When I was young I discovered climbing, through my parents. I was fascinated by the big world of mountains from day one. I can’t say I ever made a conscious decision to become a climber; I followed a path of fascination that developed into a love. Thirty years on and I’m still climbing and I still love it and I still create new, interesting adventures. Thankfully, I’ve also become a coach via the platform of Uphill Athlete. Besides the balance and strategy of creating workouts to mold an athlete to be her best, what most fascinates me about coaching are my athletes’ motivations. This includes what brings them to Uphill Athlete in the first place and what drives them to develop themselves as athletes, and as human beings.

Broadly speaking I have three types of athletes:

- Those who always complete their workouts with little to no prompting from me.

- Those who occasionally miss a workout and need an occasional nudge of encouragement. This is the majority, by far.

- Those who consistently miss workouts. These athletes are always stressed and distressed by the fact of a newly missed workout and they seem to suffer from their struggle to get workouts done.

All frequent readers of this website and our books know that consistency, getting those five to six workouts per week done to the best of one’s ability, is the first principle of successful endurance training. If that is understood, why is it hard to translate that understanding into action? Why do some people get their workouts done easily while others struggle week in and week out, and torture themselves about it to boot?

Getting to Consistency in Training

To emphasize the principle of consistency in training, I often repeat my sand wall analogy to new athletes signing up for coaching. No one workout will make you fit, so imagine each workout is a single brick made of highly compressed sand. Each day you have the opportunity to lay one brick. Not two or three, but one brick per day. If you miss a workout, you lay zero bricks. Eventually if you are consistent with your bricklaying workouts you will build a wall, and if you continue long enough, without missing workouts and you stay healthy and get adequate recovery, you’ll build a house of fitness. The house is ultimately made of sand, so it won’t stand long without continually re-laying the bricks that erode with time. But it is possible to build and maintain a strong house of fitness for a very long time, even decades.

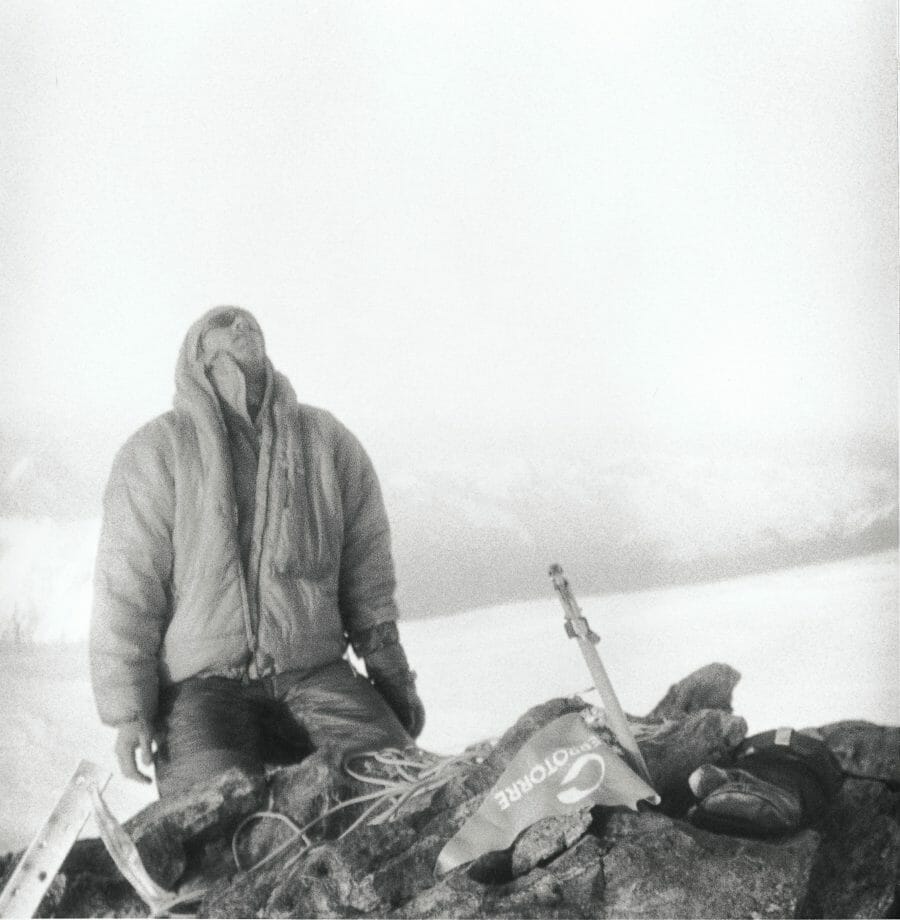

A great climb has all the components of a good story: a worthy goal, commitment, crises, effort, and resolution. Some stories end with a summit, some with the approach, some with a storm, some with death. The conclusion is unforeseeable, the lessons hard-won and costly. The unanswerable question—why climb—becomes all the more intriguing and begs us another question: What is success?

