We are fortunate to live and train in a time when physiology testing is becoming more available and accessible. Either at home or through local labs offering testing services, athletes can better orient themselves and their training by knowing their biomarkers. In endurance training, understanding your metabolism is the key to increased performance, and the test is called the blood lactate test.

While the Gas Exchange Test offered by many physiology labs, if administered correctly, can be held up as the gold standard for determining your metabolic response to exercise, a simpler and cheaper alternative exists. Many labs offer blood lactate testing, and coaches with their own meters can also conduct this test. As you saw in this article, we recently connected Morgan Sjogren with a coach in her area who did this simple test on a hill.

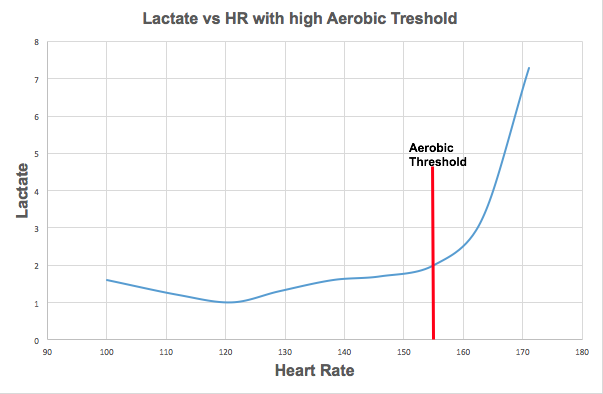

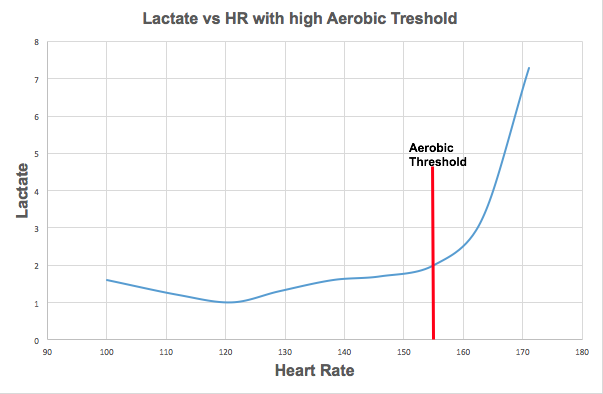

As we’ve already described, blood lactate accumulates when exercise intensity increases to the point where your energy pathways move from mostly aerobic to primarily anaerobic. Suppose you have well-trained aerobic energy pathways and have been building a base (as described in detail in Training for the New Alpinism & Training for the Uphill Athlete). In that case, you have a higher capacity for using lactate as the intensity increases. To put this in context, if you have a high aerobic and lactate threshold, you can run harder for longer than someone who has only trained their anaerobic systems.

The dip we see at a heart rate of 120 indicates that this athlete is moving into zone 2, and their aerobic system is actively converting lactate to pyruvate to sustain the work. As their heart rate and exercise intensity increase, their blood lactate increases gently to the point of their aerobic threshold. As we covered above, once we no longer rely on our aerobic energy pathways, anaerobic glycolysis takes over. This athlete’s energy demands eventually become so high that they exceed their ability to use oxygen to clear out lactate. Since lactate is now leaking out into the blood, it will increase exponentially until the athlete reduces the intensity of their work.

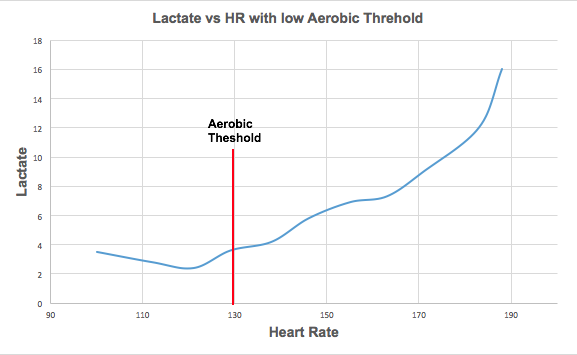

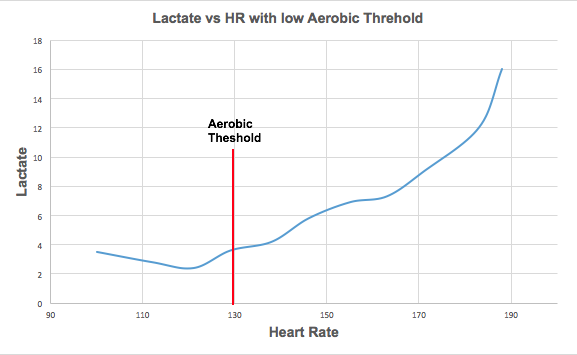

And this is what your graph will look like if you need to build up your aerobic capacity:

