When the shotgun blast echoed throughout the canyon, announcing the end of the 24 hours of climbing, I felt like I still had another hundred pitches in me. I lowered my partner from his final route and we raced back to the Trading Post just in time to turn in our scores.

The 2018 edition of 24 Hours of Horseshoe Hell (24HHH) marked my fourth time competing in the event. The challenge is simple: climb as many pitches at Arkansas’s Horseshoe Canyon Ranch as you can in one day, 10 a.m. Friday to 10 a.m. Saturday. I first heard about it when I moved to Little Rock, Arkansas, after college, and I thought it would be fun to do. I attempted to register, but the system crashed and I abandoned the plan.

Then a little over four years ago, my now-fiancée suggested I go for it again. I had recently started climbing with someone who was just crazy enough to do it with me. In the past, whenever I’d asked any of my regular partners if they’d be interested in climbing for 24 hours, they straight-up laughed at the idea. “No way, dude, that sounds so dumb!” But Nick Semancik was equally gung-ho for it. It’s his mentality to get after it, whatever “it” may be. Finding a good partner for the competition—both of us being equally motivated—was key. We entered in 2015 via a newly instituted lottery system and got in. We named our team All Outta Bubble Gum, a nod to a line from the 1988 cult film They Live: “I came here to chew bubble gum and kick ass, and I’m all outta bubble gum!” Pure action-packed madness follows. It seemed right.

Our first year I climbed 139 pitches. Year two, having requalified by both getting over 100 pitches, we went back and I did 179. Then year three I did 189. This year my goal was to reach 240 pitches. It would mean averaging a daunting 10 pitches per hour.

“How can I train my body to go for 24 hours?” This was my primary question for Scott Johnston during our phone consult two months before Horseshoe Hell. I’d been reading Training for the New Alpinism, and it had become clear to me that I needed to improve my overall endurance. Nick and I felt good on our strategy and systems, but this year I wanted to avoid the energy crash that always seemed to hit around 3 or 4 in the morning.

Also, a bad fall had temporarily derailed my training. It had happened during an outdoor session in mid-July: the rope went through my belayer’s Grigri and I dropped 15 feet to the ground, landing on my butt. I was backboarded down by Rocky Mountain Rescue, and at the ER I was told I’d broken my sacrum. Three days later, another X-ray showed that I’d only bruised my coccyx. My friends joke that I must have a butt made of steel. I was on crutches for five days, and it was about 20 days to where I could hike again without pain. The injury and my recovery served as additional motivation to seek out Scott’s wisdom.

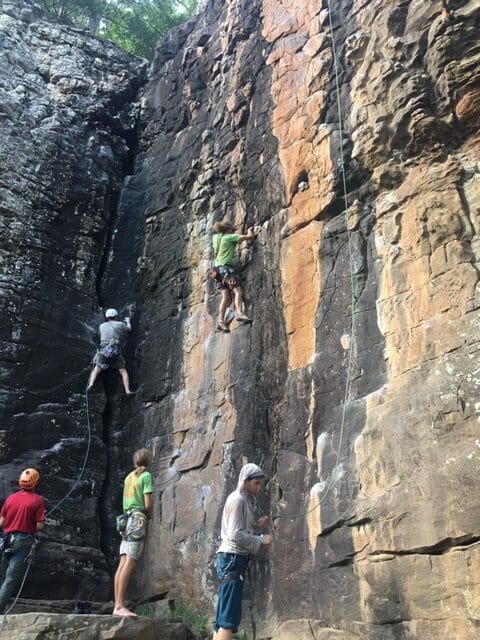

Rehearsing some 5.10s two days before the competition.

Scott advised me to stop mountain biking and instead double down on hiking uphill and climbing. I was living near Estes Park, Colorado, for the summer, and most mornings before breakfast I’d hike up a trail right out my front door that ascended 400 feet in three-quarters of a mile. I tried to do it a little faster each time. Some days I’d do a 500-foot multipitch route close to home over and over, and other days I’d scramble up a 600-foot third-class gully to simulate moderate climbing. I supplemented this aerobic work with many hours in the climbing gym.

I started capping my climbing sessions with Scott’s Killer Core Routine rather than a beer. Training went from being a burden to a lifestyle choice.

