Ever since we began getting emails in response to Training for the New Alpinism, there is one question in particular that has come up more than any other. Mountain athletes want to know how to find a balance between conventional responsibilities such as work, family, or school and their desire to be in the mountains. Some people are constrained by location, some by energy, and others by time. Regardless of the individual situation, these inquiries tend to share one thing in common: they usually come from folks who want to cram a week’s worth of activity into one or two days. And they also want to improve in their discipline.

There’s nothing wrong with being a weekend warrior, per se. For many, it is simply the only way to stay sane. That said, we cannot accurately call it training. True training requires a much more regimented approach to how we exercise. Rather than subjecting our bodies to these boom-and-bust cycles of activity, we need to find a more stable balance if we ever hope to see meaningful progress in our strength, stamina, or overall fitness.

Homeostasis and the Training Effect

In a healthy human body, the chemical concentrations of an array of hormones, enzymes, and electrolytes, along with the physical properties of heart rate, temperature, and blood pressure within the tissues, are in a state of balance physiologists refer to as homeostasis. A stress applied to the body, by definition, disturbs this state of equilibrium.

Hans Selye—the father of stress research—was the first to study the effects of stress on living organisms. He differentiated between good and bad stress, and developed the “General Adaptation Syndrome”: a three-stage synopsis of the body’s short- and long-term response to stress. Modern sports training theory is founded upon his work.

How the Body Responds to Stress

Consider a stress almost all of us have experienced: the cold virus. The disturbance the cold virus introduces to our delicate homeostasis causes a strong reaction by the immune system and we become sick. The reason that we feel weak and run down is that the body spends considerable energy trying to restore homeostasis while fighting the invading virus.

Similarly, when we climb, run, or lift weights, we subject the body to a stress (albeit more benign), known as a training stimulus. This stress temporarily pushes some of the body’s systems slightly out of homeostasis, which is why you may feel tired, stiff, or sore the day after a hard workout. Just like when you’re sick, your body is trying to return to homeostasis.

We all know that exposure to the cold virus can help the body develop immunological resistance to that particular virus. What coaches and athletes have long known is that the same phenomenon holds true for training. Repeated small stressors in the form of training stimuli cause the body to adapt to that particular stress, so that subsequent similar training bouts cause less disturbance of the homeostasis.

Chronic vs. Acute Stress

So it’s clear that stress is actually a good thing for strengthening the body. As Selye noted, “Man should not try to avoid stress any more than he would shun food, love or exercise.” That said, the question of what kind of stress needs to be addressed. Obviously, not all stress is good stress.

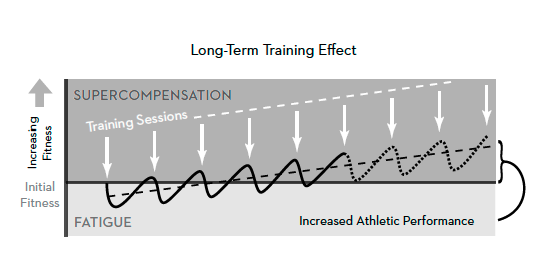

In short, there’s a major difference between good and bad stress when it comes to strengthening the body. Good stress, or chronic stress (frequent, small, progressive), occurs when systematic training stimuli cause positive adaptations, brought about by the body’s ability to restore a new and more robust state of homeostasis. This is known as the training effect.

Conversely, bad stress, or acute stress (infrequent, large, excessive), is any stress that greatly exceeds the body’s capacity for work, and thus disturbs homeostasis too much, and too seldom, to foster effective adaptation. This is why, in the long run, acute stress is shown to have a negative effect on fitness.

This distinction between good (chronic) stress, and bad (acute) stress is, in a nutshell, the basis for all modern sports training theory.

The Weakened Warrior Syndrome

As we explained earlier, there is nothing wrong with being a weekend warrior. Perhaps you are driven not by fitness and health, but by adventure, time in the mountains, or simply by fun. By all means get out there and enjoy your time. If this means only getting out on a weekend, then so be it.

But if you would like to bring your fittest, healthiest, best-trained self to those weekend adventures, it can’t be overstated how important a more regular training regimen is. You can’t spend all week simply dreaming about the 14er you want to climb that weekend, then go out and hammer yourself into a mass of jelly on the outing, and also expect to make significant, long-term gains in fitness. For that, you have to incorporate structured training throughout the week.

The Value of Training during the Week

There’s a wealth of good research on the connection between exercise and happiness. As sports and exercise psychologist Kip Matthews, PhD, notes, “The less active we become, the more challenged we are in dealing with stress.” Going for a run before or after a hard day at the office may not sound very enticing, but it’s actually one of the best things you can do to manage the stress that accumulates throughout the workweek.

The good news is that training does not have to be boring, loathsome, or one more annoying item on your weekly to-do list. With just a modicum of creativity, it can help to replicate some of the feelings of satisfaction and contentment that we get from those epic weekend adventures, which is part of what draws us to mountains in the first place. And even though alpenglow is not included, the fact is even a modestly structured approach to training will have a huge payoff—not just physically, but emotionally and psychologically as well.