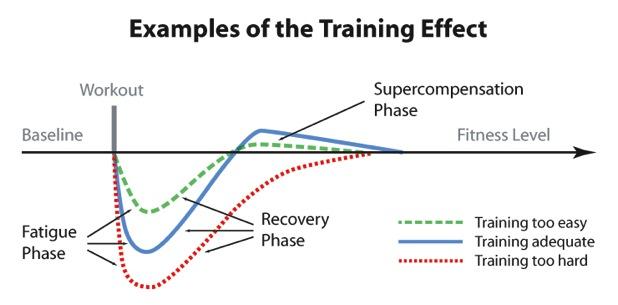

Training makes you weaker- it is through recovery that you get stronger.

That very simple concept is set in bold because it is often poorly understood across the full spectrum of sports training. Put another way, the hours to days following a workout are when your body responds to the training and adapts to better handle similar loads in the future. It should then come as no surprise that what you do following a training session can impact your body’s response to it. From practicing yoga to eating well to integrating self-massage, there are many strategies that can facilitate a faster recovery—day to day, week to week, and season to season.

The Training Effect: Why Recovery Is Important

In the time following a training session, which can range from an hour to several days, a cascade of physiological effects trigger adaptations in your skeletal and cardiac muscles, as well as in your biochemistry. The fatigue you feel signals these subcellular events, which result in the training effect. Muscle damage and depleted energy stores—most endurance athletes’ constant companions—are also the two most powerful training stimuli. Essentially, being fatigued is teaching your body to handle increased training loads. And because training for endurance requires that you exceed your current work capacity in your workouts, endurance athletes labor under persistent fatigue.

In order to improve, you must drive yourself into a state of fatigue.

But if the point of recovery is to prepare you to do more training, how do you know when you are sufficiently recovered and ready for the next training session? The “Recovery by Feel” episode of the Uphill Athlete Podcast delves into our best thinking on this subject; we recommend taking a listen.

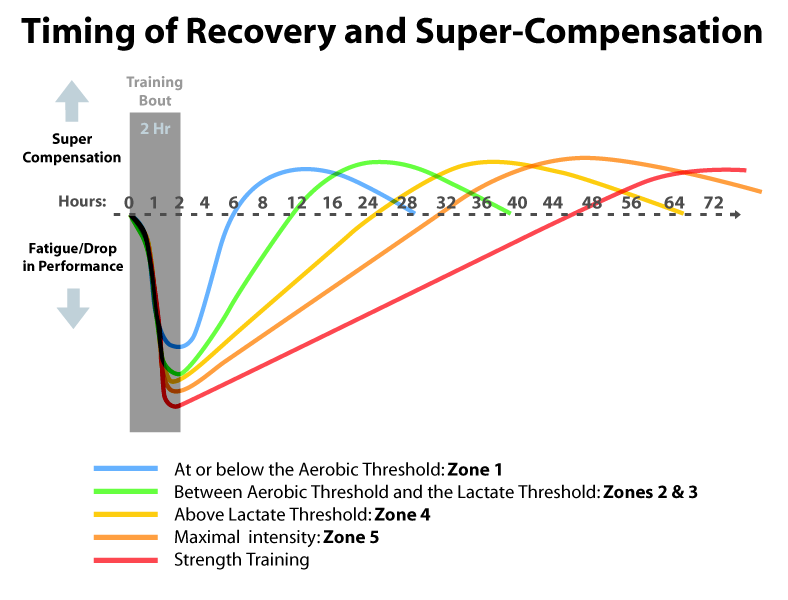

A general rule is the more intense the training session (the more it relies on fast twitch muscle fibers), the longer the recovery time. Uphill Athlete training involves a mix of intensities, thus stimulating a variety of adaptations that you recover from/adapt to at different rates. The aerobic system recovers much faster, which is why very easy aerobic work can be an ideal thing to do following intense sessions (see “Active Recovery Workouts,” below).

The following graphic, courtesy of Jan Olbrecht, shows in a more quantitative way the rate of recovery from various types of training sessions.

Training requires many hundreds and even thousands of repetitive movements. Lack of recovery—rather than too much training—is often the cause of poor to no adaptation.

By now it should be clear that fatigue without recovery will derail your training goals. Adaptation, which happens during recovery and NOT during training, is the body’s way of preparing for the next workout. If you don’t recover properly, you diminish the work capacity you can take on in your next workout, hence diminishing the returns you can get from the training effect of that workout. So, the flipside is also true.

In order to improve, you must drive yourself into a state of recovery.

Key Components of Recovery from Training

If your idea of post-workout recovery is flopping onto the couch with a beer and chips or dashing into and out of the shower before racing off to work, you may want to reconsider your approach. Adequate sleep, proper nutrition, and active or passive recovery are crucial to the recovery and adaptation process. Chances are that you take the improvement of your performance in your chosen sport pretty seriously and want to maximize the gains from your training. If that describes you, make sure to take advantage of appropriate recovery essentials too.