As we’ve already described, blood lactate accumulates when exercise intensity increases to the point where your energy pathways move from mostly aerobic to primarily anaerobic. Suppose you have well-trained aerobic energy pathways and have been building a base (as described in detail in Training for the New Alpinism & Training for the Uphill Athlete). In that case, you have a higher capacity for using lactate as the intensity increases. To put this in context, if you have a high aerobic and lactate threshold, you can run harder for longer than someone who has only trained their anaerobic systems.

The dip we see at a heart rate of 120 indicates that this athlete is moving into zone 2, and their aerobic system is actively converting lactate to pyruvate to sustain the work. As their heart rate and exercise intensity increase, their blood lactate increases gently to the point of their aerobic threshold. As we covered above, once we no longer rely on our aerobic energy pathways, anaerobic glycolysis takes over. This athlete’s energy demands eventually become so high that they exceed their ability to use oxygen to clear out lactate. Since lactate is now leaking out into the blood, it will increase exponentially until the athlete reduces the intensity of their work.

And this is what your graph will look like if you need to build up your aerobic capacity:

In contrast to the first graph, this is an example of an athlete who needs to build their aerobic capacity and ability to use lactate for work. We still see the dip at the onset of exercise, indicating this athlete’s aerobic energy systems are up and running, but the rapid increase at a heart rate of 130 shows us that they lack the aerobic infrastructure (mitochondrial, capillary density, oxygen uptake, etc.) for using lactate. As a result, lactate spills into the blood early in the exercise, and this athlete will have to reduce their intensity much sooner.

So you’ve finished your field test and have your numbers – now what? As described in the above graphs, all you need to incorporate blood lactate testing into your training is the heart rate when you reach 2 mMol/L of blood lactate. This is your lactate threshold, which through training, will move, so you will eventually need to re-test to reorient yourself, but happily, our lactate threshold is quite changeable. Unlike some markers of performance that are set by genetics, the lactate threshold is based on your aerobic infrastructure (how well you have been base training) and getting your body used to accumulating lactate at your threshold, between 1-2 mMol/L of blood lactate. Once you exceed 2 mMol/L, you are no longer training at the lactate threshold and will need to reduce the intensity and return to your threshold. The body loves to adapt, and your threshold will move by training at a tolerable level of blood lactate before it affects muscle function.

In contrast to the first graph, this is an example of an athlete who needs to build their aerobic capacity and ability to use lactate for work. We still see the dip at the onset of exercise, indicating this athlete’s aerobic energy systems are up and running, but the rapid increase at a heart rate of 130 shows us that they lack the aerobic infrastructure (mitochondrial, capillary density, oxygen uptake, etc.) for using lactate. As a result, lactate spills into the blood early in the exercise, and this athlete will have to reduce their intensity much sooner.

So you’ve finished your field test and have your numbers – now what? As described in the above graphs, all you need to incorporate blood lactate testing into your training is the heart rate when you reach 2 mMol/L of blood lactate. This is your lactate threshold, which through training, will move, so you will eventually need to re-test to reorient yourself, but happily, our lactate threshold is quite changeable. Unlike some markers of performance that are set by genetics, the lactate threshold is based on your aerobic infrastructure (how well you have been base training) and getting your body used to accumulating lactate at your threshold, between 1-2 mMol/L of blood lactate. Once you exceed 2 mMol/L, you are no longer training at the lactate threshold and will need to reduce the intensity and return to your threshold. The body loves to adapt, and your threshold will move by training at a tolerable level of blood lactate before it affects muscle function.

Happy testing, happy training!

Happy testing, happy training!

Why Blood Lactate Testing?

