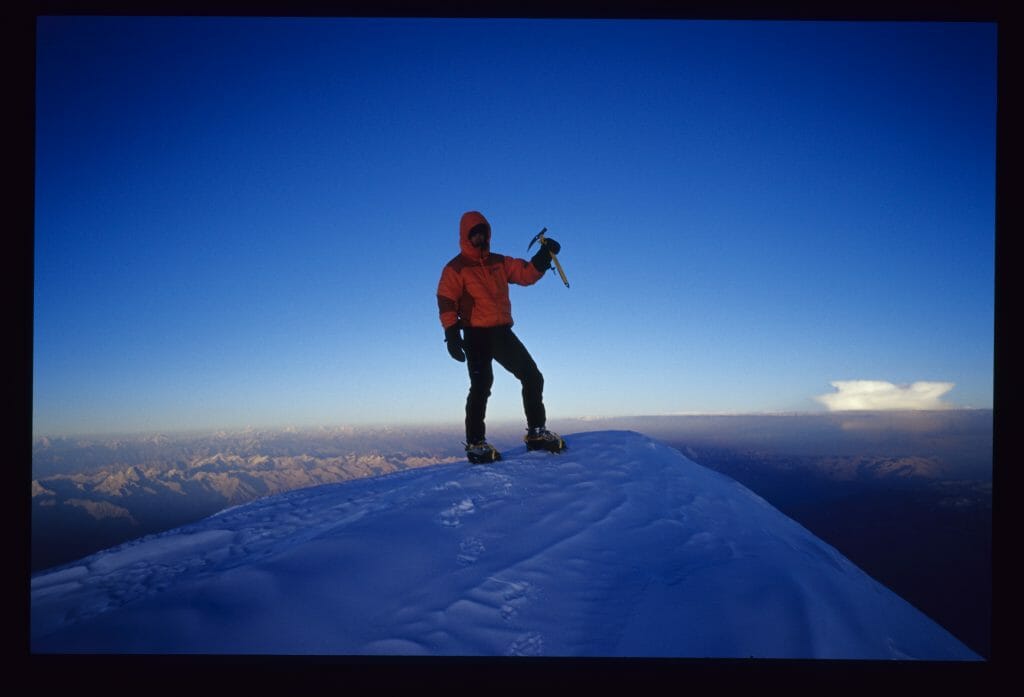

In June 2001, I found myself standing atop the 17,400-foot Mount Foraker in the Alaska Range, looking toward Denali. The Argentine alpinist Rolando Garibotti and I had just climbed the Infinite Spur in 25 hours, turning what was once a multiday testpiece of Alaskan mountaineering into a day climb. Staring at Denali—where I had established three new routes, and climbed the Slovak Direct in a 60-hour push—it dawned on me that there was nothing bigger to climb as far as the eye could see.

At the time Rolo and I made our ascent of the Infinite Spur, there was a cadre of people climbing in the Alaska Range, putting up new routes and going up old routes in this faster and lighter alpine style. Among them was the world-renowned Slovenian alpinist Marko Prezelj.

Hanging out in Base Camp that season, Marko and I had met and we hit it off immediately. Within a few weeks of returning home at the end of that trip, we were scheming to visit the Himalaya. The objective: a new route on the then-unclimbed south face of Nepal’s Nuptse East (25,600 feet/7,802 meters). It would be the biggest mountain I’d ever tried in alpine style. I was nervous, sure—but confident. It couldn’t be that much harder than the Alaska Range … could it?

I trained for the Nuptse climb about the same way I used to train for any expedition. I was ski guiding, climbing one to two days a week, and I spent a lot of time ski touring. A couple months ahead of the trip, I really ramped up my workout routine, doing long climbing days in the mountains plus a lot of Nordic skiing, and just generally pushing myself hard. By the time March rolled around, I felt ready and primed to go.