Sleep

The most important and most underused tool for recovery is sleep, especially deep sleep known as SWS (short wave) sleep. During REM sleep, your endocrine system is busy releasing several anabolic (growth) hormones. One of these growth hormones, GH1, is the body’s primary signaling agent for adapting to higher training loads. If you aren’t getting enough SWS sleep, your GH1 levels will be significantly reduced and your recovery will be impaired. We have all experienced how a poor night of sleep affects us. Naps are a staple of elite athletes to ensure they get enough SW sleep. Even a 20-minute nap can do wonders.

Nutrition and Hydration

Refueling is critical to recovery, especially within 30 minutes of your workout. Missing this window after training can extend your recovery time by days. It is during this half-hour span that your muscles are most receptive to replenishing depleted glycogen stores. Training even in Zones 1 and 2 will result in glycogen depletion, especially if the duration exceeds an hour. It is advisable to take in 200–300 calories of low-glycemic carbohydrates at some point during this crucial window. Mixing in protein and fat is not a bad thing, but it is really the glycogen stores you should aim to restore immediately after a workout. A simple way to do this is to have a recovery drink or premade snack available at the end of your training session.

Adequate hydration is also important, especially if you are training in heat or for extended periods of time. For most athletes, there are really only two ways to monitor hydration status: urine color/quantity and body mass pre- and post-training. Weighing yourself before and after an endurance training session will give you a good idea of how much water you have lost through breathing and sweat. If you have the discipline and can carry your bathroom scale to the trailhead, this works great. A simpler but less precise test is the color of your urine in the morning. Darker urine means you are poorly hydrated. Frequency of urination is another simple test. If you’ve been out running around in the mountains for much of the day and have not had to stop and pee, you are probably dehydrated.

For more information on good nutrition, check out out article on putting foundational nutrition into practice.

Self-Myofascial Massage with a Foam Roller, Ball, or Stick

If you are pushing your body’s capacity for work, training will take a toll—several tolls, actually. There are two pathways by which a heavy training load can result in too much muscle tension:

- When your sympathetic (fight-or-flight) nervous system is consistently aroused, overpowering your parasympathetic (rest and digest) nervous system, your muscles can’t fully relax.

- When adhesions, knots, and trigger points form in the heavily used myofascial system, these muscles can no longer fully stretch or contract; this leads to impaired function.

Self-massage is a cheap and easy thing you can do every day to speed up recovery. When your muscles are tight or sore, you are experiencing acute inflammation. Although inflammation is an important signal to trigger the cascade of adaptation processes, too much inflammation will result in stiff and tired muscles. That lack of mobility, in turn, will impact your ability to train. While your hands are great for self-massage, some areas are nearly impossible to access. Because of that we recommend investing in a few self-massage tools: foam rollers, sticks, and balls, all of which serve the purpose of working out knots and increasing blood flow to tired muscles.

Self-massage allows you to control the depth and pressure of the massage. In general, if the rolling is very painful, you need to do more of it; but like anything else, too much of a good thing can be a problem. You can bruise the muscle, which delays its recovery. It’s better to do just a few minutes of rolling on an area—and to do it often. In other words, two to three 10-minute rolling sessions per day are more beneficial than a marathon session twice a week.

A healthy muscle should be able to withstand a good deal of pressure with no pain. In contrast, an inflamed muscle in spasm can be very painful even to a light touch. Give some different muscles on your body a good press or squeeze: notice that the ones that are loose don’t hurt when you press on them while others that feel tight may be quite painful under a similar amount of pressure.

Having a small arsenal of inexpensive rolling tools will allow you to do your own maintenance sessions. From top to bottom, the following images show a simple, smooth foam roller (knobby ones work well too); a rolling stick that allows concentrated pressure; and our all-time favorite tool: the MobilityWOD ball by Rogue Fitness. We recommend that you make this little self-torture device an integral part of your daily routine. (Uphill Athlete has no affiliation with Rogue; though we are fans of this ball.)

If you really want to dive into the self-massage/myofascial release world, check out Therapy Balls, sold by Tune Up Fitness, along with the beautifully illustrated 400-page companion book The Roll Model, by Jill Miller. The book goes into great depth on the various methods of using the balls, all of which are photographed and paired with detailed explanations of what they do and when best to use them.

Both the Rogue Fitness and Therapy Balls are small, making them easy to travel with. You can even use them while sitting on an airplane!

For less than the cost of one good deep-tissue massage, you can be fully outfitted with a range of very helpful self-care and recovery tools.

Yoga

Yoga is one of the most popular recovery tools for athletes. It combines gentle stretching with relaxation. Your sympathetic (fight-or-flight) nervous system gets jacked up during training and can stay in an elevated state for long after a workout. This lengthens the recovery time. Yoga has a profound effect on the parasympathetic nervous system, which brings you back to a more balanced condition, enabling recovery. We at Uphill Athlete have developed our own recovery-focused yoga program targeting athletes. It has received great reviews, and we encourage you to use it frequently.