…Action is the message. Success is found in the process.

From the Epilogue of my 2009 book, Beyond the Mountain

In our day and age, more than perhaps at any other time in human history, people are chasing success, satisfaction, happiness … outcomes. As I learned through the process of preparing for and eventually climbing the Rupal Face of Nanga Parbat and numerous other climbs, the outcome itself is empty.

This is not something I learned quickly, or easily. In the height of my professional climbing career I dreaded, even mocked, the inevitable journalist would would ask me “What’s next?” I didn’t like to talk about my climbing goals and objectives publicly; it always felt like such public planning teetered precariously close to bravado. I would, as a rule, talk about what I had done, but not about what I planned to do.

In hindsight this may have been a mistake. This is typically the time of year we reevaluate our plans and set out goals, and establish process goals. This year I want to propose another way.

Focus on the Chase

We are physiologically designed for the process. We are rewarded by feel-good dopamine when engaged in the chase. The catch is simply the conclusion and the end of the dopamine reward. Perhaps this is a remnant of our hunter-gather past, that we had to be incentivized to hunt up food.

In climbing, when we climb, or chase, we feel good, but then we are met with a depressing letdown and feeling of discontentment when we finally reach the summit or clip the chains. The reward of the summit never meets our preconceived expectations and we are left with “What now?”

To not have another idea—another peak, another race, another adventure—on hand as soon as one adventure is complete is a mistake. The process of the chase should renew almost as soon as you’ve recovered, mentally and physically, from the last climb/race/ski. Remember: The chase, the process, that is to say the dopamine, drives us forward.

Reimagine your workouts as the chase, and the big climb, the long run, the fast ski as simply a pause, perhaps a highlight, but no more than part of the overall process of being a lifelong athlete. Understand what you’re doing in your training, and why. (That’s why we are here!)

A common mistake I see athletes making is they set unrealistic, far-off goals. Everest shouldn’t be your first mountain. You should climb it as one of hundreds if not thousands of ascents, and if you do so I wager that you will come to value them all equally. You shouldn’t run a 100-miler having never run a 50-miler. Technically difficult climbing has a nice built-in regulator: the technical climbing itself takes years to learn and develop, so no one is going to climb the North Face of the Eiger as their first-ever ice climb.

Society (and social media) leads us to think we always need to plant a flag. To “succeed.” To accomplish the goal, take the job, publish the book, get the degree. And if we don’t, we’re screwed.

Part of my own philosophy of climbing is that the climbs that we accomplish are simply manifestations of what we could already do. The training is where the real work of improvement, and the possibility of future success, is created. The climbs in our careers that we fail on are the ones that truly demonstrate the upper limits of our abilities because they take us right up to that limit.

Make Better Decisions

The day you say you have to do something, you’re screwed. —Moneyball

Bad decisions are made—and workouts are missed and summits are not climbed and races are not run—when we put stress on ourselves and back ourselves into a corner. This is how athlete #3, the one who misses workouts, and agonizes about them, is functioning. These are the athletes who won’t be maximally successful. They need to shift the way they make decisions, and as their coach, it’s my job to help them.

Here is what I wrote to one such athlete:

“When you put off a workout to the end of the day, you then feel forced to do the workout and you put intense pressure on yourself. And while pressure often is considered advantageous, your stress hormones will stick around at higher levels for a longer period of time since you put off starting the workout, and nearly didn’t get it done. This chronic stress of feeling pressured further shifts how you are going to make decisions in other areas of life. If you’re interested, have a read through this article on stress

“Missing these workouts, I suspect, is a manifestation of how you make decisions in other parts of your life. Though you’ve obviously been successful in many ways, I would like you to reflect on what I’ve suggested. Feel free to tell me I’m off-base here, but I suspect that if we can solve this issue with your workouts that we can re-wire your brain to make better decisions in many aspects of life and these workouts, and your upcoming expedition, will be the life-affirming and life-changing experience that you want to have, that I believe you are here to have.”