Measuring lactate concentration in the blood during a graded (stepped) exercise test has been a standby for coaches and athletes ever since portable lactate analyzers hit the market 15 years ago. These handheld devices are the same size and work on similar principles to the much more common glucose meters used by people with diabetes. A tiny blood (almost painless) sample is collected on a test strip that is inserted into the meter. The result will be displayed in 10 to 60 seconds, depending on the meter. By gradually increasing the intensity of the exercise and recording the heart rate when the sample is taken, you can end up with a lactate versus heart rate graph. What does this tell you? Since lactate is a product of glycolytic metabolism and the rate of glycolytic metabolism increases with exercise intensity, lactate can be used as a proxy for intensity. When the lactate concentration in the blood rises 1 mMol/L above the base rate or when the lactate concentration reaches 2 mMol/L, the Aerobic Threshold has been reached. We’ve spent considerable time and ink talking about why all endurance athletes need to know where this point occurs for them. In essence, it defines the upper limit for aerobic base training.Understanding Lactate and the Lactate Threshold

Lactate has often been considered a waste product but is, in fact, recycled by the body for energy or other important molecules during aerobic exercise. At levels below our aerobic and lactate threshold, lactate produced by our working muscles can be oxygenized back into molecules used to sustain the activity. Lactate production only becomes an issue when we exceed our aerobic thresholds. It can no longer be oxygenated or converted to glucose, resulting in a build-up of hydrogen ions and eventually slowing exercise intensity. Blood lactate monitors help us understand when we’ve exceeded our thresholds because the buildup of lactate at the cellular level eventually hits a point when it enters the bloodstream. In the same way we test and set heart rate zones for aerobic training, testing lactate helps us determine where we stand as an athlete and how we get where we want to go. Improvements in the body’s use of lactate largely occur during exercise at lactate threshold intensity. While training above and below this level of intensity can still be beneficial, without knowing where our lactate threshold is, it can be difficult to know how hard to work. Sometimes, we also want to train for adaptations that are above and below our lactate threshold, usually to either increase our aerobic capacity (training below), or our anaerobic pathways (training above). Understanding your lactate threshold can help you or your coach craft a more personalized plan. For example, training at or above your lactate threshold will usually require more recovery. Knowing your threshold can help prevent overtraining and lead to a smoother progression of your fitness and performance.Lab Test

These tests are often given to help athletes determine the ANAEROBIC or Lactate Threshold. The endurance limit is a pace you can sustain for around 45–60 minutes. This is close to a 10K running race pace for a fairly fit athlete. In other words, IT IS HARD! It will help you in your training to know this too, and we like to use a field test to determine it. But what you want to know is the lower or AEROBIC Threshold. The lab tech will likely ask, “Why do you want to know that?” Tell them you want to define your Zone 2 intensity. If you have an option, we’d suggest doing this test fasted (or at least don’t eat a high-carb meal within a couple of hours). Also, make every effort get a 15-minute easy warm-up before beginning the test.Field Test

No fancy lab or treadmill necessary for this, only a moderate hill you can run and walk up, a lactate meter, and a buddy to take the blood samples and record the data. You can self-administer this test but it’s easier with a partner. After your 15-minute warm-up at quite low intensity, begin by walking fast up the hill for 3 minutes. At the top of the hill, your partner will take the blood sample. Then you will walk back down and repeat. Start with a pace that puts your heart rate in the 110–120 range. Each succeeding stage should be done with a heart rate about 7–10 beats higher. It is important to hold the heart rate steady throughout each stage. If you get a bad reading, you should repeat that stage before moving to the next-higher heart rate. Follow the above recommendations for eating and warm-up. In the end you should end up with something that looks like this if you are fit:For a more in-depth review of DIY blood lactate testing, we recommend you check out our comprehensive post on the subject: “Blood Lactate Test Protocol: Tips and Tricks.”

As we’ve already described, blood lactate accumulates when exercise intensity increases to the point where your energy pathways move from mostly aerobic to primarily anaerobic. Suppose you have well-trained aerobic energy pathways and have been building a base (as described in detail in Training for the New Alpinism & Training for the Uphill Athlete). In that case, you have a higher capacity for using lactate as the intensity increases. To put this in context, if you have a high aerobic and lactate threshold, you can run harder for longer than someone who has only trained their anaerobic systems.

The dip we see at a heart rate of 120 indicates that this athlete is moving into zone 2, and their aerobic system is actively converting lactate to pyruvate to sustain the work. As their heart rate and exercise intensity increase, their blood lactate increases gently to the point of their aerobic threshold. As we covered above, once we no longer rely on our aerobic energy pathways, anaerobic glycolysis takes over. This athlete’s energy demands eventually become so high that they exceed their ability to use oxygen to clear out lactate. Since lactate is now leaking out into the blood, it will increase exponentially until the athlete reduces the intensity of their work.