Scott also suggested adjusting my diet to encourage fat adaptation. I ended up going full keto instead, dropping carbs completely. I lost about 15 pounds, which helped me during the competition, just being at that fighting weight. I started capping my climbing sessions with Scott’s Killer Core Routine rather than a beer. Training went from being a burden to a lifestyle choice.

I arrived in Arkansas at the end of September feeling stronger than in previous years. Nick and I got everything ready for our long day of climbing: we carried our gear to the area where we wanted to start, and we cached water and food throughout the canyon.

James dashes up The Greatest Show on Earth (5.8) in the North Forty around 2 p.m.

There are about 400 single-pitch sport and trad routes at Horseshoe Canyon Ranch, most in the 5.6–5.9 range. It’s a moderate-climbing mecca. During the competition, you and your partner have to lead everything, and you have to lead it clean. No pulling on gear, no taking, no falling. You can do each route twice. The key to doing well is to keep climbing, to never wait in line. Nick and I devised an efficient system: we cut our rope to 25 meters, and we would “tie in” with a locking carabiner and pull the rope through every time, never having to untie a knot. There would be leaver ’biners at all the anchors, so we’d never have to clean a climb. Along with quickdraws, we would carry a single rack and a few slings to take advantage of the less popular trad routes.

As kickoff approached, climbers and spectators gathered in a colorful, eclectic mass at the Trading Post. Jeremy Collins, the climbing artist and a longtime 24HHH competitor, launched into his annual Climbers’ Creed: “Find your partner and face them. Look deep into their souls. Raise your right hand. Repeat after me.” The psych built as we laughed and shouted the lines. “We are more than climbers! We are warriors! We are lions in a field of lions!” At the shotgun blast we all took off running. In that moment, it’s fun to see who knows the game and who doesn’t—who’s carrying their gear up to the crag, who’s sprinting like us to where they’ve already stashed it. Nick and I quickly covered the half mile to the cliff and our first route. The excitement was infectious, everyone hopping on climbs and whooping it up. You get motivation from being around so many people, so much energy.

We avoided the lines and swiftly racked up routes. We were climbing so fast that often Nick would be halfway up the wall by the time I had him on belay. It was really fun to be moving at that level hour after hour. I don’t advocate free soloing, but when in Hell, I bend my personal rules in order to climb fast—skipping bolts, running out trad routes, my level of focus 100 percent in the moment. Nothing else is on my mind during those 24 hours but climbing.

At the same time, I love that not everyone takes the climbing super seriously. People are dressed up in goofy costumes, joking around, playing music, boosting morale. There are dozens of spectators knocking back beers and cheering, occasionally heckling. Most climbers are out there to have a good time. Then there are the more competitive folks like me and Nick, who are also having a blast, just with a hard-charging approach. The scene, the diversity of the climbing crowd, is a major highlight of the event.

Aside from a nutritional hiccup around midnight, when I ate a gel that disagreed with my stomach, I never lost energy. We blared electronic dance music to keep us going in the early morning, that pre-dawn hour when most people are fading and antsy for the sun to come up. After sunrise we ramped up our pace again, anxious to get more pitches in, even as other climbers started trickling down from the crag. Nick was on the wall during the 10 a.m. shotgun blast on Saturday. We had to run to get back to the Trading Post within the final 15-minute window. For the first time I was upset that the 24 hours was up. It wasn’t that I’d come short of 240 pitches. It was that I could have easily continued to climb.

Nick and James at the Buffalo River after the competition, happy as can be and laughing at war wounds.

I finished with 201 pitches, one of only four people in the competition to get over 200 routes. It was a record-shattering year, with Ardian Prishtina beating Alex Honnold’s previous Individual Score record for points and Jeremy Collins setting the new Individual Route record with 299 pitches. Nick upped his game, too, climbing 17 more routes than in 2017: our combined 367 routes placed us third in the Team Routes category.

This was hands-down the greatest athletic performance of my life. My trophy is the current condition of my body and my motivation to continue to train toward my next big climbing goal, whatever that may be. Who knows, maybe Nick and I will return for a fifth 24HHH. This was supposed to be our last year, but I had so much fun and felt so great that I’m inspired to consider another go—perhaps with a trad route twist.

-by Uphill Athlete James Wieman