To learn is to change. —George Leonard

Avoid Overplanning

One thing I learned from expedition climbing was to meticulously control everything that was within my control. There were plenty of things, especially weather and conditions, that were far beyond my control. In Pakistan, which is majority Muslim, people are fond of saying “Inshallah,” God Willing, whenever any obstacle is met. I originally found this incredibly annoying, thinking that god, whose existence I doubted in the first place, had any interest in giving me seven days of clear weather so I could attempt to climb a random icy peak. Over time, and some journaling, I came to understand Inshallah as a way to shift responsibility away from oneself and onto another being, real or imaginary. And this new viewpoint helped me realize that I could work hard, control what was controllable (like my preparations), and let go of the rest. Whether that be to an omnipotent being or the randomness of weather patterns. This same sentiment is manifested in a simple shrug of the shoulders.

This attitude, in turn, taught me or made me more aware that while I should work hard, it is absolutely imperative that I truly enjoy that work. This final realization, the pleasure in the daily work, looking forward to each and every opportunity to improve, was key to allowing my own type A personality to let go of the outcome being a success or failure.

Success or failure became getting my daily workout done. I focused on consistency in training. I realized that if I maximized my daily opportunity to improve, that the final outcome would take care of itself. After all, good weather also happens and there are days when the mountains open up and conditions come together and success is a summit, and we are able to physically manifest what we as climbers can do.

Which brings me to the ultimate point I want to make at the start of this year. One can plan. Indeed, many of our athletes can and do overplan. But if you plan relentlessly, and hold on to the outcome alone as proof of your own success, failure, or (worse) personal value, then you are doomed to suck. There is simply too much that we can never control, and so it’s only a matter of time before you invest a lot, control everything you can, and fail miserably.

Love the Process

The key to consistency in training is not in the Inshallah per se. It is found in the dopamine, in truly loving the process. Loving it so much that you embrace every opportunity to improve and move forward toward your chosen goal. Every opportunity to either train or recover, to study your sport, to improve yourself in your chosen way. You not only take it, you seize it. Once you get to that point, where you love the process of working hard at something you enjoy, eventually things will come together and your climb will be realized. Though perhaps not according to your (overplanned) schedule.

Climbing a difficult new route like the Anderson-House on the Rupal Face, given perfect preparation, has about a 10 percent chance of success. If I factor in all the other expeditions I made to routes of that same scale (Makalu, Khunyang Chhish, Masherbrum), I think the 1 in 10 holds up pretty well for climbs of this scale and difficulty. But it’s still 10 percent odds, not 1 percent or 0. And eventually it worked out.

If each athlete we at Uphill Athlete touch can learn to avoid the rat race of chasing success, satisfaction, happiness, and an egregiously idealized outcome and instead engage the simple, evolutionarily programmed mechanism of dopamine reward that is designed to keep us engaged in the hunt, those athletes will be successful. We will have been successful.

Strive for a Lifelong Practice

We are ingrained with an internal bias, termed the teleological fallacy, that gives us “the illusion that you know exactly where you are going, and that you knew exactly where you were going in the past, and that others have succeeded in the past by knowing where they are going.” This creates a false sense that you need to establish, and know, your direction in order to be successful. It also creates the idea that others who were successful knew exactly where they were going. Both are wrong.

Mastery comes from the habit of learning. Learning changes us, as George Leonard powerfully argues in his book Mastery. To truly learn means that we create, consciously and purposefully, new habits and new routines that move us toward our better selves. This strategy is not limited to athletics. Indeed, your success lies is in the process of the lifelong practice of your sport, and your sport becomes a crucible for all of life, not just the summits or the finish lines.

Your path then is simple: Focus on and prioritize the daily process of training. The practice. Strive for consistency in training. Work hard at arriving at base camp or your starting line as well prepared as you can be. See those trips, runs, skis, climbs as part of a process, and you will come to value each of them individually, and the whole more greatly. The secret? If you do all of this, the outcomes will come. Indeed: Action is the message. Success is found in the process.

-by Uphill Athlete co-founder Steve House