Active Recovery Workouts

Working out to aid recovery may seem like a contradiction in terms, but proper recovery workouts have real benefits. Active recovery is not a workout for increasing fitness. It is a light session to speed recovery so that you can get back to capacity building as soon as possible. You should feel better at the end of this session than you did at the beginning.

Broadly speaking, dedicated recovery sessions fall into one of two buckets: an active/structural option and a more passive/rest-day option. The former is what we’ll hit on here, while the latter simply involves taking a day off from training to completely rest and recover.

The “active” component of active recovery is important. What we’ve noticed over the years is that if athletes take an entire day off after a hard training session, they tend to come back sore, lethargic, or less than optimal. Integrating some element of movement into a dedicated training session, however, often leaves athletes feeling fresh and loose.

There is a fine line between effective movement and excessive movement. Instagram abounds with posts of athletes doing high-intensity rowing intervals on their “active recovery” day and finishing on their backs in a puddle of sweat. This is not active recovery. On the flip side, many online programs will sell the idea of a 60-to-90-minute steady state run as an active recovery session. Unless you are a distance-trained athlete doing 100+ miles of total volume a week, 60–90 minutes of running is not an active recovery session. It is an aerobic capacity event, at best, and poor programming, at worst.

With that in mind, here are a few guidelines to keep in mind when planning and executing recovery sessions.

Keep cyclical movements non-impact. Even if you are a well-conditioned runner, recovery runs need to be actually easy effort. Running is a high-impact sport, and piling more impact on legs already feeling beat up is not the answer. If you don’t feel better after a recovery run, try using another nonimpact modality, such as a rower, a SkiErg, a bike, etc… By turning to one of those options, not only are you creating a new stimulus, but you’re also giving your weight-bearing frame a break… even if it’s just for a day. Something as simple as a 20-minute evening walk can be especially effective after a long, hard day in the mountains or after a hard effort or race. Even on days off, the light aerobic stimulation of a very easy swim or bike ride will speed recovery. If swimming is an option for you, take advantage of it. There is something magically therapeutic about water. Over many years and many athletes, we have discovered that swimming—even for nonswimmers—is the most effective recovery workout for loosening up and getting rid of that dead-leg feeling. It’s non-weight-bearing, the water keeps body temps lower, and you’re horizontal so that your heart does not have to work against gravity. An easy few hundred meters of freestyle in a pool, lake, or ocean coupled with some flutter kicking works wonders on heavy legs. For nonswimmers, just hanging on to the side of the pool and flutter kicking for a few minutes can be helpful. Other options are to vigorously tread water or “run” in place in water too deep to stand in.

Don’t be afraid to mix things up to make it fun. For example, instead of rowing for 10 minutes, it can be equally effective to rotate between a 2-minute row and a 2-minute bike for a total of 10 minutes. Just be sure that the overall intensity is very low.

Prioritize breathing. It is important to understand that breathing needs to be a priority during active recovery sessions. Focusing breathing comfortably, for example, helps regulate the intensity of the session. Additionally, focused breathing has been shown to have a phenomenal carryover to the mental side of training (think meditation).

Again, keep the intensity very low. When planning an active recovery session, the emphasis must first be on the recovery. Very low-intensity aerobic work has a powerful restorative effect. If you are pushing the envelope of what your body can absorb, activity recovery sessions should be built into every training week.

Other Recovery Methods

Here are a few other methods that can contribute to your recovery:

Contrast Baths

The old Finnish trick of rolling in the snow right after the sauna can be duplicated even if you have neither snow nor sauna. Taking an ice bath followed immediately by a hot bath or wading into a cold stream at the end of a long run can have the same flushing effect of increasing blood flow in your limbs. These all seem to reduce local inflammation, which is a necessary side effect of training but can be too much if you can’t walk down the stairs the day after a big run.

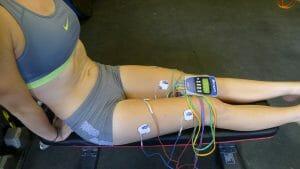

E-Stim

Electrostim machines have gained popularity among professional cyclists who need to recover quickly during multiday races. Special sports versions such as those sold by Compex are effective but expensive. We recommend only using these on the recovery setting. They work very much like a massage by increasing blood flow to depleted areas.

Electrostim machines have gained popularity among professional cyclists who need to recover quickly during multiday races. Special sports versions such as those sold by Compex are effective but expensive. We recommend only using these on the recovery setting. They work very much like a massage by increasing blood flow to depleted areas.

Massage

Massages are another great tool for recovery. A professional massage therapist accustomed to working on athletes can do a better job than self-massage and any machine, which is why pro athletes use them so much.

Final Thoughts on Recovery

Remember: you get weaker during training, and it is during recovery that you become fitter. Equal attention must be paid to each, or your training results will be severely diminished. Using the tools outlined above will help you train more effectively and recover faster. For more information on any of these topics, refer to pages 72–80 in Training for the New Alpinism.