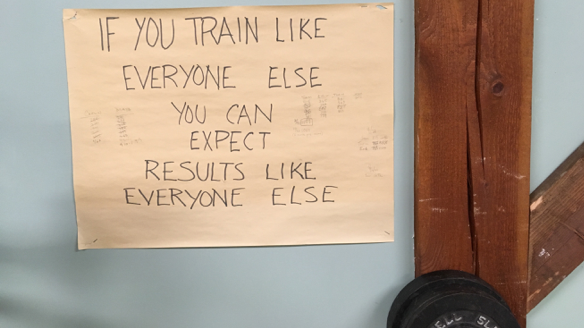

I’ve had an old, yellowed, hand-lettered sign posted in my gym for about 15 years. It reads, “If you train like everyone else you can expect results like everyone else.” Those words—an invitation to think outside the box—have shaped my approach to coaching for longer than that sign has hung there. Training outside the box is a philosophy that encourages curiosity and creativity, and without it there would be no Training for the New Alpinism. There would be no Uphill Athlete.

I have trained for a range of endurance sports at a high level myself—swimming, cross-country skiing, alpine climbing—and I have coached elite cross-country skiers, skimo racers, alpinists, and mountain runners. Throughout it all, my guiding principle has been to try new things. To challenge the status quo. This started years ago when I experimented with novel approaches to my own training. The successes and failures—especially the failures—of those N-of-1 studies gave me new insights into how an alpinist like Steve House could improve his performance in the mountains. Our collaboration on his training formed the basis for Training for the New Alpinism, and eventually the larger Uphill Athlete enterprise: we had learned so much together, and we were motivated to share it.

Training Outside the Box: Curiosity and Experimentation

I often look at the ways in which coaches in similar sports have successfully trained their athletes. Back when I was coaching Steve, I was also working with high-level cross-country skiers. Applying methods used to train 800-meter runners to skiers who specialized in the sprint event led to some significant success.

As diverse as the range of sports from which Steve and I have drawn inspiration is, we’ve hewed to one simple concept: look for the common physiologic demands shared by what seem to be vastly different events. The trial-and-error quest to uncover these gems can be frustrating at times, but each new discovery keeps us going.

Nowhere in our book, on this website, or in talks I give do I pretend to have invented anything new. I’ve merely taken well-tested training methods and innovated and adapted these existing ideas to new and less conventional athletic events. There really is nothing completely new when it comes to athletic training.

The Problem: Controlling for Speed in Mountain Athletics

One of the challenges in training for sports like cross-country skiing, skimo, and mountain running is that race course profiles are not uniform, and athletes normally train on that same steep or rolling terrain. As a result, coaches and athletes lack control of the most crucial element: speed.

This all-important variable allows road and track runners and swimmers to progress their training in a systematic, controlled way while monitoring for improvement or, more importantly, lack of improvement. If the training we are applying is not making the skier or mountain runner faster, we’d want to change it, right? But if we have no good way of measuring speed or its improvement, all we can do is hope that a bunch of hard training will translate into a faster athlete. Going out and running hard up and down a hill may make you fitter, but will it make you faster? Awards in races are not given to the fittest or those who can do the hardest workouts. The awards go to the fastest.

Getting Creative: Combining an Incline Trainer with a SkiErg

In order to take some of the guesswork out of race training for these mountain sports, where it’s difficult to isolate for speed, we’ve had to get a little creative. To that end, we designed a progression of specialized workouts on a setup that combines an incline trainer with a Concept2 SkiErg. These workouts gradually take the athlete from his or her current status to a new level of performance over the course of many weeks, with small enough increments in increased load that the athlete can adapt and we can be sure we’re making targeted progress.

Incline trainers, which are treadmills that go beyond the typical 15 percent maximum gradient, can reach grades of 40 percent—in other words, a crazy steep hill. They are not too rare in commercial and even some home gyms. Likewise, the Concept2 SkiErg is also becoming a fixture in many gyms. By combining these two powerful training tools, we can simulate steep uphill skiing and have the athlete do interval training in a very controlled setting. Not only does this allow careful monitoring of, and control over, speed and intensity, two of the most important variables in an interval workout, but even more importantly it allows us to measure the athlete’s progress (or lack thereof). In other words, is she getting faster as a result of the training?

The Principal Advantage: Isolating Variables

This method imposes a level of artificiality to the training that I understand many will balk at. Admittedly this training is not for everyone and it does not perfectly mimic the conditions of the race. Its principal advantage lies in that it eliminates a number of uncontrollable elements, instead focusing the training session on improving one or a handful of crucial qualities.

With a simple setup like the one shown in the following short video, we can control and monitor such variables as speed, grade, heart rate, vertical distance climbed, and even blood lactate, all of which allow us to monitor the athlete’s improvement in ensuing sessions. We can build progressive workouts that build upon previous ones. This particular workout, done at a 25 percent grade, was 30 minutes of 30 seconds on/30 seconds off done at maximum sustainable effort. This is a race-paced aerobic endurance workout for a high-level athlete, and is just one example of a workout. We use different types of workouts to produce different training effects.

Uphill Athlete Coach Maya Seckinger trains on a TreadSki for her upcoming racing season.

Keeping an Open Mind

Keep an open mind as you look for ways to improve. For the recreational athlete, aim first for the lowest-hanging fruit. But for the elite-level athlete, be willing to think outside the box, as we have done here with the incline trainer and SkiErg. The higher the level of the athlete, the more creative the coach and athlete may need to be in order to effect improvements. Just doing more of what you’ve always done is not likely to yield good results. Good results come from experimenting and refining, from daring to approach your training a little differently.

This article was originally published by Scott Johnston.