Near the end of that spring climbing season, Marko, Barry Blanchard, and I found ourselves making good headway on a new route up Nuptse’s south face, to the right of a line established by a joint British-Nepali expedition that had been led by Chris Bonington in 1961. We were climbing well together; the team felt strong. The weather wasn’t absolutely perfect, but our window was holding. On the third day, we got to a high camp—what we suspected to be our last bivy—and were within reasonable striking distance of the summit of Nuptse East. Barry had worn himself out and announced that he’d take on a support role while Marko and I made the final push for the unclimbed summit. But when Marko and I left the tent that morning for the summit, I simply hit a wall. Everything felt difficult, even relatively simple terrain. Marko, on the other hand, was ready and raring to go. He was just so much stronger than I was. It was cold, and it wasn’t a perfect day, to be sure—but the fact of the matter is two Marko Prezeljs could have summited that day. But one Marko and one Steve could not, owing largely to my lack of fitness. It became clear that I didn’t have what it took to continue, so we turned around and went down.

This was to be the biggest wake-up call of my life as a professional climber. Without trying to sound arrogant, just to be perfectly matter of fact, I think Marko was the first partner I teamed up with who was head and shoulders better than I was—especially in terms of fitness. I wasn’t only frustrated to have narrowly missed such an incredible opportunity to summit an unclimbed peak; I was also embarrassed at having failed my partner. I made up my mind to start training in earnest as soon as I got home. Fortunately, Marko didn’t hold it against me too much. On the way out, we were already making plans to return the following year to attempt an incredible (and still unclimbed) line on Masherbrum in the Pakistani Karakoram.

When I got home to Mazama, in Washington, I happened to find myself among a small but vibrant group of very talented Nordic skiers and Nordic ski trainers. I knew I would need professional help to achieve the kind of fitness I was aiming for, so I solicited from that group a woman who was a former assistant coach for the Canadian women’s Olympic XC skiing team.

She and I talked briefly about my goals, and where I was at currently, and then she wrote out a few months of workouts for me. What neither of us really took into account was my life outside the training. All winter long, I worked as a helicopter ski guide out of Mazama. I’d have to be at work at 7:00 a.m., so each day I’d get up long before the sunrise and do my workout at 4 or 5 in the morning. Then I’d go to work and guide 10,000 feet of powder descents each day (the minimum guarantee of the company; some days we’d ski 30,000 feet), all while wearing a 30-to-40-pound guide’s pack. On my days off, I would go on long ski tours, continue the training program, tackle alpine climbs—anything but rest.

I did that all winter until, sometime in the middle of February, I became sick in a way I had never experienced before. I was basically in bed for a month, completely laid up. I couldn’t move and the docs had me on an IV, taking antiviral and antibiotic drugs, the whole nine yards. To be honest, it was a major struggle to get up and go to the bathroom. They never figured out exactly what I had; they just called it an unknown viral infection, and left it at that.

Of course, I understand now what happened. I overtrained. Between work, training, the harsh weather, the lack of sleep, and just going nonstop for months, I forced my body into shutdown mode. Two months after getting sick, when I was hoping to be in the best shape of my life, I went for a ski tour to test the waters. I decided to do a small tour that normally would have taken me an hour of ascent. This time, it took me 4 hours. I was completely distraught.

I still ended up heading to Pakistan with Marko and another Slovenian alpinist, Matic Jost, in the middle of May. This in spite of the fact that I wasn’t fully recovered from the illness. Through being bedridden and stressed and everything else, I’d lost any and all conditioning I’d gained. It ended up being something of a moot point, as we never got enough good weather to make a serious bid at the objective. But when I came home, I knew I wanted to train again—there was no question about that. The question was how.

When I returned to Mazama again, I started casting about for help and ideas. I talked to other coaches and I began reading more about the theories of and it quickly became clear that I needed to understand how the aerobic system works, how to establish a base of fitness, how to incorporate organized rest and peak workouts into my training regime, and how to plan a strength program.

