiogenesis, the formation of additional capillary networks, and erythropoiesis, the formation of new red blood cells (RBCs). RBCs contain hemoglobin, which carries oxygen throughout the body. All these changes over time influence how well your body delivers oxygen to its tissues.

Active vs. Passive Heat Training

Most studies to date have examined the benefits of exercising in the heat—active heat acclimation. But if you’re a high-performing athlete who already trains a lot, extra workouts in a hot environment may not be practical. In that case, passive exposure—time in a sauna, hot tub, or steam room—could be preferable.

That is how I incorporated it. After workouts three to five times per week, I spent 20–40 minutes in the sauna at my gym. On trips I soaked in hot tubs and sweated in steam rooms.

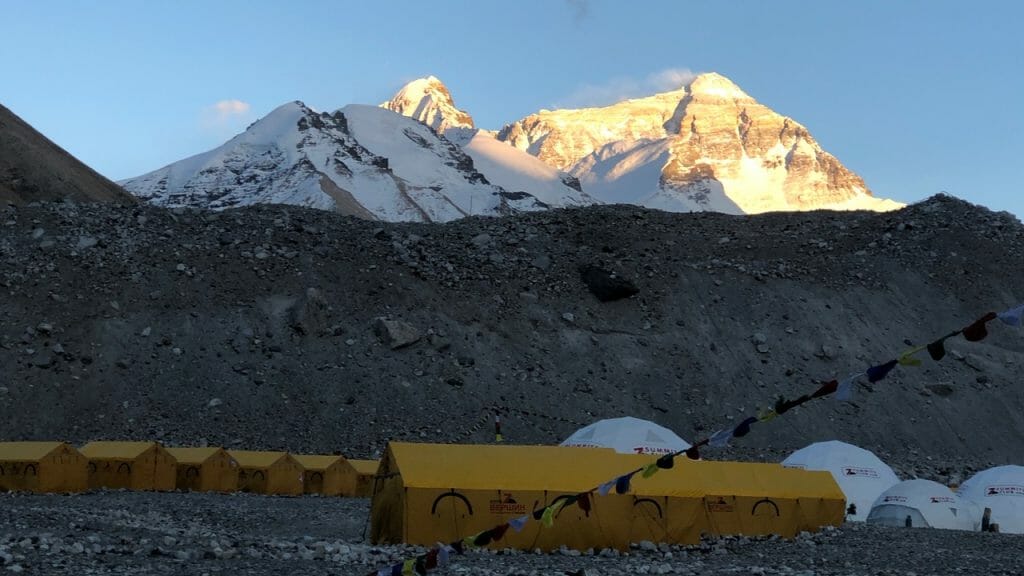

A 2007 study of the effects of post-exercise sauna on a group of six distance runners found that it enhanced their endurance performance, highly correlated with increases in plasma volume and total blood volume. To be fair, I experimented with so much while preparing for Everest that I can’t tease out exactly how well heat exposure worked for me. Anecdotally, I performed really well on the mountain. I didn’t feel any ill effects from the high altitude, even from day one when I arrived at Base Camp, elevation 17,000 feet.

That said, there is no consensus when it comes to the best heat-exposure protocol for cross-adaptation. Passive exposure simply hasn’t been researched as extensively as active exposure.

The Stress of Cold Exposure

The other end of the temperature spectrum may present cross-adaptation opportunities as well. In the case of cold exposure, the primary mechanism appears to be attenuation of the sympathetic nervous system response rather than improved efficiency of the cardiovascular system.

Normally when you’re exposed to a stressor such as cold or hypoxia, your body releases catecholamines like epinephrine, otherwise known as adrenaline. These elevate your heart rate, breathing rate, and metabolism. They put your body on high alert. Studies have found that by repeatedly exposing yourself to cold, you can reduce the effect of this “fight-or-flight” stress response over time.

If you then go to high altitude, the theory is that your lowered sympathetic and metabolic reaction to cold could translate to your body being better able to handle the hypoxic insult—a sort of pre-conditioning for your cells.

With far less research done on this, and limited personal experience with cryotherapy, I can’t say how effective cold exposure might be for a climber looking to pre-acclimate. It’s simply another (chillier) example of potential cross-adaptation.

Heat Exposure and the Uphill Athlete

If you don’t live at elevation, it can be difficult—and expensive—to engage in preparatory training specific to a high-altitude event or climb. There are mask systems for hypoxic training and hypoxic tents and chambers, but this technology isn’t accessible for everyone. Sleeping in a tent can also be a logistical nightmare: You have to be at home every night. Travel is a pain. Your partner might disown you.

An obvious upside of heat exposure is that it’s relatively easy to find a sauna or take a hot bath or hop into a hot tub after a workout, even when you’re traveling. (Submerging yourself in an ice bath is straightforward too, though not nearly as relaxing.) If you live in a hot environment, heat training may already be part of the daily equation.

Think of heat-to-hypoxia cross-adaptation as another tool in the toolbox, something to try if you’re worried about how altitude might affect you. Passive exposure is benign, inexpensive, widely available. The precise benefits may be debatable, but when layered on top of a properly structured training plan, it’s not likely to set you back. If anything, you’ll enjoy the resulting increase in plasma volume. Plus, hanging out in a sauna for a half hour is far from the worst thing in the world.

-by Roxanne Vogel, Nutrition and Performance Research Manager at GU Energy Labs