And this is what your graph will look like if you need to build up your aerobic capacity:

As we’ve already described, blood lactate accumulates when exercise intensity increases to the point where your energy pathways move from mostly aerobic to primarily anaerobic. Suppose you have well-trained aerobic energy pathways and have been building a base (as described in detail in Training for the New Alpinism & Training for the Uphill Athlete). In that case, you have a higher capacity for using lactate as the intensity increases. To put this in context, if you have a high aerobic and lactate threshold, you can run harder for longer than someone who has only trained their anaerobic systems.

The dip we see at a heart rate of 120 indicates that this athlete is moving into zone 2, and their aerobic system is actively converting lactate to pyruvate to sustain the work. As their heart rate and exercise intensity increase, their blood lactate increases gently to the point of their aerobic threshold. As we covered above, once we no longer rely on our aerobic energy pathways, anaerobic glycolysis takes over. This athlete’s energy demands eventually become so high that they exceed their ability to use oxygen to clear out lactate. Since lactate is now leaking out into the blood, it will increase exponentially until the athlete reduces the intensity of their work.

And this is what your graph will look like if you need to build up your aerobic capacity:

In contrast to the first graph, this is an example of an athlete who needs to build their aerobic capacity and ability to use lactate for work. We still see the dip at the onset of exercise, indicating this athlete’s aerobic energy systems are up and running, but the rapid increase at a heart rate of 130 shows us that they lack the aerobic infrastructure (mitochondrial, capillary density, oxygen uptake, etc.) for using lactate. As a result, lactate spills into the blood early in the exercise, and this athlete will have to reduce their intensity much sooner.

So you’ve finished your field test and have your numbers – now what? As described in the above graphs, all you need to incorporate blood lactate testing into your training is the heart rate when you reach 2 mMol/L of blood lactate. This is your lactate threshold, which through training, will move, so you will eventually need to re-test to reorient yourself, but happily, our lactate threshold is quite changeable. Unlike some markers of performance that are set by genetics, the lactate threshold is based on your aerobic infrastructure (how well you have been base training) and getting your body used to accumulating lactate at your threshold, between 1-2 mMol/L of blood lactate. Once you exceed 2 mMol/L, you are no longer training at the lactate threshold and will need to reduce the intensity and return to your threshold. The body loves to adapt, and your threshold will move by training at a tolerable level of blood lactate before it affects muscle function.

In contrast to the first graph, this is an example of an athlete who needs to build their aerobic capacity and ability to use lactate for work. We still see the dip at the onset of exercise, indicating this athlete’s aerobic energy systems are up and running, but the rapid increase at a heart rate of 130 shows us that they lack the aerobic infrastructure (mitochondrial, capillary density, oxygen uptake, etc.) for using lactate. As a result, lactate spills into the blood early in the exercise, and this athlete will have to reduce their intensity much sooner.

So you’ve finished your field test and have your numbers – now what? As described in the above graphs, all you need to incorporate blood lactate testing into your training is the heart rate when you reach 2 mMol/L of blood lactate. This is your lactate threshold, which through training, will move, so you will eventually need to re-test to reorient yourself, but happily, our lactate threshold is quite changeable. Unlike some markers of performance that are set by genetics, the lactate threshold is based on your aerobic infrastructure (how well you have been base training) and getting your body used to accumulating lactate at your threshold, between 1-2 mMol/L of blood lactate. Once you exceed 2 mMol/L, you are no longer training at the lactate threshold and will need to reduce the intensity and return to your threshold. The body loves to adapt, and your threshold will move by training at a tolerable level of blood lactate before it affects muscle function.

Some Guidelines for DIY Testing

- For about the cost of two treadmill tests you can own your own meter. You won’t need it often but sharing it with other athletes who want to test for progress every couple of months is an idea worth considering.

- Lactate.com is currently the only source we know of in the US selling meters. They sell the Lactate Plus, which we use, and the Lactate Scout along with the test strips needed. The old Lactate Pro, which we also use and like a lot, has been discontinued. Both meters and test strips are becoming harder to find.

- It is frustratingly common to get error readings when you test a sweat-contaminated sample. This is especially true with the Lactate Plus, which uses a very small blood sample. Wipe the first drop of blood away with alcohol and then dry the area with a dry paper towel. Test the second drop to lessen the chance of errors.

- Climbers often have very calloused fingertips so it can be hard to get samples from their fingers. In that case, we prefer to use earlobes.

Happy testing, happy training!

Happy testing, happy training!