The year that coincided with my first full year of training with Scott was one of the best climbing years of my life. Marko and I climbed the North Face of North Twin in the Canadian Rockies, and then I returned to the Karakoram and soloed a new route on K7 and attempted Nanga Parbat by a new route on the Rupal Face. For those several months I was in amazing shape, and I felt utterly unstoppable.

The big key to my training with Scott was to shift my focus away from technical climbing and toward building my capacity for physical work. By that time, as Scott Johnston had pointed out, my technical climbing skills were “good enough” for the situations I was going to encounter on these big mountain routes. My capacity for the kinds of physical beatings that your body is subjected to on huge alpine climbing days, however, was lacking. That was where I had the most room for improvement, so that is where we focused. It was a total sea change for me, as I was of the old school of thought that “the best way to train for climbing is to go climbing.” As it turned out, that couldn’t have been farther from the truth for my situation.

After my first season I was a total believer. It was amazing. The next year, in 2005, Vince Anderson and I climbed a new route on the Central Pillar of the Rupal Face on Nanga Parbat. In 2006, we got super close (like within a couple hundred feet) of the 7,821-meter summit of Kunyang Chish East, eventually getting shut down by really bad snow conditions on the summit ridge. In 2007, I climbed a new route on K7 West, and a number of smaller new routes in the Karakoram. The year after that, I attempted Makalu, and did a very hard new route on Mount Alberta in the Canadian Rockies; the two parties to repeat our line (or a variation to it) resorted to aid climbing where I free climbed. These years that I spent working hand in hand with Scott Johnston became the most successful climbing years of my life.

During that time (and I think Marko and Vince and others would agree), I was in the best shape of any climbing partner I roped up with. I’m not trying to brag—but I want to make one simple point: the training worked. It had completely transformed me, and my climbing abilities. What I came to realize is that every alpine climb comes down to at least one moment where you’re just not sure if you can continue. And in those moments, it’s absolutely crucial that you have enough energy, fitness, focus, and gas in the tank to say, “Yes, I can keep going.”

I was at the height of my climbing career when, in 2010, I had a really bad accident on Mount Temple. While the illness I suffered through back in 2002 had invalided me for a few months, it was immediately apparent that this fall (from which I barely escaped with my life) would set me back for years.

It was during this time that Scott Johnston and I decided to write what would become Training for the New Alpinism and The New Alpinism Training Log. It was partially that Scott, just being a friend, saw that I would need something to keep me busy during my convalescence. But it was also that we believed we had a unique view on this world of training for alpinism, which we wanted to share with our friends and extended communities.

We both knew plenty of people who thought of training, like I had, as basically climbing a lot, and then going balls to the wall for a couple months before an expedition. When we discovered a model that was so much more efficient and effective, it was only natural that we would want to share it. So we set out to write this book—a colossal task in and of itself.

Since the book has been published we’ve received dozens if not hundreds of emails from people thanking us for helping them to achieve their alpine goals. From climbing Everest without supplemental oxygen, to establishing new technical routes in the most remote ranges in the world, to training for trekking in the Khumbu, to climbing Mount Hood, to competing in ultra-distance footraces—all kinds of people with all kinds of backgrounds have successfully used the principles described in Training for the New Alpinism to help them achieve their mountain dreams.

Since becoming a father, and letting my life shift more toward raising a family than conquering remote peaks, I’ve become increasingly focused on helping others improve their own long-term fitness for alpine climbing. That is why we have created this website, everyone at uphill athlete is so deeply invested in our work as coaches and mentors.

The fact is, there is no magic key to help you open the door of endurance training. There are no six simple steps you can follow, no guru who can take you there, and no diet that can turn you into Ueli Steck. There are, however, 100 years of history and a well-understood intellectual framework behind the theories and techniques that apply to the full spectrum of endurance sports. Today our mission is to train, teach, and connect all mountain athletes. We hope you learn something, but, above all, we hope you will go outside and apply what you learn to the goals and dreams that brought you here in the first place.